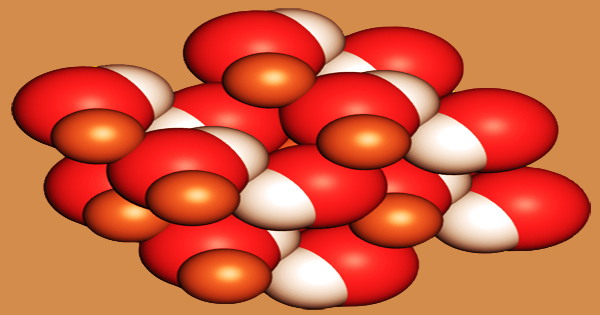

The inorganic compound ferrous hydroxide, often known as Iron(II) hydroxide, has the formula Fe(OH)2. When iron(II) salts, such as iron(II) sulfate, are reacted with hydroxide ions, it is formed. Transition metal hydroxides are a class of inorganic chemicals that include this substance. These are inorganic compounds with hydroxide as the biggest oxoanion and a transition metal as the heaviest atom not in an oxoanion.

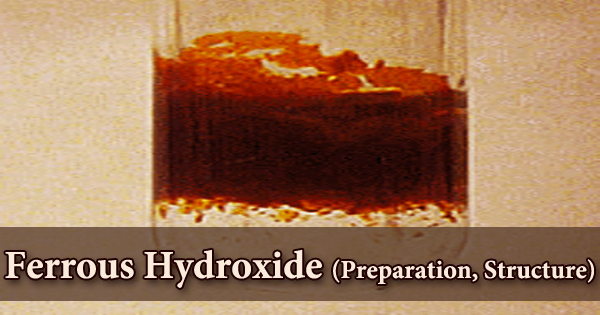

Pale green hexagonal crystals (when partially oxidized) or white amorphous powder (when pure); density 3.4g/cm3; decomposes on heating; insoluble in water (1.5 mg/L at 20°C), KSP 8.0 x 10-16; soluble in acids; moderately soluble in ammonium salt solutions; insoluble in alkalies Iron(II) hydroxide is a white solid with a greenish tint due to residues of oxygen. “Green rust” is a term for the air-oxidized solid. In water, iron(II) hydroxide is weakly soluble (1.43 × 10−3 g/L, or 1.59 × 10−5 mol/L). It forms as a result of the reaction between iron(II) and hydroxide salts.:

FeSO4 + 2NaOH → Fe(OH)2 + Na2SO4

The precipitate can range in color from green to reddish brown depending on the iron(III) concentration if the solution is not deoxygenated and the iron is not reduced. Iron(II) ions are quickly replaced by iron(III) ions generated by the oxidation of iron(II). If the crystal development conditions are inadequately regulated, it can also form as a by-product of other processes, such as the production of siderite, an iron carbonate (FeCO3).

When iron(II) salts are treated with alkali in an airless environment, ferrous hydroxide forms as a white flocculent precipitate. In the presence of air, it darkens fast to a dark green, then to an almost black color; at this point, the precipitate contains both iron(II) and iron(III). Green rust is a new mineralogical type that has recently been identified. The ideal iron(II) hydroxide compound is more complicated and changeable than all forms of green rust (including fougerite).

The red-brown iron(III) hydrous oxide is produced when there is an excess of oxygen. Iron(II) hydroxide is incompletely precipitated by ammonia due to the production of iron(II) ammonia complexes, at least in part. Iron(II) hydroxide may be oxidized by water protons to generate magnetite (iron(II,III) oxide) and molecular hydrogen under anaerobic circumstances. The Schikorr reaction describes this process:

3 Fe(OH)2 → Fe3O4 + H2 + 2 H2O

Selenite and selenate anions may easily bind to the positively charged surface of iron(II) hydroxide, where they are then reduced by Fe2+. The resultant products have a low water solubility (Se0, FeSe, or FeSe2). In the absence of air, ferrous hydroxide can be made by precipitating an iron(II) salt solution with caustic soda or caustic potash. The substance is utilized in abrasives as well as pharmaceuticals.

Iron(II) hydroxide has also been looked into as a means of removing harmful selenate and selenite ions from water systems like wetlands. These ions are reduced to elemental selenium by the iron(II) hydroxide, which is insoluble in water and precipitates out. Iron(II) hydroxide is the electrochemically active substance of the nickel-iron battery’s negative electrode in a basic solution.

Reduced iron II is the form of iron dissolved in groundwater. Iron II is oxidized to iron III and forms insoluble hydroxides in water when this groundwater comes into contact with oxygen at the surface, such as in natural springs. The exceedingly uncommon mineral amakinite, (Fe,Mg)(OH)2, is the natural counterpart of iron(II) hydroxide compound.

Information Sources: