Biography of Lillian Wald

Lillian Wald – American nurse.

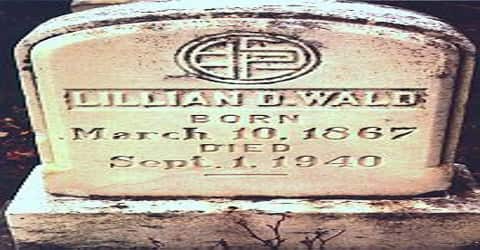

Name: Lillian D. Wald

Date of Birth: March 10, 1867

Place of Birth: Cincinnati, Ohio

Date of Death: September 1, 1940 (aged 73)

Place of Death: Westport, Connecticut

Occupation: Nurse, Humanitarian, Activist

Early Life

American nurse and social worker, Lillian Wald was born on March 10, 1867, into a life of privilege as the daughter of Jewish professionals living in Cincinnati, Ohio. She was known for contributions to human rights and was the founder of American community nursing. She founded the Henry Street Settlement in New York City and was an early advocate to have nurses in public schools.

Lillian was the force behind the formation of Visiting Nurse Service and the Henry Street Settlement (New York). Being an advocate of justice and equality she served people from all sections of the society irrespective of their race and class, thereby promoting health and sanitary awareness amongst them. Her consideration for children and women was commendable wherein she worked on reforms pertaining to child labor and women sufferings. Lillian also worked towards promoting world peace through her pacifism and participation in politics during World War I. She tirelessly worked for suffrage and supported racial integration. She played an important role in the foundation of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

Lillian became an influential leader in the city, state, and national politics. Her efforts to link the health of children with the health of nations made her a model for others to follow. Wald’s achievements, caring, and integrity helped her to gain international recognition. She had an unshakable belief that the world was just an expanded culturally diverse neighborhood. She spent many years at the helm of the Henry Street Settlement. Ill health finally forced her retirement to Westport, Connecticut, where in 1940 she died of a cerebral hemorrhage at the age of 73, has changed the world in countless ways.

Childhood, Family and Educational Life

Lillian D. Wald was born March 10, 1867, Cincinnati, Ohio, U.S. as the third child to Max D. and Minnie Schwartz Wald. Her father who worked as an optical dealer came from a middle-class German-Jewish family of scholars and merchants while her mother had Jewish Polish and Jewish German ancestry. Lillian was deeply influenced by her grandfather, Gutman Schwartz with whom she spent a major part of her childhood.

Coming from an economically sound background, Lillian was enrolled for expensive private schooling at Miss Cruttenden’s English-French Boarding and Day School for Young Ladies where she was trained in French and German. In 1883, at the young age of sixteen, Lillian tried for Vassar College but was not selected due to age issues. Following this, she spent the next few years traveling and serving as a newspaper correspondent.

In 1889, Lillian attended New York Hospital’s School of Nursing. She graduated from the New York Hospital Training School for Nurses in 1891, and then took courses at the Woman’s Medical College. After graduation, Wald worked in the New York Juvenile Asylum and then taught classes in home nursing for poor, immigrant families on New York’s Lower East Side.

Personal Life

Lillian Wald was so devoted to her Henry Street Settlement that she remained unmarried for her entire life. She maintained her closest relationships and attachments with women. Correspondence reveals that Wald felt intimate affection for at least two of her companions, homemaking author Mabel Hyde Kittredge and lawyer and theater manager Helen Arthur. Ultimately, however, Wald was more engaged in her work with Henry Street than in an intimate relationship.

In regard to Wald’s relationships, author Clare Coss writes that Wald “remained in the end forever elusive. She preferred personal independence, which allowed her to move quickly, travel freely and act boldly.” Wald’s personal life and focus on independence were clear in her devotion to the Settlement and improving public health.

Career and Works

In 1889 Lillian broke completely with that life and entered the New York Hospital Training School for Nurses, from which she graduated in 1891. She completed her graduation in March 1891 under the mentorship of Irene H. Sutliffe, the program’s director of nursing, following which she served at the juvenile asylum for a year and eventually resumed studies at the Woman’s Medical College for her M.D. degree.

During her education at the medical college, she also taught home nursing to people in the eastern region of New York. She realized the sad state of the immigrants in this area when a little girl asked for help for her ill mother. She came eye to eye with the reality of the poor and sick and called the experience as ‘baptism by fire’.

For a year she worked as a nurse in the New York Juvenile Asylum. She supplemented her training in 1892–93 with courses at the Woman’s Medical College. She was asked to organize a class in home nursing for the poor immigrant families of New York’s Lower East Side, and in the course of that work, she observed firsthand the wretched conditions within the tenement districts.

Lillian advocated for nursing in public schools. Her ideas led the New York Board of Health to organize the first public nursing system in the world. She was the first president of the National Organization for Public Health Nursing. Wald established a nursing insurance partnership with Metropolitan Life Insurance Company that became a model for many other corporate projects. She suggested a national health insurance plan and helped to found the Columbia University School of Nursing. Wald authored two books relating to her community health work, The House on Henry Street (1911) and Windows on Henry Street (1934).

In the autumn of 1893, with Mary M. Brewster, Wald left medical school, moved to the neighborhood, and offered her services as a visiting nurse. Two years later, with aid from banker-philanthropist Jacob H. Schiff and others, she took larger accommodations and opened the Nurse’s Settlement. As the number of nurses attached to the settlement grew, services were expanded to include nurses’ training, educational programs for the community, and youth clubs. Within a few years, the Henry Street establishment had become a neighborhood center, the Henry Street Settlement.

They together set up the ‘Visiting Nurse Service’ in 1893 and later shifted base to Henry Street in 1895. Gradually, the team grew from 9 trained nurses in 1893 to 15 in 1900 and 27 in 1927.

She founded the Henry Street Settlement. The organization attracted the attention of prominent Jewish philanthropist Jacob Schiff, who secretly provided Wald with money to more effectively help the “poor Russian Jews” whose care she provided. By 1906 Wald had 27 nurses on staff, and she succeeded in attracting broader financial support from such gentiles as Elizabeth Milbank Anderson. By 1913 the staff had grown to 92 people. The Henry Street Settlement eventually developed as the Visiting Nurse Service of New York.

’The Henry settlement’ continued to grow steadily and in 1913 it had nine houses, seven vacation houses, three stock rooms, clinics and a club membership of approximately 3000 people. In 1914, a total of 100 nurses rendered services through the Nurses’ Settlement. Apart from health aid, the Henry Street Settlement offered various other services such as housing, basic education, language, and music lessons, also rendering employment in the process.

Lillian suggested a national health insurance plan and helped found the Columbia University School of Nursing. She pressured the New York City Board of Education to extend educational opportunities to children with physical and learning disabilities, to hire school nurses, and to create school lunch programs.

Over the years the settlement was a powerful source of innovation in the social settlement movement and in the broader field of social work generally. The Neighborhood Playhouse was opened in connection with the settlement in 1915 through the benefaction of Irene Lewisohn. Residents at Henry Street included at various times social reformer Florence Kelley, economist Adolf A. Berle, Jr., labor leader Sidney Hillman, and Henry Morgenthau, Jr., U.S. Secretary of the Treasury under President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Wald exerted considerable influence beyond Henry Street as well.

Her vision for Henry Street was one, unlike any others at the time. Wald believed that every New York City resident was entitled to equal and fair health care regardless of their social status, socio-economic status, race, gender, or age. She argued that everyone should have access to at-home-care. A strong advocate for adequate bed-side manner, Wald believed that regardless of if a person could afford at-home-care, they deserved to be treated with the same level of respect that some who could afford it would be.

Lillian was a major force in the campaigns for social reform and public health, and she was an international crusader for human rights. She worked to abolish child labor and helped establish the Federal Children’s Bureau. She advocated for civil rights, women’s suffrage, and for peace.

In 1902, at her initiative, nursing service was experimentally extended to a local public school, and soon the municipal board of health instituted a citywide public school nursing program, the first such program in the world. The organization of nursing programs by insurance companies for their industrial policyholders (pioneered by the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company in 1909) and of the district nursing service of the Red Cross (begun in 1912 and later called Town and Country Nursing Service) was both at her suggestion.

She worked to create a more just society so that women, children, the poor, immigrants, and people of all ethnic and religious groups would be able to realize the American promise of ‘life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.’

Lillian Wald provided a unique opportunity for women and employment through the Settlement. In her letters, she speaks with donors about the employment opportunities that are provided to women through the Settlement and the many benefits they offer. One of the most notable benefits was the opportunity for women to have a career and to build their own wealth independent of husbands or families. Employment also provided women with the opportunity to gain independence from their husbands and work outside of the home.

In 1910, Lillian Wald and several colleagues went on a six-month tour of Hawaii, Japan, China, and Russia, a trip that increased her involvement in worldwide humanitarian issues

In 1912 Wald’s role as founder of an entirely new profession was formally acknowledged when she helped found and became the first president of the National Organization for Public Health Nursing. She also worked to establish educational, recreational, and social programs in underprivileged neighborhoods. In 1912 Congress established the U.S. Children’s Bureau (headed by Julia Lathrop), also in no small part owing to Wald’s suggestion, and in that year she was awarded the gold medal of the National Institute of Social Sciences.

In 1915, Wald founded the Henry Street Neighborhood Playhouse. She was an early leader of the Child Labor Committee, which became the National Child Labor Committee (NCLC). The group lobbied for federal child labor laws and promoted childhood education. In the 1920s, the organization proposed an amendment to the U.S. Constitution that would have banned child labor.

Lillian Wald’s work in the field of world peace was also commendable. Being a pacifist and the chairman of the American Union Against Militarism (AUAM), she directed her efforts in developing friendly relations with Mexico instead of warfare. She also worked for world peace by protesting United State’s involvement in the World War I through ‘Women’s Peace Party’ and ‘Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom’.

In 1909, she became a founding member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). The organization’s first major public conference opened at the Henry Street Settlement. Lillian organized New York City campaigns for suffrage, marched to protest the entry of the United States into World War I, joined the Woman’s Peace Party and helped to establish the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. In 1915 she was elected president of the newly formed American Union Against Militarism (AUAM). She remained involved with the AUAM’s daughter organizations, the Foreign Policy Organization, and the American Civil Liberties Union after the United States joined the war.

During World War I, Lillian headed the committee on home nursing of the Council of National Defense. She led the Nurses’ Emergency Council in the influenza epidemic of 1918–19. Later she founded the League of Free Nations, a forerunner of the Foreign Policy Association. She wrote two autobiographical books, The House on Henry Street (1915) and Windows on Henry Street (1934). In 1933 ill health forced her to resign as a head worker of Henry Street, and she settled in Westport, Connecticut.

Awards and Honor

(Bust of Lillian Wald at the Hall of Fame for Great Americans)

Lillian was honored by the Gold Medal of the National Institute of Social Sciences (1912), the Rotary Club Medal, and the Better Times Medal.

Lillian Wald was considered as one of the 12 greatest living American women by the New York Times in 1922.

Lillian Wald was elected to the Hall of Fame for Great Americans in 1970. In 1993, Wald was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame. The Lillian Wald Houses on Avenue D in Manhattan was named for her.

Death and Legacy

Lillian D. Wald died of a cerebral hemorrhage on September 1, 1940. She was cremated at a family plot in Rochester, New York. A rabbi conducted a memorial service at Henry Street’s Neighborhood Playhouse. A private service was also held at Wald’s home. A few months later at Carnegie Hall, over 2,000 people gathered at a tribute to Wald that included messages delivered by the president, governor, and mayor.

The New York Times named Wald as one of the 12 greatest living American women in 1922 and she later received the Lincoln Medallion for her work as an “Outstanding Citizen of New York.” In 1937 a radio broadcast celebrated Wald’s 70th birthday, Sara Delano Roosevelt read a letter from her son, President Franklin Roosevelt, in which he praised Wald for her “unselfish labor to promote the happiness and well being of others.”

The Columbia University School of Nursing and the Federal Children’s Bureau were founded by Lillian Wald in 1912. Following which the Town and Country Nursing Service of the American Red Cross were also established by her. Lillian was a civil right activist as well and worked for the equality of different races. She founded the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP)

As a present on her 70th birthday, a letter from President Franklin Roosevelt was officially read on the radio to appreciate Lillian for her selfless and humanitarian efforts for social well-being.

Wald coined the term ‘public health nurse’, to describe the new form of nursing that she developed to assist the poor. Her ideas led the New York Board of Health to develop the first public nursing system in the world. She was the one to introduce the national health insurance plan.

Information Source: