The exhilaration of racing down Rainbow Road, squeaking around a curve, and grabbing a power-up from one of the floating square icons on the screen is well known to Mario Kart fans. Less preferable, though, is to slip on a banana peel laid by another racer and fly off the side of the road into oblivion.

One of the things that makes the iconic Nintendo racing game, which has been around since the early 1990s, so fascinating is this intense battle between many players, who employ a range of game tokens and equipment to accelerate ahead or impede their rivals.

“It’s been fun since I was a kid, it’s fun for my kids, in part because anyone can play it,” says Andrew Bell, a Boston University College of Arts & Sciences assistant professor of earth and environment. But as a researcher studying economic principles, Bell also sees Mario Kart as much more than just a racing game.

In a recent paper, Bell makes the case that the principles of Mario Kart, particularly those elements that make the game so addicting and enjoyable for players, can act as a useful framework for developing more equitable social and economic programs that would better support farmers in underdeveloped, rural areas.

That’s because the game is made to keep you in the race even when you’re performing terribly, like flying over the side of Rainbow Road in Mario Kart.

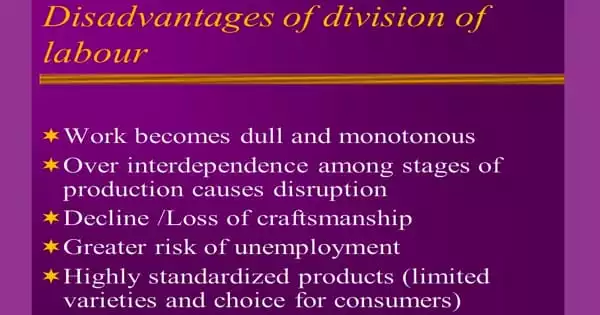

“Farming is an awful thing to have to do if you don’t want to be a farmer,” Bell says. “You have to be an entrepreneur, you have to be an agronomist, put in a bunch of labor, and in so many parts of the world people are farmers because their parents are farmers and those are the assets and options they had.”

This is a typical tale Bell has encountered often when conducting research in Pakistan, Bangladesh, Cambodia, Malawi, and other southern African nations, and it is partly what motivated him to concentrate his study on public policies that could promote development.

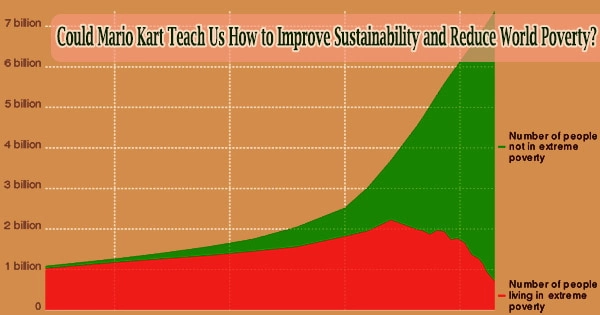

In recent research, Bell makes the case that policies that directly support farmers in the world’s poorest developing nations could contribute to both an overall decrease in poverty and an increase in environmentally benign and sustainable practices.

Farming is an awful thing to have to do if you don’t want to be a farmer. You have to be an entrepreneur, you have to be an agronomist, put in a bunch of labor, and in so many parts of the world people are farmers because their parents are farmers and those are the assets and options they had.

Andrew Bell

According to Bell, the concept is similar to how Mario Kart provides players who are falling behind in the race the best power-ups in order to push them to the front of the pack and keep them in the race.

At contrast, speedier players in the front usually receive inferior abilities, such as ink splats or banana peels to interfere with the other players’ screens, rather than these similar enhancements. Bell claims that this strategy, known as “rubber banding,” is what keeps the game exciting and engaging because there is always a chance for you to win.

“And that’s exactly what we want to do in development,” he says. “And it is really, really difficult to do.”

Rubber banding is easy in the world of video games because there aren’t any obstacles from the outside world. Rubber banding, however, to provide financial resources to agricultural families and communities, who need them the most, is a very complex idea in the actual world.

These possibilities could take the form of the following, according to Bell: Governments could set up a program where a third party, such as a hydropower company, would pay farmers to adopt agricultural practices that would help prevent erosion in order for the company to build a dam to generate electricity.

According to Bell, it is a complex transaction that has only been successful under very precise conditions, but systems like this one, called Payments for Ecosystem Services (PES), have proven effective in assisting both farmers and the environment.

Finding private businesses that are prepared to pay for ecosystem services and linking them with farmers who are open to changing their agricultural practices is a significant difficulty. The good news about rubber bands, however, is that as more people engage in such economic initiatives, more others will do the same, a phenomenon Bell refers to in his study as “crowding in.”

The largest challenge, according to Bell, is figuring out how to get help to those in need in the first place because, until recently, many of the population was virtually living off the grid.

“It’s hard to know who is in the back of the pack,” Bell says.

But according to Bell, in the past ten years or so, communication with those living in low-resource areas has become easier, partly as a result of the widespread use of mobile phones. (In another recent paper, Bell and his collaborators found that smartphones can also play a role in understanding and addressing food insecurity.)

Currently, mobile devices assist local governments and groups in identifying those looking for more affluent means of subsistence outside of the difficult practice of agriculture and in connecting with those individuals with economic prospects.

According to Bell, increasing the availability of mobile devices in underdeveloped areas of the world would also make it possible to more accurately evaluate the wealth gap between the richest and poorest families and assess the efficacy of recently put into placed policies and initiatives.

“Mario Kart’s rubber-banding ethos is to target those in the back with the items that best help them to close their gap their own ‘golden mushrooms,’” Bell wrote in the paper, referring to the power-up that gives lagging racers powerful speed bursts.

Researchers and decision-makers must initially evaluate “what the golden mushroom may be within their unique context and problem at-large” in order to enhance environmental stewardship while reducing poverty.