Endogenous viral elements ((EVEs) are remnants of ancient viral infections that have become ingrained in the genome of an organism. EVE is a virus-derived DNA sequence found in the germline of a non-viral organism. These viral elements are essentially viral DNA fragments that have been integrated into the host organism’s germ line cells and are thus passed down from generation to generation.

EVEs can be entire viral genomes or viral genome fragments. They form when a viral DNA sequence is integrated into the genome of a germ cell, which then produces a viable organism. The newly established EVE can be passed down from generation to generation as an allele in the host species and may even achieve fixation.

Throughout evolution, organisms, including humans, have been exposed to a variety of viruses. When the immune system fails to eliminate a virus, the viral genetic material can become integrated into the host genome. This integration can take place in the DNA of germ cells (sperm or egg cells), and as a result, the viral DNA is passed down to the offspring.

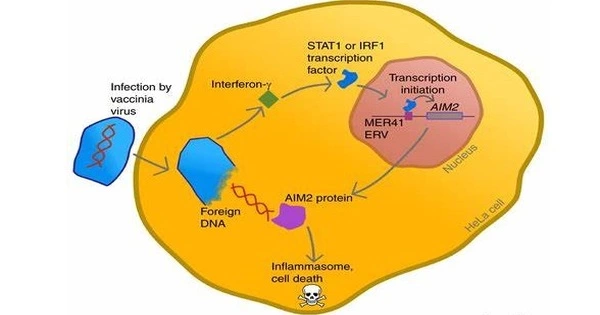

Endogenous retroviruses and other EVEs that exist as proviruses have the potential to produce infectious virus in their endogenous state. The replication of such ‘active’ endogenous viruses can result in the spread of viral insertions in the germline. Germline integration appears to be a rare, anomalous event for most non-retroviral viruses, and the resulting EVEs are frequently only fragments of the parent virus genome. Such fragments are usually not capable of producing infectious virus, but may express protein or RNA and even cell surface receptors.

Endogenous retroviruses (ERVs) are a type of endogenous viral element that is common. Retroviruses are RNA viruses that can reverse transcribe their RNA genome into DNA before integrating this DNA copy into the host genome. When viral genetic material is integrated in germ line cells, it becomes a permanent part of the host species’ genetic makeup.

Endogenous viral elements research sheds light on long-term interactions between viruses and their hosts throughout evolutionary history. While some endogenous viral elements have been linked to diseases, many appear to be harmless and have even been co-opted by the host organism for beneficial functions over time.

In humans, for example, remnants of ancient retroviral infections make up a significant portion of the genome. Despite their viral origins, the majority of these endogenous viral elements are now thought to be non-functional and are commonly referred to as “fossil” or “junk” DNA. Some may still play functional roles or influence the regulation of nearby genes. Endogenous viral elements research helps us better understand the complex interplay between viruses and their hosts over evolutionary timescales.