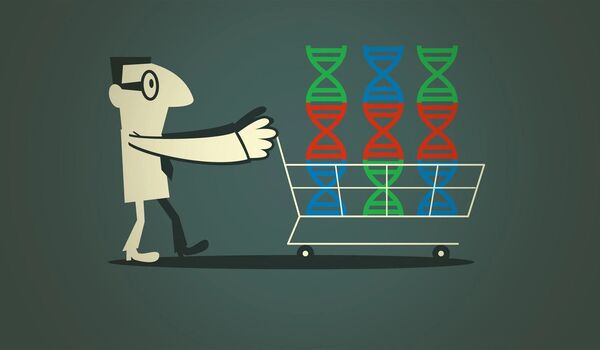

Genetics can influence one’s behavior and health, from risk-taking ability and length of time in school to the likelihood of acquiring Alzheimer’s disease or breast cancer. Although our fate is undoubtedly not inscribed in our genes, firms may find genetic data useful for risk assessment and financial gains, according to a viewpoint published in The American Journal of Human Genetics. The researchers emphasize the importance of legislative safeguards in addressing ethical and policy issues around genetic data collection.

By simply spitting into a tube, at-home DNA testing have given millions of people information about their family history and health risk. Genetic risk screening of embryos at in vitro fertilization facilities is now possible. These tests rely on polygenic scores, which are a tally of variants in human genes that influence a specific attribute. However, while these ratings are effective at predicting features in large groups, they are quite weak at the individual level.

“And for that reason, people have said, ‘we don’t need to worry about companies wanting to use this information at the individual level because it’s not very informative,'” says economist and co-corresponding author Nicholas Papageorge of Johns Hopkins University. “Well, that’s not exactly true. Firms operate under a lot of uncertainty and any little bit of information that they have about you is worthwhile.”

I don’t think people realize that when they give up their genetic information today, they’re not giving it up just for today; they’re giving it up forever. When there’s new science, they know a little bit more about you.

Nicholas Papageorge

Using an economic model, the researchers discovered that corporations may be prepared to pay for a consumer’s polygenic score even if it is only slightly effective as a predictor, because the information can increase profits and is relatively inexpensive. For example, knowing a person’s polygenic score, such as the likelihood of cognitive decline or dangerous behaviors, allows an insurance company to personalize its products to individuals, refuse insurance, or boost premiums.

“And it might be counterintuitive, but there might be welfare-enhancing uses of such data,” adds Michelle Meyer, co-corresponding author, legal scholar, and bioethicist at Geisinger College of Health Sciences.

For example, financial service companies may develop products that reduce financial decision-making burdens or offer error monitoring services for people at high polygenic risk of Alzheimer’s. “But I do think it’s fair to say the burden is on the firm to explicate and help develop appropriate guardrails to prevent nefarious uses.”

The researchers suggest that present laws and procedures are insufficient to address the ethical, privacy, and legal concerns associated with the prospective business use of polygenic scores. While the US Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act forbids discrimination in health care and employment based on genetic information, there are certain exceptions. The act solely applies to health insurance and excludes long-term, disability, life, and other insurances. It also does not apply to organizations with fewer than 15 employees, which account for 85% of US businesses.

“This is a wake-up call to people and to those who are in a position to act,” Meyer says. “We need to put things in place now – or yesterday.”

“I don’t think people realize that when they give up their genetic information today, they’re not giving it up just for today; they’re giving it up forever,” says Papageorge. “When there’s new science, they know a little bit more about you.”