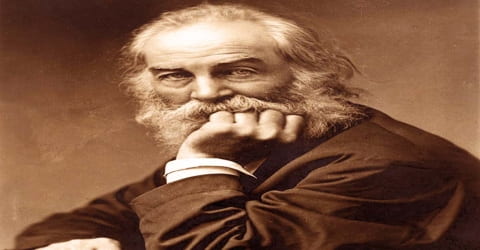

Biography of Walt Whitman

Walt Whitman – American poet, essayist, and journalist.

Name: Walter “Walt” Whitman

Date of Birth: May 31, 1819

Place of Birth: West Hills, New York, U.S.

Date of Death: March 26, 1892 (aged 72)

Place of Death: Camden, New Jersey, U.S.

Father: Walter Whitman

Mother: Louisa Van Velsor

Occupation: Poet, Essayist, Journalist

Early Life

Walt Whitman was an American poet, journalist, and essayist whose verse collection Leaves of Grass, first published in 1855, is a landmark in the history of American literature. He was born on May 31, 1819, in West Hills, New York.

Walt, the second child, attended public school in Brooklyn, began working at the age of 12, and learned the printing trade. He was employed as a printer in Brooklyn and New York City, taught in country schools on Long Island, and became a journalist. At the age of 23 he edited a daily newspaper in New York, and in 1846 he became editor of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, a fairly important newspaper of the time. Discharged from the Eagle early in 1848 because of his support for the antislavery Free Soil faction of the Democratic Party, he went to New Orleans, Louisiana, where he worked for three months on the Crescent before returning to New York via the Mississippi River and the Great Lakes.

A humanist, he was a part of the transition between transcendentalism and realism, incorporating both views in his works. Whitman is among the most influential poets in the American canon, often called the father of free verse. His work was very controversial in its time, particularly his poetry collection Leaves of Grass, which was described as obscene for its overt sexuality.

In 1855 he self-published the collection Leaves of Grass; the book is now a landmark in American literature, though at the time of its publication it was considered highly controversial. Whitman later worked as a volunteer nurse during the Civil War, writing the collection Drum-Taps (1865) in connection to the experiences of war-torn soldiers. Having continued to produce new editions of Leaves of Grass along with original works, Whitman died on March 26, 1892, in Camden, New Jersey.

Childhood, Family and Educational Life

Walt Whitman, in full Walter Whitman, was born May 31, 1819, West Hills, Long Island, New York, U.S. His ancestry was typical of the region: his mother, Louisa Van Velsor, was Dutch, and his father, Walter Whitman, was of English descent. They were farm people with little formal education. The second of nine children, he was immediately nicknamed “Walt” to distinguish him from his father. Walter Whitman, Sr. named three of his seven sons after American leaders: Andrew Jackson, George Washington, and Thomas Jefferson. The oldest was named Jesse and another boy died unnamed at the age of six months. The couple’s sixth son, the youngest, was named Edward.

At age four, Whitman moved with his family from West Hills to Brooklyn, living in a series of homes, in part due to bad investments. Whitman looked back on his childhood as generally restless and unhappy, given his family’s difficult economic status. One happy moment that he later recalled was when he was lifted in the air and kissed on the cheek by the Marquis de Lafayette during a celebration in Brooklyn on July 4, 1825.

Walt attended public school in Brooklyn, began working at the age of 12, and learned the printing trade. Young Whitman took to reading at an early age. By 1830 his formal education was over, and for the next five years, he learned the printing trade. For about five years, beginning in 1836, he taught school on Long Island; during this time he also founded the weekly newspaper Long-Islander.

His father’s increasing dependence on alcohol and conspiracy-driven politics contrasted sharply with his son’s preference for a more optimistic course more in line with his mother’s disposition. “I stand for the sunny point of view,” he’d eventually be quoted as saying.

Personal Life

Whitman was a vocal proponent of temperance and in his youth rarely drank alcohol. He once stated he did not taste “strong liquor” until he was 30 and occasionally argued for prohibition. Later in life, he was more liberal with alcohol, enjoying local wines and champagne.

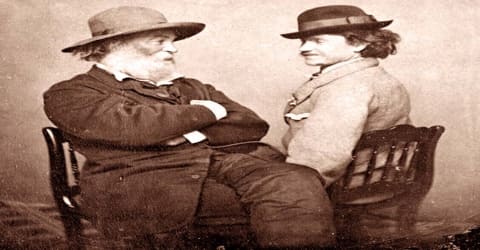

He is usually described as either homosexual or bisexual in his feelings and attractions. Whitman’s sexual orientation is generally assumed on the basis of his poetry, though this assumption has been disputed. Whitman had intense friendships with many men and boys throughout his life. Some biographers have suggested that he may not have actually engaged in sexual relationships with males, while others cite letters, journal entries, and other sources that they claim as proof of the sexual nature of some of his relationships.

(Whitman and Peter Doyle, one of the men with whom Whitman was believed to have had an intimate relationship)

Peter Doyle may be the most likely candidate for the love of Whitman’s life. Doyle was a bus conductor whom Whitman met around 1866, and the two were inseparable for several years. Interviewed in 1895, Doyle said: “We were familiar at once I put my hand on his knee we understood. He did not get out at the end of the trip, in fact, went all the way back with me.” In his notebooks, Whitman disguised Doyle’s initials using the code “16.4” (P.D. being the 16th and 4th letters of the alphabet). Oscar Wilde met Whitman in America in 1882 and told the homosexual-rights activist George Cecil Ives that Whitman’s sexual orientation was beyond question “I have the kiss of Walt Whitman still on my lips.”

There is also some evidence that Whitman may have had sexual relationships with women. He had a romantic friendship with a New York actress, Ellen Grey, in the spring of 1862, but it is not known whether it was also sexual. He still had a photograph of her decades later, when he moved to Camden, and he called her “an old sweetheart of mine”. In a letter, dated August 21, 1890, he claimed, “I have had six children two are dead”. This claim has never been corroborated. Toward the end of his life, he often told stories of previous girlfriends and sweethearts and denied an allegation from the New York Herald that he had “never had a love affair”. As Whitman biographer, Jerome Loving wrote, “the discussion of Whitman’s sexual orientation will probably continue in spite of whatever evidence emerges.”

Career and Works

Whitman had spent a great deal of his 36 years walking and observing in New York City and Long Island. He had visited the theatre frequently and seen many plays of William Shakespeare, and he had developed a strong love of music, especially opera. During these years, he had also read extensively at home and in the New York libraries, and he began experimenting with a new style of poetry. While a schoolteacher, printer, and journalist, he had published sentimental stories and poems in newspapers and popular magazines, but they showed almost no literary promise.

When he was 17, Whitman turned to teaching, working as an educator for five years in various parts of Long Island. Whitman generally loathed the work, especially considering the rough circumstances he was forced to teach under, and by 1841 he again set his sights on journalism. In 1838 he had started a weekly called the Long Islander that quickly folded (though the publication would eventually be reborn) and later returned to New York City, where he worked on fiction and continued his newspaper career. In May 1836, he rejoined his family, now living in Hempstead, Long Island. Whitman taught intermittently at various schools until the spring of 1838, though he was not satisfied as a teacher.

In 1846 he became editor of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, a prominent newspaper, serving in that capacity for almost two years.

After his teaching attempts, Whitman went back to Huntington, New York, to found his own newspaper, the Long-Islander. Whitman served as publisher, editor, pressman, and distributor and even provided home delivery. After ten months, he sold the publication to E. O. Crowell, whose first issue appeared on July 12, 1839. There are no known surviving copies of the Long-Islander published under Whitman. By the summer of 1839, he found a job as a typesetter in Jamaica, Queens with the Long Island Democrat, edited by James J. Brenton. He left shortly thereafter and made another attempt at teaching from the winter of 1840 to the spring of 1841. One story, possibly apocryphal, tells of Whitman’s being chased away from a teaching job in Southold, New York, in 1840. After a local preacher called him a “Sodomite”, Whitman was allegedly tarred and feathered.

During this time, Whitman published a series of ten editorials, called “Sun-Down Papers From the Desk of a Schoolmaster”, in three newspapers between the winter of 1840 and July 1841. In these essays, he adopted a constructed persona, a technique he would employ throughout his career.

Whitman moved to New York City in May, initially working a low-level job at the New World, working under Park Benjamin, Sr. and Rufus Wilmot Griswold. He continued working for short periods of time for various newspapers; in 1842 he was editor of the Aurora and from 1846 to 1848 he was editor of the Brooklyn Eagle.

In 1848 Whitman left New York for New Orleans, where he became editor of the Crescent. It was a relatively short stay for Whitman just three months but it was where he saw for the first time the wickedness of slavery.

Whitman returned to Brooklyn in the autumn of 1848 and started a new “free soil” newspaper called the Brooklyn Freeman, which eventually became a daily despite initial challenges. Over the ensuing years, as the nation’s temperature over the slavery question continued to rise, Whitman’s own anger over the issue elevated as well. He often worried about the impact of slavery on the future of the country and its democracy. It was during this time that he turned to a simple 3.5 by 5.5-inch notebook, writing down his observations and shaping what would eventually be viewed as trailblazing poetic works.

In 1852, he serialized a novel titled Life and Adventures of Jack Engle: An Auto-Biography: A Story of New York at the Present Time in which the Reader Will Find Some Familiar Characters in six installments of New York’s The Sunday Dispatch. In 1858, Whitman published a 47,000 word series called Manly Health and Training under the pen name Mose Velsor. Apparently, he drew the name Velsor from Van Velsor, his mother’s family name. This self-help guide recommends beards, nude sunbathing, comfortable shoes, bathing daily in cold water, eating meat almost exclusively, plenty of fresh air, and getting up early each morning. Present-day writers have called Manly Health and Training “quirky”, “so over the top”, “a pseudoscientific tract”, and “wacky”.

By the spring of 1855, Whitman had enough poems in his new style for a thin volume. Unable to find a publisher, he sold a house and printed the first edition of Leaves of Grass at his own expense. No publisher’s name and no author’s name appeared on the first edition in 1855. But the cover had a portrait of Walt Whitman, “broad-shouldered, rouge-fleshed, Bacchus-browed, bearded like a satyr,” as Bronson Alcott described him in a journal entry in 1856. Though little appreciated upon its appearance, Leaves of Grass was warmly praised by the poet and essayist Ralph Waldo Emerson, who wrote to Whitman on receiving the poems that it was “the most extraordinary piece of wit and wisdom” America had yet contributed.

In a lengthy preface, Whitman announced that his poetry would celebrate the greatness of the new nation – “The Americans of all nations at any time upon the earth have probably the fullest poetical nature. The United States themselves are essentially the greatest poem” and of its peoples – “The largeness of nature or the nation were monstrous without a corresponding largeness and generosity of the spirit of the citizen.” Of the twelve poems (the titles were added later), “Song of Myself,” “The Sleepers,” “There Was a Child Went Forth,” and “I Sing the Body Electric” are the best known today. In these Whitman turned his back on the literary models of the past. He stressed the rhythms of common American speech, delighting in informal and slang expressions.

On July 11, 1855, a few days after Leaves of Grass was published, Whitman’s father died at the age of 65. During the first publications of Leaves of Grass, Whitman had financial difficulties and was forced to work as a journalist again, specifically with Brooklyn’s Daily Times starting in May 1857. As an editor, he oversaw the paper’s contents, contributed book reviews, and wrote editorials. He left the job in 1859, though it is unclear whether he was fired or chose to leave. Whitman, who typically kept detailed notebooks and journals, left very little information about himself in the late 1850s.

For the second edition of Leaves of Grass (1856), Whitman added twenty new poems to his original twelve. With this edition, he began his lifelong practice of adding new poems to Leaves of Grass and revising those previously published in order to bring them into line with his present moods and feelings. Also, over the years he was to drop a number of poems from Leaves.

Among the new poems in the 1856 edition were “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry” (one of Whitman’s masterpieces), “Salut au Monde!,” “A Woman Waits for Me,” and “Spontaneous Me.” Most of the 1855 preface he reworked to form the nationalistic poem “By Blue Ontario’s Shore.” Like the first edition, the second sold poorly.

The third edition of Leaves (1860) was brought out by a Boston publisher, one of the few times in his career that Whitman did not have to publish Leaves of Grass at his own expense. This edition, referred to by Whitman as his “new Bible,” contained the earlier poems plus one hundred forty-six new ones. For the first time Whitman arranged many of the poems in special groupings, a practice he continued in all later editions. The most notable of these “groups” were “Children of Adam,” a gathering of love poems, and “Calamus,” a group of poems celebrating the brotherhood and comradeship of men, or, in Whitman’s phrase, “manly love.”

After the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861, Whitman’s brother was wounded at Fredericksburg, and Whitman went there in 1862, staying some time in the camp, then take a temporary post in the paymaster’s office in Washington. He spent his spare time visiting wounded and dying soldiers in the Washington hospitals, spending his scanty salary on small gifts for Confederate and Union soldiers alike and offering his usual “cheer and magnetism” to try to alleviate some of the mental depression and bodily suffering he saw in the wards.

The Whitman family had a difficult end to 1864. On September 30, 1864, Whitman’s brother George was captured by Confederates in Virginia, and another brother, Andrew Jackson, died of tuberculosis compounded by alcoholism on December 3. That month, Whitman committed his brother Jesse to the Kings County Lunatic Asylum. Whitman’s spirits were raised, however, when he finally got a better-paying government post as a low-grade clerk in the Bureau of Indian Affairs in the Department of the Interior, thanks to his friend William Douglas O’Connor. O’Connor, a poet, daguerreotypist and an editor at The Saturday Evening Post, had written to William Tod Otto, Assistant Secretary of the Interior, on Whitman’s behalf. Whitman began the new appointment on January 24, 1865, with a yearly salary of $1,200. A month later, on February 24, 1865, George was released from capture and granted a furlough because of his poor health. By May 1, Whitman received a promotion to a slightly higher clerkship and published Drum-Taps.

‘Drum-Taps’ represented a more solemn realization of what the Civil War meant for those in the thick of it as seen with poems like “Beat! Beat! Drums!” and “Vigil Strange I Kept on the Field One Night.” A follow up edition, Sequel, was published the same year and featured 18 new poems, including his elegy on President Abraham Lincoln, “When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d.

Following the Civil War and the publication of the fourth edition, Whitman’s poetry became increasingly preoccupied with themes relating to the soul, death, and immortality (living forever). He was entering the final phase of his career. Within the span of some dozen years, the poet of the body had given way to the poet of internationalism (not concentrating on a single country) and the cosmic (relating to the universe). Such poems as “Whispers of Heavenly Death,” “Darest Thou Now O Soul,” “The Last Invocation,” and “A Noiseless Patient Spider,” with their emphasis on the spiritual, paved the way for “Passage to India” (1871), Whitman’s most important (and ambitious) poem of the post–Civil War period.

Whitman was ill in 1872, probably as a result of long-experienced emotional strains; in January 1873 his first stroke left him partly paralyzed. By May he had recovered sufficiently to travel to his brother’s home in Camden, New Jersey, where his mother was dying. Her subsequent death he called “the great cloud” of his life. He thereafter lived with his brother in Camden, and his post in the attorney general’s office was terminated in 1874.

In 1881 Whitman settled on the final arrangement of the poems in Leaves of Grass, and thereafter no revisions were made. All new poems were written after 1881 were added as annexes (additions) to Leaves. The seventh edition was published by James Osgood. The Boston district attorney threatened prosecution against Osgood unless certain poems were removed. When Whitman refused, Osgood dropped publication of the book. However, a Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, publisher reissued the book in 1882.

While in Southern New Jersey, Whitman spent a good portion of his time in the then quite pastoral community of Laurel Springs, between 1876 and 1884, converting one of the Stafford Farm buildings to his summer home. The restored summer home has been preserved as a museum by the local historical society. Part of his Leaves of Grass was written here, and in his Specimen Days, he wrote of the spring, creek, and lake. To him, Laurel Lake was “the prettiest lake in: either America or Europe.”

As the end of 1891 approached, he prepared a final edition of Leaves of Grass, a version that has been nicknamed the “Deathbed Edition.” He wrote, “L. of G. at last complete after 33 y’rs of hackling at it, all times & moods of my life, fair weather & foul, all parts of the land, and peace & war, young & old.” Preparing for death, Whitman commissioned a granite mausoleum shaped like a house for $4,000 and visited it often during construction. In the last week of his life, he was too weak to lift a knife or fork and wrote: “I suffer all the time: I have no relief, no escape: it is monotony—monotony—monotony—in pain.”

Whitman’s greatest theme is a symbolic identification of the regenerative power of nature with the deathless divinity of the soul. His poems are filled with a religious faith in the processes of life, particularly those of fertility, sex, and the “unflagging pregnancy” of nature: sprouting grass, mating birds, phallic vegetation, the maternal ocean, and planets in formation (“the journey-work of stars”). The poetic “I” of Leaves of Grass transcends time and space, binding the past with the present and intuiting the future, illustrating Whitman’s belief that poetry is a form of knowledge, the supreme wisdom of humankind.

Awards and Honor

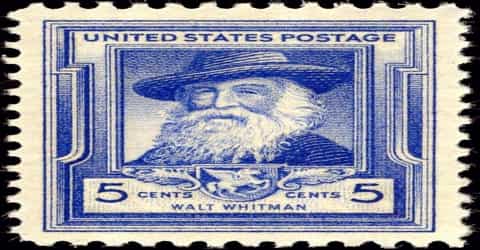

(Whitman was honored on a ‘Famous Americans Series’ Postal issue, in 1940)

The Walt Whitman Bridge, which crosses the Delaware River near his home in Camden, was opened on May 16, 1957. In 1997, the Walt Whitman Community School opened, becoming the first private high school catering to LGBT youth. His other namesakes include Walt Whitman High School (Bethesda, Maryland), Walt Whitman High School (Huntington Station, New York), the Walt Whitman Shops (formerly called “Walt Whitman Mall”) in Huntington Station, Long Island, New York, near his birthplace, and Walt Whitman Road located in Huntington Station and Melville, New York.

Whitman was inducted into the New Jersey Hall of Fame in 2009, and, in 2013, he was inducted into the Legacy Walk, an outdoor public display that celebrates the LGBT history and people.

A statue of Whitman by Jo Davidson is located at the entrance to the Walt Whitman Bridge and another casting resides in the Bear Mountain State Park.

A coed summer camp founded in 1948 in Piermont, New Hampshire is named after Whitman.

Death and Legacy

In his last years, Whitman received the respect due to a great literary figure and personality. He died on March 26, 1892, in Camden, New Jersey. An autopsy revealed his lungs had diminished to one-eighth their normal breathing capacity, a result of bronchial pneumonia, and that an egg-sized abscess on his chest had eroded one of his ribs. The cause of death was officially listed as “pleurisy of the left side, consumption of the right lung, general miliary tuberculosis, and parenchymatous nephritis.”

A public viewing of his body was held at his Camden home; over 1,000 people visited in three hours. Whitman’s oak coffin was barely visible because of all the flowers and wreaths left for him. Four days after his death, he was buried in his tomb at Harleigh Cemetery in Camden. Another public ceremony was held at the cemetery, with friends giving speeches, live music, and refreshments. Whitman’s friend, the orator Robert Ingersoll, delivered the eulogy. Later, the remains of Whitman’s parents and two of his brothers and their families were moved to the mausoleum.

Leaves of Grass has been widely translated, and Whitman’s reputation is now worldwide.

Despite the previous outcry surrounding his work, Whitman is considered one of America’s most groundbreaking poets, having inspired an array of dedicated scholarship and media that continues to grow. Books on the writer include the award-winning Walt Whitman’s America: A Cultural Biography (1995), by David S. Reynolds, and Walt Whitman: The Song of Himself (1999), by Jerome Loving.

Information Source: