The plumes of smoke crawling upward from Western wildfires have gotten taller in recent years, with more smoke and aerosols lofted up where they can spread farther and impact air quality over a larger area. Climate change is most likely to blame, with decreased precipitation and increased aridity in the Western United States intensifying wildfire activity.

“If these trends continue,” says Kai Wilmot, a postdoctoral researcher in the Department of Atmospheric Sciences at the University of Utah, “it would imply that increased Western U.S. wildfire activity will likely correspond to increasingly frequent degradation of air quality at local to continental scales.”

The study was published in Scientific Reports and was funded by the University of Utah’s iNterdisciplinary EXchange for Utah Science, or NEXUS.

Smoke height

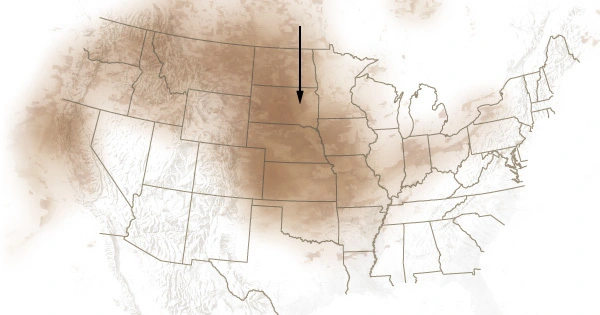

Wilmot and U colleagues Derek Mallia, Gannet Haller, and John Lin modeled plume activity for approximately 4.6 million smoke plumes in the Western United States and Canada between 2003 and 2020 to assess trends in plume height. The researchers looked for trends in the maximum smoke plume height measured during August and September in each region in each year by dividing the plume data according to EPA ecoregions (areas where ecosystems are similar, such as the Great Basin, Colorado Plateau, and Wasatch and Uinta Mountains in Utah).

If these trends continue, it would imply that increased Western U.S. wildfire activity will likely correspond to increasingly frequent degradation of air quality at local to continental scales.

Kai Wilmot

The team discovered that the maximum plume height increased by 750 feet (230 meters) per year in the Sierra Nevada ecoregion of California. Maximum plume heights increased by an average of 320 feet (100 meters) per year in four regions.

Why? Wilmot says that plume heights are a complex interaction between atmospheric conditions, fire size, and the heat released by the fire.

“Given climate-driven trends towards increasing atmospheric aridity, declining snowpack, hotter temperatures, etc., we’re seeing larger and more intense wildfires throughout the Western U.S.,” he says. “And so this is giving us larger burn areas and more intense fires.”

The researchers also employed a smoke plume simulation model to estimate the mass of the plumes and approximate the trends in the amount of aerosols being thrown into the atmosphere by wildfires, which is also increasing.

The smoke simulation model also predicted the formation of pyrocumulonimbus clouds, a phenomenon in which smoke plumes begin to form thunderstorms with their own weather systems. Six ecoregions experienced their first known pyrocumulonimbus clouds between 2017 and 2020, indicating an increase in pyrocumulonimbus activity on the Colorado Plateau.

Taller plumes carry more smoke to higher elevations, where it can spread further, according to John Lin, an atmospheric sciences professor.

“When smoke is lifted to higher altitudes, it has the potential to travel longer distances, degrading air quality across a larger region,” he says. “As a result, wildfire smoke can progress from a more localized issue to a regional or even continental issue.”

Are the trends accelerating?

In recent years, some of the most severe fire seasons have occurred. Does this imply that the rate of the worsening fire trend is quickening? Wilmot believes it is too early to tell. Additional years of data will be required to determine whether anything significant has changed.

“Many of the most extreme data points fall between 2017 and 2020,” he says, “with some of the 2020 values absolutely towering over the rest of the time series.” “Furthermore, given what we know about the 2021 fire season, analysis of 2021 data appears likely to support this finding.”

In Utah’s Wasatch and Uinta Mountains ecoregion, trends of plume height and aerosol amounts are rising but the trends are not as strong as those in Colorado or California. Smoke from neighboring states, however, often spills into Utah’s mountain basins.

“In terms of plume trends, it does not appear that Utah is the epicenter of this issue,” Wilmot says. “However, given our general downwind position from California, trends in plume top heights and wildfire emissions in California suggest a growing risk to Utah air quality as a result of wildfire activity in the West.”

Wilmot claims that, while people can help by preventing human-caused wildfires, climate change is a much bigger and stronger force driving the West’s trends of less precipitation, higher aridity, and riper fire conditions.

“The reality is that some of these [climate change] impacts are already baked in, even if we cut emissions right now,” Wilmot adds. “It seems like largely we’re along for the ride at the moment.”