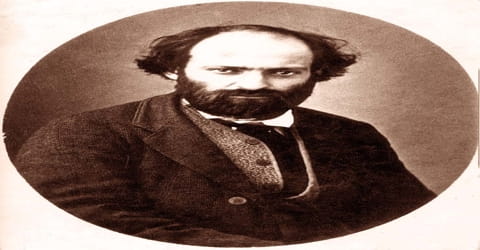

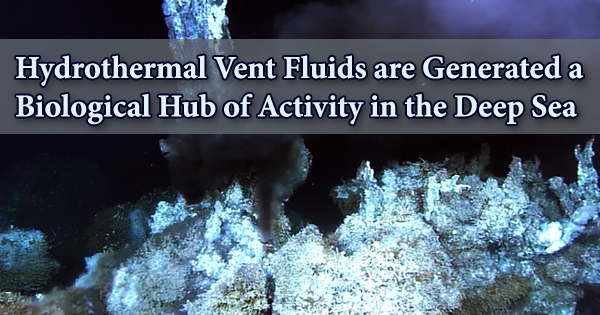

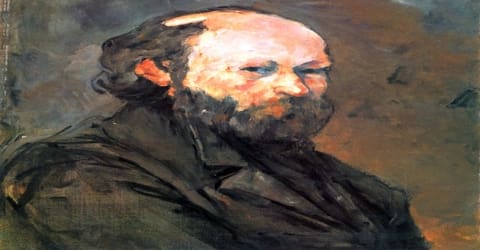

Biography of Paul Cezanne

Paul Cezannet – French artist and Post-Impressionist painter.

Name: Paul Cezanne

Date of Birth: 19 January 1839

Place of Birth: Aix-en-Provence, France

Date of Death: 22 October 1906 (aged 67)

Place of Death: Aix-en-Provence, France

Occupation: Painter

Father: Louis-Auguste Cézanne

Mother: Anne-Elisabeth Honorine Aubert

Spouse/Ex: Marie-Hortense Fiquet (M. 1886)

Early Life

Paul Cézanne, French painter, one of the greatest of the Post-Impressionists, was born on 19 January 1839 in Aix-en-Provence, France. On 22 February, he was baptized in the Église de la Madeleine, with his grandmother and uncle Louis as godparents, and became a devout Catholic later in life. The mastery of design, tone, composition, and color that spans his life’s work is highly characteristic and now recognizable around the world. Both Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso were greatly influenced by Cézanne.

Cézanne studied art in Paris but was not very comfortable with the city and thus, preferred to work from his hometown, Aix, and shuttled to Paris from time to time. This disquiet in his life is visible in the rough style of his early works. During his time in Paris, he worked alongside contemporaries such as Edouard Manet, Claude Monet, and Camille Pissarro. With constant feedback and mentoring of Camille Pissarro, he moved from dour tones and heavy emotions to brighter hues and lesser aggressive themes, such as pastoral or rural scenes and landscapes. Pissarro and he worked ‘en plein air’ depicting the southern French countryside like no other artists before them. The reverence and joy with which he painted his greatest inspiration nature is reflected in all his works. Much of modern art, especially ‘cubism’, owes a lot to the artist and his aesthetics.

His works and ideas were influential in the aesthetic development of many 20th-century artists and art movements, especially Cubism. Cézanne’s art, misunderstood and discredited by the public during most of his life, grew out of Impressionism and eventually challenged all the conventional values of painting in the 19th century because of his insistence on personal expression and on the integrity of the painting itself, regardless of subject matter.

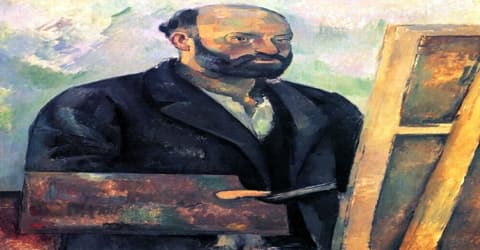

Cézanne’s brushwork and use of color is held in high esteem by modern artists, and his influence can be seen in every cubist work of art, even today. His paintings are put on display at the Louvre and the Metropolitan Museum and the Museum of Modern Art. Scroll further to learn more about this personality.

He is said to have formed the bridge between late 19th-century Impressionism and the early 20th century’s new line of artistic enquiry, Cubism. Both Matisse and Picasso are said to have remarked that Cézanne “is the father of us all.”

Childhood, Family and Educational Life

Famed painter Paul Cézanne was born in Aix-en-Provence, France, on January 19, 1839, to Louis-Auguste and Anne Elisabeth Honorine Aubert. His father was a native of Saint-Zacharie (Var), was the co-founder of a banking firm (Banque Cézanne et Cabassol) that prospered throughout the artist’s life, affording him financial security that was unavailable to most of his contemporaries and eventually resulting in a large inheritance. His mother was “vivacious and romantic, but quick to take offence”. It was from her that Cézanne got his conception and vision of life. He also had two younger sisters, Marie and Rose, with whom he went to a primary school every day.

Cézanne attended primary school along with his younger sisters, Marie and Rose, and then went on to study at Saint Joseph School, in Aix. He enrolled to College Bourbon (currently College Mignet) in 1852, where he formed an inseparable kinship with Emile Zola and Baptistin Baille.

This friendship was important for both men: with the youthful spirit, they dreamed of successful careers in the Paris art world, Cézanne as a painter and Zola as a writer. Consequently, Cézanne began to study painting and drawing at the École des Beaux-Arts (School of Design) in Aix in 1856. His father was against the pursuit of an artistic career, and in 1858 he persuaded Cézanne to enter law school at the University of Aix. Although Cézanne continued his law studies for several years, at the same time he was enrolled in the École des Beaux-Arts in Aix, where he remained until 1861.

In 1861, Cézanne finally convinced his father to allow him to go to Paris, where he planned to join Zola and enroll at the Académie des Beaux-Arts (now the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris). His application to the academy was rejected, however, so he began his artistic studies at the Académie Suisse instead. Though Cézanne had gained inspiration from visits to the Louvre particularly from studying Diego Velázquez and Caravaggio he found himself crippled by self-doubt after five months in Paris. Returning to Aix, he entered his father’s banking house but continued to study at the School of Design.

Personal Life

In 1886 Cézanne married Marie-Hortense Fiquet, a model with whom he had been living for seventeen years. Also, his father died that same year. Probably the most significant event of this year, however, was the publication of the novel L’Oeuvre by Cézanne’s friend Zola. The hero of the story is a painter (generally acknowledged to be a composite of Cézanne and Manet) who is presented as an artistic failure. Cézanne took this presentation as a critical denunciation of his own career, which hurt him deeply, and he never spoke to Zola again. In January 1872 Marie-Hortense gave birth to a son.

By 1888 the family was in the former manor, Jas de Bouffan, a substantial house and grounds with outbuildings, which afforded a new-found comfort. This house, with much-reduced grounds, is now owned by the city and is open to the public on a restricted basis.

Career and Works

The early 1860s was a period of great vitality for Parisian literary and artistic activity. The conflict had reached its height between the Realist painters, led by Gustave Courbet, and the official Académie des Beaux-Arts, which rejected from its annual exhibition and thus from public acceptance all paintings, not in the academic Neoclassical or Romantic styles. Cézanne’s paintings from the 1860s are odd and bear little resemblance to the artist’s mature and more important style. The subject matter is dark and depressing and includes fantasies, dreams, religious images, and a general theme concerned with death.

He was an established artist by the mid-1860s and most of his paintings used baleful, heavy tones and were characterized by morbid themes. Around this time, by Napoleon III’s decree, the works of young Impressionists painters were showcased at the ‘Salon des Refuses’ instead of the usual, ‘Academie des Beaux-Arts’.

Cézanne was interested in the simplification of naturally occurring forms to their geometric essentials: he wanted to “treat nature by the cylinder, the sphere, the cone” (a tree trunk may be conceived of as a cylinder, an apple or orange a sphere, for example). Additionally, Cézanne’s desire to capture the truth of perception led him to explore binocular vision graphically, rendering slightly different, yet simultaneous visual perceptions of the same phenomena to provide the viewer with an aesthetic experience of depth different from those of earlier ideals of perspective, in particular, single-point perspective. His interest in new ways of modelling space and volume derived from the stereoscopy obsession of his era and from reading Hippolyte Taine’s Berkelean theory of spatial perception. Cézanne’s innovations have prompted critics to suggest such varied explanations as sick retinas, pure vision, and the influence of the steam railway.

Paul Cézanne’s paintings from the 1860s are peculiar, bearing little overt resemblance to the artist’s mature and more important style. The subject matter is brooding and melancholy and includes fantasies, dreams, religious images and a general preoccupation with the macabre. His technique in these early paintings is similarly romantic, often impassioned. For his “Man in a Blue Cap” (also called “Uncle Dominique,” 1865-1866), he applied pigments with a palette knife, creating a surface everywhere dense with impasto. The same qualities characterize Cézanne’s unique “Washing of a Corpse” (1867-1869), which seems to both portray events in a morgue and be a pieta – a representation of the biblical Virgin Mary.

(The Black Marble Clock 1869–1871)

A fascinating aspect of Cézanne’s style in the 1860s is its sense of energy. Each piece seems the work of an artist who could be either madman or genius. That Cézanne would evolve into the latter, however, can in no way be known from these earlier examples. Although Cézanne received encouragement from Pissarro and other artists during the 1860s and enjoyed the occasional critical backing of his friend Zola, his pictures were consistently rejected by the annual salons (art exhibitions in France) and earned him harsh criticism.

Most of Cezanne’s early works were inspired by the Impressionist works of these dejected artists, but his strained personal ties with them led to his usage of murky tones in his work. From 1861 to 1870, Cezanne painted a series of paintings with a palette knife and called these works ‘une couillarde’. His later paintings and sketches from the period between 1867 and 1869 were based on suggestive and intense themes, including ‘Women Dressing’, ‘The Rape’ and ‘The Murder’. When the Franco-Prussian War commenced, Cezanne and his mistress settled in Marseilles, France, where he began painting landscapes.

In July 1870, with the outbreak of the Franco-German War, Cézanne left Paris for Provence, partly to avoid being drafted. He took with him Marie-Hortense Fiquet, a young woman who had become his mistress the previous year and whom he married in 1886. The Cézannes settled at Estaque, a small village on the coast of southern France, not far from Marseille. There he began to paint landscapes, exploring ways to depict nature faithfully and at the same time to express the feelings it inspired in him. He began to approach his subjects the way his Impressionist friends did; in two landscapes from this time, Snow at Estaque (1870–71) and The Wine Market (1872), the composition is that of his early style, but already more disciplined and more attentive to the atmospheric, rather than dramatic, quality of light.

In 1872 Cézanne moved to Pontoise, France, where he spent two years working very closely with Pissarro. During this period Cézanne became convinced that one must paint directly from nature. The result was that romantic and religious subjects began to disappear from his canvases. In addition, the dark range of his palette (range of colors) began to give way to fresher, more vibrant colors. Cézanne, as a direct result of his stay in Pontoise, decided to participate in the first exhibition of the Société Anonyme des Artistes Peintres, Sculpteurs et Graveurs in 1874. Radical artists who had been constantly rejected by the official salons organized this historic exhibition. It inspired the term “impressionism,” a revolutionary art form where the “impression” of a scene or object is generated and light is simulated by primary colors.

A direct result of his stay in Pontoise, Cézanne decided to participate in the first exhibition of the “Société Anonyme des artistes, peintres, sculptures, graveurs, etc.” in 1874. This historic exhibition, which was organized by radical artists who’d been persistently rejected by the official Salons, inspired the term “Impressionism” originally a derogatory expression coined by a newspaper critic marking the start of the now-iconic 19th-century artistic movement. The exhibit would be the first of eight similar shows between 1874 and 1886. After 1874, however, Cézanne exhibited in only one other Impressionist show the third, held in 1877 to which he submitted 16 paintings.

(Jas de Bouffan, 1876)

After 1877 Cézanne gradually withdrew from the impressionists and worked in increasing isolation at his home in southern France. This withdrawal was linked with two factors. First, the more personal direction his work began to take, a direction not taken by the other impressionists. Second, the disappointing responses that his art continued to generate among the public at large. In fact, Cézanne did not show his art publicly for almost twenty years after the third impressionist show.

In March 1878, Cézanne’s father found out about Hortense and threatened to cut Cézanne off financially, but, in September, he relented and decided to give him 400 francs for his family. Cézanne continued to migrate between the Paris region and Provence until Louis-Auguste had a studio built for him at his home, Bastide du Jas de Bouffan, in the early 1880s. This was on the upper floor, and an enlarged window was provided, allowing in the northern light but interrupting the line of the eaves. This feature remains today. Cézanne stabilized his residence in L’Estaque. He painted with Renoir there in 1882 and visited Renoir and Monet in 1883.

Cézanne’s paintings from the 1870s are a testament to the influence that the Impressionist movement had on the artist. In “House of the Hanged Man” (1873-1874) and “Portrait of Victor Choque” (1875-1877), he painted directly from the subject and employed short, loaded brushstrokes characteristic of the Impressionist style as well as the works of Monet, Renoir, and Pissarro. But unlike the way the movement’s originators interpreted the Impressionist style, Cézanne’s Impressionism never took on a delicate aesthetic or sensuous feel; his Impressionism has been deemeed strained and discomforting as if he were fiercely trying to coalesce color, brushstroke, surface, and volume into a more tautly unified entity.

In the early 1880s, the Cézanne family stabilized their residence in Provence where they remained, except for brief sojourns abroad, from then on. The move reflects new independence from the Paris-centered impressionists and a marked preference for the south, Cézanne’s native soil. Hortense’s brother had a house within view of Montagne Sainte-Victoire at Estaque. A run of paintings of this mountain from 1880 to 1883 and others of Gardanne from 1885 to 1888 are sometimes known as “the Constructive Period”.

After his father’s death in 1886, Cézanne became financially independent. He had married Marie-Hortense six months earlier, and, after a year in Paris in 1888, Marie-Hortense and their son moved there permanently. Cézanne himself then settled in Aix except for a few visits to the capital, to Fontainebleau, to Jura in Switzerland, and to the home of Monet in Giverny, where he met the sculptor Auguste Rodin. In 1895 the art dealer Ambroise Vollard set up the first one-man exhibition of Cézanne’s work (more than 100 canvases), but, although young artists and some art lovers were beginning to show enthusiasm for his painting, the public remained unreceptive.

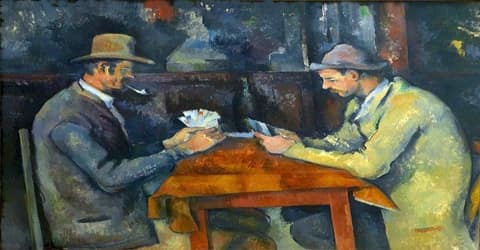

“Les joueurs de cartes” (The Card Players), 1892–95, oil on canvas

Cézanne’s paintings were not well received among the petty bourgeoisie of Aix. In 1903 Henri Rochefort visited the auction of paintings that had been in Zola’s possession and published on 9 March 1903 in L’Intransigeant a highly critical article entitled “Love for the Ugly”. Rochefort describes how spectators had supposedly experienced laughing fits when seeing the paintings of “an ultra-impressionist named Cézanne”. The public in Aix was outraged, and for many days, copies of L’Intransigeant appeared on Cézanne’s door-mat with messages asking him to leave the town “he was dishonoring”.

Cézanne’s paintings from the last three decades of his life established new paradigms for the development of modern art. Working slowly and patiently, the painter transformed the restless power of his earlier years into the structuring of a pictorial language that would go on to impact nearly every radical phase of 20th-century art.

This new language is apparent in many of Cézanne’s works, including “Bay of Marseilles from L’Estaque” (1883-1885); “Mont Sainte-Victoire” (1885-1887); “The Cardplayers” (1890-1892); “Sugar Bowl, Pears and Blue Cup” (1866); and “The Large Bathers” (1895-1905). Each of these works seems to confront the viewer with its identity as a work of art; landscapes, still lifes and portraits seem to spread out in all directions across the surface of the canvas, demanding the viewer’s full attention.

Cézanne’s isolation in Aix began to lessen during the 1890s. In 1895, owing largely to the urging of Pissarro, Monet, and Renoir, the dealer Ambroise Vollard (1865–1939) showed a large number of Cézanne’s paintings, and public interest in his work slowly began to develop. In 1899, 1901, and 1902 Cézanne sent pictures to the annual Salon des Indépendants in Paris. By 1904, a whole studio was allotted to him to keep his works. The studio still exists and is known as the ‘Atelier Paul Cezanne’.

Awards and Honor

At the Salon d’Automne of 1907 Cézanne’s achievement was honored with a large retrospective exhibition (an exhibit that shows an artist’s life work).

To honor his memory, a Cezanne Medal, is granted by the city of Aix en Provence for special achievement in the field of art.

Death and Legacy

In 1904 Cézanne was given an entire room at the Salon d’Automne. While painting outdoors in the fall of 1906 Cézanne was overtaken by a storm and became ill. He died a few days later, on 22 October 1906 of pneumonia and was buried at the Saint-Pierre Cemetery in his hometown of Aix-en-Provence.

‘Compotier, Pitcher, and Fruit’, painted between 1892 and 1894, is considered one of his famous paintings, for its texture and shadows. The painting depicts everyday objects yet expresses complex emotions through the use of harmonious colors. This technique and depth is said to have revolutionized art during the 20th century. ‘Les grandes baigneuses’, which he worked on from 1898 to 1905, is considered one of his masterpieces and is often studied for the varying levels of detail and symmetrical dimensions and the positions of the nudes in the painting.

Cézanne used short, hatched brushstrokes to help ensure surface unity in his work as well as to model individual masses and spaces as if they themselves were carved out of paint. These brushstrokes have been credited with employing 20th century Cubism’s analysis of form. Furthermore, Cézanne simultaneously achieved flatness and spatiality through his use of color, as color, while unifying and establishing surface, also tends to affect interpretations of space and volume; by calling primary attention to a painting’s flatness, the artist was able to abstract space and volume which are subject to their medium (the material used to create the work) for the viewer. This characteristic of Cézanne’s work is viewed as a pivotal step leading up to the abstract art of the 20th century.

Cézanne’s paintings from the last twenty-five years of his life led to the development of modern art. Working slowly and patiently, he developed a style that has affected almost every radical phase of twentieth-century art. This new form is apparent in many works, including the Bay of Marseilles from L’Estaque (1883–1885), Mont Sainte-Victoire (1885–1887), the Cardplayers (1890–1892), the White Sugar Bowl (1890–1894), and the Great Bathers (1895–1905).

Over the years the public has also embraced his work, although, as his first biographer, Julius Meier-Graef, observed in 1904, “Except for Van Gogh, no one in modern art has made stronger demands on aesthetic receptivity than Cézanne.” Cézanne is now recognized as the most significant precursor of 20th-century formal abstraction in painting, as he developed a purely pictorial language that balanced analysis with emotion and structure with lyricism. Picasso offered the most succinct assessment of Cézanne’s role for subsequent generations of artists, declaring that he was “the father of us all.”

Information Source: