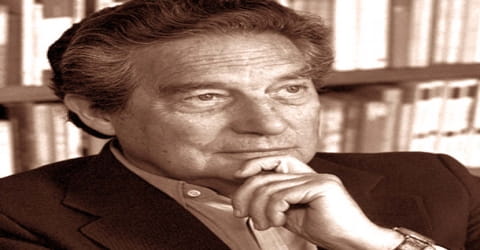

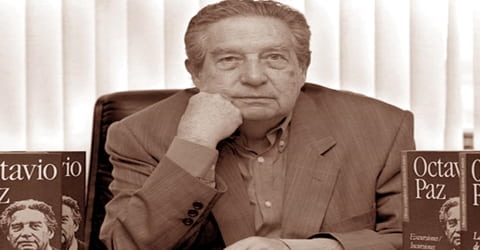

Biography of Octavio Paz

Octavio Paz – Mexican poet and diplomat.

Name: Octavio Paz Lozano

Date of Birth: March 31, 1914

Place of Birth: Mexico City, Mexico

Date of Death: April 19, 1998 (aged 84)

Place of Death: Mexico City, Mexico

Father: Octavio Paz Solórzano

Mother: Josefina Lozano

Occupation: Writer, Poet, Diplomat

Spouse: Marie-José Tramini (m. 1965–1998), Elena Garro (m. 1937–1959)

Children: Helena

Early Life

Octavio Paz was born into a family of writers on March 31, 1914, in Mexico City. He was a Mexican poet and diplomat. As his father was a member of a revolutionary group, young Octavio spent his early childhood under the care of his grandfather, also a noted writer. The elder Paz kept an extensive library and Octavio was introduced to both Mexican and European literature through these books while he was still a child. He began writing at the age of eight and had his first book of poems published at nineteen. Later he joined Mexican diplomatic service and it was during his stint as Ambassador to India that he had the opportunity to study Hindu and Buddhist philosophies which influenced his later writings.

Although known as a leftist writer, Paz did not support Cuban leader Fidel Castro or the Sandinista guerrilla movement of Nicaragua. He later said, “Revolution begins as a promise, is squandered in violent agitation, and freezes into bloody dictatorships that are the negation of the fiery impulse that brought it into being.”

In 1933, he published his first collection of poems, Luna Silvestre. Several years later, he founded and edited a literary magazine called Taller. Over his lifetime, he produced more than 20 books and poetry collections and received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1990.

Childhood, Family and Educational Life

Octavio Paz, in full Octavio Paz Lozano, was born on March 31, 1914, in Mexico City into a distinguished family of Spanish and Indian descent. His father, Octavio Paz Solórzano, was a prominent lawyer and journalist. He served as a counsel for Mexican revolutionary Emiliano Zapata and took a decisive part in his 1911 agrarian uprising.

With his son away, it fell upon Octavio’s grandfather, Ireneo Paz, also a political activist and writer, to look after the family. In 1915, he took the mother and child to his house in Mixcoac; a pre-Hispanic town, located just outside the Mexican City, but now a part of it. There, young Octavio was brought up by his mother, Josefina Lozano, aunt, Amalia Paz, and grandfather. Their big magnificent house, the surrounding garden as well as the cobbled streets of the town left an everlasting impression on his mind and were later reflected in many of his works.

Octavio attended a Roman Catholic school as a child and later studied at the University of Mexico, where he received English public style education. He turned to writing as an escape from the financial strains his family suffered due to the Mexican Civil War, and at age 19 published his first book of poetry, Luna silvestre.

Personal Life

In 1937, Octavio Paz married Elena Garro, also a Mexican writer of great repute. The couple had a daughter named Helena Laura Paz Garro. Their marriage broke up in 1959. However, Elena always claimed that they were not officially divorced and if any such paper existed, it was fraudulent.

In 1965, he married Marie-José Tramini, a French lady, with whom he lived until his death.

Career and Works

As a teenager in 1931, Paz published his first poems, including “Cabellera”. Two years later, at the age of 19, he published Luna Silvestre (“Wild Moon”), a collection of poems. In 1932, with some friends, he founded his first literary review, Barandal. In 1937 at the age of 23, Paz abandoned his law studies and left Mexico City for Yucatán to work at a school in Mérida, set up for the sons of peasants and workers. There, he began working on the first of his long, ambitious poems, “Entre la piedra y la flor” (“Between the Stone and the Flower”) (1941, revised in 1976). Influenced by the work of T. S. Eliot, it explores the situation of the Mexican peasant under the domineering landlords of the day.

Paz was also a skilled editor and helped found a literary magazine called Taller in 1938. He entered the diplomatic service in 1945 and was later appointed the Mexican ambassador to India, a position he held from 1962 to 1968. Paz resigned in protest over the Mexican government’s handling of student demonstrations during the Olympic Games.

In 1932, Octavio Paz Lozano entered National Autonomous University of Mexico. Here he was drawn to the leftist movement. Along with his studies and political activism, he also concentrated on writing, publishing a number of poems in the same year. One of the more well-known poems published around that time was ‘Cabellera.’ His first article, ‘Etica del artista’ (Ethics of the Artist), was also published in the same period.

However, his most noteworthy achievement of this period was the founding of an avant-garde literary magazine titled, ‘Barandal’ (handrail) with three friends, Rafael López Malo, Salvador Toscano, and Arnulfo Martínez Lavalle.

In 1937, Paz was invited to the Second International Writers Congress in Defense of Culture in Spain during the country’s civil war; he showed his solidarity with the Republican side and against fascism. Upon his return to Mexico, Paz co-founded a literary journal, Taller (“Workshop”) in 1938, and wrote for the magazine until 1941.

In 1938, on his return to Mexico, Octavio Paz co-founded two literary journals, ‘Taller’ meaning workshop and ‘El Hijo Pródigo’, meaning the child prodigy. Concurrently, he resumed his work on ‘Entre la piedra y la flor’, the long poem he had started at Mérida and had it published in 1941.

In 1943, Paz won a two-year Guggenheim fellowship and used it to study Anglo American Modernist poetry at the University of California. During this period, he also traveled all over the United States of America.

In 1945, he was sent to Paris, where he wrote El Laberinto de la Soledad (“The Labyrinth of Solitude”). The New York Times later described it as “an analysis of modern Mexico and the Mexican personality in which he described his fellow countrymen as instinctive nihilists who hide behind masks of solitude and ceremoniousness.” In 1952, he traveled to India for the first time. That same year, he went to Tokyo, as chargé d’affaires. He next was assigned to Geneva, Switzerland. He returned to Mexico City in 1954, where he wrote his great poem “Piedra de sol” (“Sunstone”) in 1957, and published Libertad bajo palabra (Liberty under Oath), a compilation of his poetry up to that time. He was sent again to Paris in 1959. In 1962, he was named Mexico’s ambassador to India.

As a product of many “isms,” including Marxism, Surrealism, existentialism, Buddhism, and Hinduism, Paz’s extremely complex and diverse work incorporates a multitude of themes. His essays are personal accounts rather than historical analyses, and his true talent lies in his ability to connect his own beliefs with all of these different schools of thought in his work.

His service as a Mexican diplomat took him to France where he wrote renowned essay, El laberinto de la soledad, analyzing the Mexican people by means of their culture and history. He also served as Mexican ambassador to India from 1962-1968, where he wrote The Grammarian Monkey and East Slope, two pivotal works in his career. He resigned from Mexico’s diplomacy in 1968 because he opposed the government brutally suppressing a student demonstration at the Olympic Gamed in Tlateloco. After the 1968 tragedy, Paz changed his views about Mexico and added the Posdata to El laberinto de la soledad.

He now took the opportunity to study Hindu and Buddhist philosophies. However, his interest was more intellectual than religious. During this period, he also came in close contact with the members of ‘Hungry Generation’, a group of avant-garde poets based in Kolkata and exerted considerable influence on them.

On October 2, 1968, back in Mexico, an estimated 300 students and civilians were killed by Mexican military and police in the Plaza de las Tres Culturas in the Tlatelolco section of Mexico City. Hearing this, Paz resigned from his post in protest. He founded his magazine Plural (1970–1976) with a group of liberal Mexican and Latin American writers.

From 1969 to 1970 he was Simón Bolívar Professor at Cambridge University. He was also a visiting lecturer during the late 1960s and the A. D. White Professor-at-Large from 1972 to 1974 at Cornell University. In 1974 he lectured at Harvard University as Charles Eliot Norton Lecturer. His book Los hijos del limo (“Children of the Mire”) was the result of those lectures. After the Mexican government closed Plural in 1975, Paz founded Vuelta, another cultural magazine. He was editor of that until his death in 1998 when the magazine closed.

Paz is recognized throughout Latin America and the world for his literary work in cultural studies, which is perhaps the most repeated theme of his work. It is difficult to place his essays into a certain field of study; his thoughts and views reflect sociology, anthropology, and philosophy simultaneously. For example, the theme of El laberinto de la soledad is the identification of the Mexican people derived from both Mexican history and the comparison of Mexico with its neighbors, especially the United States. This theme has foundations in sociology, such as the way present-day Mexico is a product of its past, but also in philosophy, in the existential sense that the Mexicans are searching for who they are and feel inferior to the United States.

Once good friends with novelist Carlos Fuentes, Paz became estranged from him in the 1980s in a disagreement over the Sandinistas, whom Paz opposed and Fuentes supported. In 1988, Paz’s magazine Vuelta published criticism of Fuentes by Enrique Krauze, resulting in estrangement between Paz and Fuentes, who had long been friends.

A collection of Paz’s poems (written between 1957 and 1987) was published in 1990.

Adept at both poetry and prose, Paz moved back and forth between the two genres throughout his career. Poetry, such as Piedra de sol (1957), and critical and analytical works, such as El Laberinto de la soledad (1950) cemented his reputation as a master of language and a keen intellect. He produced more than 30 books and poetry collections in his lifetime.

“The poetry of Octavio Paz”, wrote the critic Ramón Xirau, “does not hesitate between language and silence; it leads into the realm of silence where true language lives.”

Also in 1970, he co-founded ‘Plural’, a literary magazine, with a group of liberal Mexican and Latin American writers. When in 1975, the Mexican government banned ‘Plural’, he founded another cultural magazine called ‘Vuelta’, remaining its editor till his death.

Paz’s other works translated into English include several volumes of essays, some of the more prominent of which are Alternating Current (tr. 1973), Configurations (tr. 1971), in the UNESCO Collection of Representative Works, The Labyrinth of Solitude (tr. 1963), The Other Mexico (tr. 1972); and El Arco y la Lira (1956; tr. The Bow and the Lyre, 1973). In the United States, Helen Lane’s translation of Alternating Current won a National Book Award. Along with these are volumes of critical studies and biographies, including of Claude Lévi-Strauss and Marcel Duchamp (both, tr. 1970), and The Traps of Faith, an analytical biography of Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, the Mexican 17th-century nun, feminist poet, mathematician, and thinker.

His works include the poetry collections ¿Águila o sol? (1951), La Estación Violenta, (1956), Piedra de Sol (1957), and in English translation, the most prominent include two volumes that include most of Paz in English: Early Poems: 1935–1955 (tr. 1974), and Collected Poems, 1957–1987 (1987). Many of these volumes have been edited and translated by Eliot Weinberger, who is Paz’s principal translator into American English.

Awards and Honor

In 1990, Octavio Paz Lozano received the Nobel Prize in Literature “for impassioned writing with wide horizons, characterized by sensuous intelligence and humanistic integrity.”

Inducted Member of Colegio Nacional, Mexican highly selective academy of arts and sciences 1967

He won the 1977 Jerusalem Prize for literature on the theme of individual freedom.

In 1980, he was awarded an honorary doctorate from Harvard, and in 1982, he won the Neustadt Prize.

Death and Legacy

Towards the end of his life, he was inflicted with cancer and died from it on April 19, 1998, in Mexico City. The body of work he left behind continues to keep his legacy alive.

Guillermo Sheridan, who was named by Paz as director of the Octavio Paz Foundation in 1998, published a book, Poeta con paisaje (2004) with several biographical essays about the poet’s life up to 1998 when he died.

Among his essays, he is best remembered for ‘El laberinto de la soledad’ (The Labyrinth of Solitude). The work, divided into nine parts, deals primarily with Mexican identity. It also demonstrates how at the end of a labyrinth, there exists an intense feeling of solitude.

A prolific author and poet, Paz published scores of works during his lifetime, many of which have been translated into other languages. His poetry has been translated into English by Samuel Beckett, Charles Tomlinson, Elizabeth Bishop, Muriel Rukeyser, and Mark Strand. His early poetry was influenced by Marxism, surrealism, and existentialism, as well as religions such as Buddhism and Hinduism. His poem, “Piedra de sol” (“Sunstone”), written in 1957, was praised as a “magnificent” example of surrealist poetry in the presentation speech of his Nobel Prize.

Information Source: