The largest and one of the oldest mosques in the city of Aleppo, Syria, is the Great Mosque of Aleppo, also known as the Umayyad Mosque (Arabic: جَـامِـع حَـلَـب الْـكَـبِـيْـر, Jāmi‘ Ḥalab al-Kabīr). During the reign of Umayyad Caliph al-Walid I ibn ‘Abd al-Malik (r. 705-715/86-96 AH) or his successor, Sulayman (r. 715-717/96-99 AH), the mosque was first built in the heart of the old city of Aleppo. It is situated in the Ancient City of Aleppo district of al-Jalloum, a World Heritage Site, near the entrance to Al-Madina Souq. The mosque is allegedly home to the remains of Zechariah, John the Baptist’s father, both of whom are revered in Islam and Christianity. During the recent Syrian War, the Great Umayyad Mosque in Aleppo, originally founded by the first imperial Islamic dynasty and currently part of a UNESCO World Heritage Site, once again stood as a battlefield, but this time it lost its most powerful and resilient feature, the Seljuk Minaret of the 11th century.

On the site of the former Roman temple and Byzantine cathedral built by St. Helen (mother of Constantine the Great), the Great Mosque, or Umayyad Mosque of Aleppo, was built. The mosque was founded by the Umayyad Caliph al Walid in 715 and completed by his successor Caliph Suleiman. The mosque has always been the center of the battlefield during all invasions. The Crusaders, the Fatimids, the Ayyubids, the Mongols, and the Mamluks all engaged in the demolition and eventual restoration of the mosque. Historian of Architecture K. A. C. Creswell attributes its construction solely to the latter, quoting 13th century Aleppine historian Ibn al-Adim who wrote Sulayman’s intent was “to make it equal to the work of his brother al-Walid in the Great Mosque at Damascus.” Al-Walid built the mosque using materials from the so-called “Church of Cyrrus”, another tradition says.

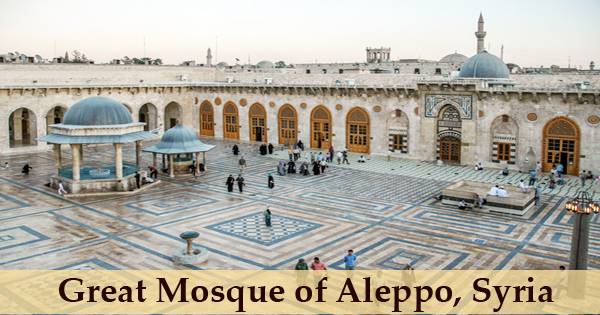

Great Mosque of Aleppo, Syria

The Abbasids, who vandalized the mosque and looted its ornaments and artwork as revenge against the Umayyads, were the first tragedy to hit the mosque. The mosaics and ornaments were destroyed by a Byzantine emperor, according to other historians, when he conquered the city and burned the mosque to the ground. The building has undergone numerous repairs and reconstructions throughout its history in response to natural disasters (earthquakes and fires) and to alter its use, resulting in the growth of its surroundings. After a great fire, Nur al Din rebuilt it in 1169 and the mosque was destroyed again during the 1260 Mongol invasion.

In 1090 AD, only for another dynasty to conquer the city and ruin the mosque, the Seljuks restored the mosque and constructed the distinguished minaret, leaving only the minaret intact. After the extension of the plan made by Nour Al-Dine Zangi in 1158 AD, the Muslim commander who fought the Cursaders, the mosque’s plan was finalized. Architectural historian Jere L. Bacharach, however, writes that Maslamah ibn Abd al-Malik, a brother of al-Walid and Sulayman who served as governor of the local province (Jund Qinnasrin) sometime before 710 until at least the early period of Sulayman’s rule, was the most probable patron of the mosque.

The mosque remains an iconic Islamic landmark, despite of all the structural modifications. The completed design of the plan (following the reconstruction of Zangi) was arranged in a rectangular 150 × 100-meter hypostyle pattern. In the centre, there is a wide marbled courtyard with pavilions, fountains, porticoes and gates that provide access to the mosque from all sides (the eastern gate, however, can provide prayers with direct access to the praying hall). The Mirdasids governed Aleppo in the second half of the 11th century and constructed a single-domeed fountain in the courtyard of the mosque. The 45-meter-high minaret was built at the northwest corner of the mosque by the Shia Muslim qadi (‘Chief Islamic Judge’) of Aleppo, Abu’l Hasan Muhammad, in 1090, during the reign of Selyuk Governor Aq Sunqur al-Hajib. During the rule of Tutush, its building was completed in 1094. Hasan Ibn Mufarraj al-Sarmini was the architect of the project.

Three wide aisles, divided by a series of colonnades, all parallel to the Qibla wall, form the prayer hall. Within that wall, in its middle, a yellow-stoned Mihrab is pierced, directing visitors to the path of prayer. Qalawun’s renovations, along with a central dome in front of the Mihrab, replaced the originally-flat ceiling with a cross-vault structure. An ornamented Maqsurah (enclosed space) which holds the tomb of the remains of Prophet Zakariya sits alongside the Mihrab. A lavish robe, embroidered with silver-colored Quranic verses, drapes the tomb. After a great fire that had destroyed the earlier Ummayad building, the mosque was rebuilt and enlarged by the Zengid sultan Nur al-Din in 1159; in 1260, the Mongols razed the mosque.

Recently (2003-04), the Great Mosque of Aleppo underwent extensive reconstruction, during which the courtyard and the minaret were especially restored. Maybe the most prominent feature of the mosque is the Minaret, which has been standing since the 11th century on the southern side of the building. Several historians say that, in order to construct the foundations of the minaret, engineers had to dig deep enough to reach the water. With metal braces, the base was reinforced, supporting the 50-meter frame. As for the ornamentation, the minaret was covered with moldings of Kufic and Naskhi scripts and calligraphic bandeaus. The mosque was badly damaged during clashes between Free Syrian Army armed groups and Syrian Army forces on 13 October 2012. A presidential decree was issued by President Bashar al-Assad to form a committee to rebuild the mosque by the end of 2013.

The main prayer hall is the shrine of Zachariah (father of John the Baptist), a wood-carved minbar (pulpit) from the 15th century, and an elaborately carved mihrab (niche indicating the direction of Mecca). The remaining sides of the courtyard are occupied by three more halls. Each of the eastern and northern halls has two naves, while there is one in the western hall. The latter is more industrial architecture. The east hall dates to the time of Malik Shah (1072–92) and the north hall was renovated during Mamluk sultan Barquq’s reign (1382–1399), but largely retained its original 11th century character. The building represents the ancient past and layered history of Aleppo itself: today’s mosque does not maintain its original shape, having undergone a number of renovations and reconstructions in its continuous use for over a thousand years.

Mosque in 2013, after the destruction of the minaret

The Great Mosque has a small museum containing a number of ancient manuscripts attached to it. Similar to the Great Mosque of Damascus, a maqsurah was constructed in the form of a square domed room raised by one step above the floor level of the prayer hall and decorated with Kashan tiles that cover all the internal surfaces of its walls. The entrances to the maqsurah include a wide arched gate supported by two strong columns and topped with capitals and a bronze door screen. The recently demolished minaret of the mosque captured the attention of many scholars who give interpretations of its unique historical and aesthetic importance. In the early Islamic culture, Terry Allen, who researched the development of architecture and decoration, saw the minaret as an example of a conscious revival of local late antique architectural ideas in northern Syria, exemplified in the architect’s use of classifying elements such as moldings, blind arches, and bands of inscription.

Information Sources: