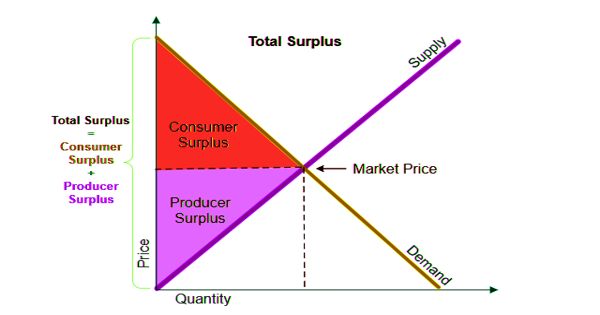

Consumer surplus – the difference between consumers pay and willingness to pay

Consumer surplus is the difference between the maximum price a consumer is willing to pay and the actual price they do pay. In competitive markets, firms have to keep prices relatively low, enabling consumers to gain consumer surplus. It happens when the price that consumers pay for a product or service is less than the price they’re willing to pay. If a consumer is willing to pay more for a unit of a good than the current asking price, they are getting more benefit from the purchased product than they would if the price was their maximum willingness to pay. It is an economic measurement of consumer benefits. They are receiving the same benefit, the obtainment of the good, with a smaller cost as they are spending less than they would if they were charged their maximum willingness to pay. If markets were not competitive, the consumer surplus would be less and there would be greater inequality.

Consumer surplus is an economic measurement of consumer benefits. It enables consumers to purchase a wider choice of goods.

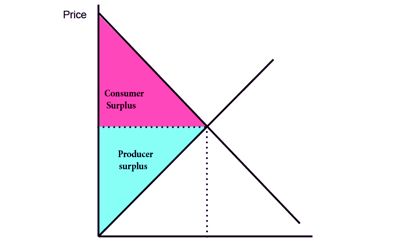

Consumer surplus enables consumers to purchase a wider choice of goods. An example of a good with a generally high consumer surplus is drinking water. People would pay very high prices for drinking water, as they need it to survive. The difference in the price that they would pay, if they had to, and the amount that they pay now is their consumer surplus. The utility of the first few liters of drinking water is very high (as it prevents death), so the first few liters would likely have more consumer surplus than subsequent liters. On a supply and demand curve, it is the area between the equilibrium price and the demand curve.

It’s a measure of the additional benefit that consumers receive because they’re paying less for something than what they were willing to pay. The maximum amount a consumer would be willing to pay for a given quantity of a good is the sum of the maximum price they would pay for the first unit, the (lower) maximum price they would be willing to pay for the second unit, etc. It can be calculated on either an individual or aggregate basis, depending on if the demand curve is individual or aggregated. Typically these prices are decreasing; they are given by the individual demand curve, which must be generated by a rational consumer who maximizes utility subject to a budget constraint. Consumer surplus always increases as the price of a good falls and decreases as the price of a good rise. Because the demand curve is downward sloping, there is diminishing marginal utility.

Diminishing marginal utility means a person receives less additional utility from an additional unit. However, the price of a product is constant for every unit at the equilibrium price. It is based on the economic theory of marginal utility, which is the additional satisfaction a consumer gains from one more unit of a good or service. The extra money someone would be willing to pay for the number units of a product less than the equilibrium quantity and at a higher price than the equilibrium price for each of these quantities is the benefit they receive from purchasing these quantities. The utility a good or service provides varies from individual to individual based on their personal preference.

For a given price the consumer buys the amount for which the consumer surplus is highest. The consumer’s surplus is highest at the largest number of units for which, even for the last unit, the maximum willingness to pay is not below the market price. It has been an important tool in the field of welfare economics and the formulation of tax policies by governments.