A fascinating example of the dramatic changes that cross-cultural interaction can bring about in individual lives is Sake (Sheikh) Dean Mahomed (Bengali: শেখ দীন মোহাম্মদ; شیخ دین محمد), an explorer, writer, Indian traveler, surgeon, and entrepreneur. He was one of the most prominent early non-European Western World immigrants. His name is sometimes pronounced in different ways because of his foreign origin. Before immigrating to Cork in Ireland, he was a soldier for the East India Company, where he published his Travels, the first English book by an Indian. He married and had numerous children with the Irish Protestant gentry. He brought Indian cuisine and shampoo baths to Europe, where therapeutic massage was provided.

(Sake Dean Mahomed)

In May 1759, in the city of Patna, then part of the Bengal Presidency in British India, Sake Deen Mahomed was born into a revered Muslim family that boasted of being related to the Bengal Nawab. In Patna, Dean Mahomed grew up. His father served in the Bengal Army of the East India Company and died in battle when Mahomed was approximately 11 years old. His family had historically been employed by the Muslim rulers of north India, but Muslim power was in decline and the East India Company was in the ascendancy, rapidly expanding its political and economic influence, and offering willing Indians good job prospects in the process. He was taken under the wing of Captain Godfrey Evan Baker, an Anglo-Irish Protestant officer, following his father’s death.

Mahomed worked as a trainee surgeon in the British East India Company’s army, and he also left the army when Captain Baker resigned in 1782, following his adoptive father back to Britain. In eastern Bengal, Baker and Dean Mahomed spent some time traveling (present-day Bangladesh). They visited Dhaka, then a major manufacturing town famous for its Muslin witnessed a spectacular pageant organized annually by the ruling Nawab, and returned to Calcutta by boat through the densely forested Sunderbans, infested with both tigers and robbers.

Mahomed immigrated with the Baker family to Cork, Ireland, in 1784. He studied there at a local school to develop his English language skills, and fell in love with Jane Daly, a “pretty Irish girl of respectable parentage”. The Daly family opposed their relationship because at that time it was illegal for Protestants to marry non-Protestants, so the pair eloped to another city to marry in 1786 and converted Mahomed from Islam to Anglicanism. The couple returned to Cork and Mahomed possibly served as a clerk for the next two decades in the Baker household. He met the Indian traveler Mirza Abu Taleb Khan in 1799, who left an account of the meeting in a travel memoir.

He published “The Travels of Dean Mahomed”, the first book in English by an Indian author, in 1794. Mahomed described his service and adventures in the British army, the towns of India, and his contentious marriage to Jane Daly in the novel. According to leading historians, and as suggested by parish records in London, in 1806, Mahomed married Jane Jeffreys (1780-1850) in Marylebone; the banns were read on 24th August for Jane and “William Mahomet.” He had a daughter by her, Amelia (b. 1808), and is listed in the parish registers as the father, “William Dean Mahomet.” At St Marylebone, Westminster, in London, Amelia was baptized on 11th June 1809. Sake Dean Mahomed had seven children by his legal wife: Rosanna, Henry, Horatio, Frederick, Arthur, and Dean Mahomed (baptized in St. Finbarr’s Roman Catholic Church, Cork, in 1791).

The full title of the book is “The Travels of Dean Mahomet”, A Native of Patna in Bengal, Through Many Parts of India, Though Written by Himself in the Service of The Honorable the East India Company, In a Series of Letters to a Friend. It conforms to a common convention in English writing of the age while using the epistolary style. The Mahomeds moved to London in 1807, where he found employment with the Honorable Basil Cochrane, a Scottish nobleman who made a fortune in India and now opened a vapor bath therapy establishment. Dean Mahomed began working as a medical practitioner in London, although the job was similar to a spa worker than to a doctor. Mahomed served in a steam bath and added the ritual of “chāmpo”, the root of the English term “shampoo”, a Hindi word referring to a head massage with oils.

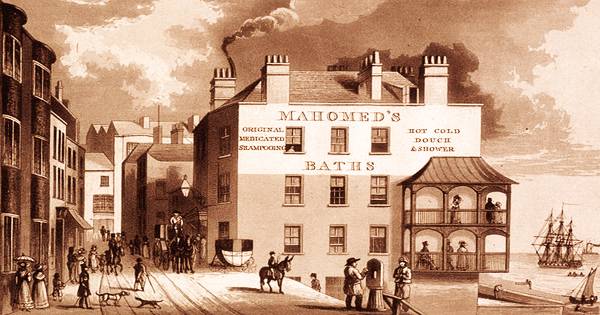

Mahomed was a restaurateur from 1809 to 1812; his ‘Hindustanee Coffee House’ offered Indian cuisine in an Indian atmosphere built with the aid of cane furniture, hookahs, and Oriental paintings in the posh Portman Square. While successful initially, the venture ended in the bankruptcy of Mahomed. In 1814, on the site now occupied by the Queen’s Hotel, Mahomed and his wife moved back to Brighton to open the first commercial “shampooing” vapor masseur bath in England. He described the treatment in a local paper as “The Indian Medicated Vapour Bath (a type of Turkish bath), a cure to many diseases and giving full relief when everything fails; particularly Rheumatic and paralytic, gout, stiff joints, old sprains, lame legs, aches and pains in the joints.” This business was an instant success and became known as “Dr. Brighton” to Dean Mahomed. Hospitals referred him to patients and both King George IV and William IV were named as shampoo surgeons.

Mahomed wrote two books for advertising, in addition to newspaper ads, first ‘Cases Cured by Sake Dean Mahomed, Shampooing Surgeon, And Inventor of the Indian Medicated Vapour And Sea-Water Baths, Written by the Patients Themselves’ (1820), and subsequently three editions of ‘Shampooing’, or, ‘Benefits Resulting from the use of The Indian Medicated Vapour Bath’, As Introduced into this Country by SD Mahomed, in which, before becoming a soldier, he claimed to have qualified and worked as a physician, and added ten years to his age to make the fib plausible.

(Dean Mahomed’s Baths, Brighton, 1826)

In this post, Mahomed talks about the initial opposition to the concept of shampooing among the English he encountered in his new country:

“It is not in the power of any individual to give unqualified satisfaction or to attempt to establish a new opinion without the risk of incurring the ridicule, as well as censure, of some portion of mankind. So it was with me: in the face of indisputable evidence, I had to struggle with doubts and objections raised and circulated against my Bath, which, but for the repeated and numerous cures effected by it, would long since have shared the common fate of most innovations in science.”

As he treated King George IV and King William IV and was given Warrants of Appointment as “Shampoo Surgeon” to their majesties, the height of Mahomed’s career came. Mahomed opened a branch in London sometime in the 1830s, first-run by his son, Deen Junior, and then by another son, Horatio, who also published two advertisement books. On 24th February 1851 (aged 91-92) at 32 Grand Parade, Brighton, Dean Mahomed died. He was buried in a grave in the Church of St Nicholas, Brighton, where his son Frederick was later buried. At a gymnasium he constructed on the town’s Church Lane, Frederick taught fencing, gymnastics, and other sports in Brighton.

(Dean Mahomed was buried at St Nicholas’ Church, Brighton)

His obituaries revealed that his business acumen was lacking. But there is no doubt that his personality was extremely colorful, and he deserves to be remembered for introducing two very different traditions; one is the tradition of Indo-Anglian literature, and the other is that of Indians themselves selling Indian exotica. In the 21st century, many commemorations and tributes to Mahomed’s legacy have taken place. A Green Plaque commemorating the opening of the Hindoostane Coffee House was unveiled on 29th September 2005 by the City of Westminster. The plaque is at 102 George Street, near to the coffee house’s original location at 34 George Street. On January 15, 2019, Sake Dean Mahomed was remembered by Google with a Google Doodle on the main page.

Information Sources: