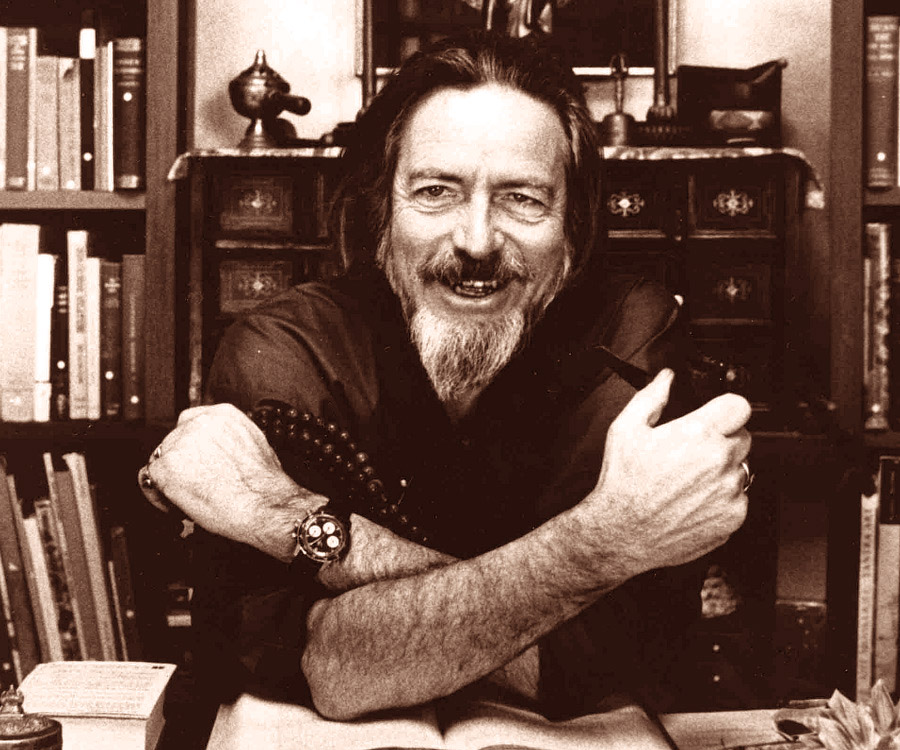

Alan Watts – Philosopher, Writer, and Speaker (1915-1973)

Full name: Alan Wilson Watts

Date of birth: 6 January 1915

Place of birth: Chislehurst, Kent, England

Date of death: 16 November 1973 (aged 58)

Place of death: Mt. Tamalpais, California, United States

Nationality: British and American

Era: Contemporary philosophy

Region: Eastern Philosophy

Main interests: Personal identity, Higher consciousness, Aesthetics, Cultural criticism, Public ethics

Early Life

Alan Wilson Watts was born on 6 January 1915, in Chislehurst, Kent, England. He was a well-known British philosopher, writer and speaker, best known for his interpretation of Eastern philosophy for Western audiences. Born to Christian parents in England, he developed interest in Buddhism while he was still a student at King’s School, Canterbury.

(Birth Place of Alan Watts)

(Birth Place of Alan Watts)

Subsequently, he became a member of Buddhist Lodge, where he met many scholars and spiritual masters, who helped him to shape his ideas. He was a prolific writer and began writing at the age of fourteen. Many of his early works were published in the journal of the Lodge.

He moved to the United States in 1938 and began Zen training in New York. Pursuing a career, he attended Seabury-Western Theological Seminary, where he received a master’s degree in theology. Watts became an Episcopal priest in 1945, then left the ministry in 1950 and moved to California, where he joined the faculty of the American Academy of Asian Studies.

Watts gained a large following in the San Francisco Bay Area while working as a volunteer programmer at KPFA, a Pacifica Radio station in Berkeley. Watts wrote more than 25 books and articles on subjects important to Eastern and Western religion, introducing the then-burgeoning youth culture to The Way of Zen (1957), one of the first bestselling books on Buddhism. In Psychotherapy East and West (1961), Watts proposed that Buddhism could be thought of as a form of psychotherapy and not a religion. He considered Nature, Man and Woman (1958) to be, “from a literary point of view — the best book I have ever written.” He also explored human consciousness, in the essay “The New Alchemy” (1958), and in the book The Joyous Cosmology (1962).

Towards the end of his life, he divided his time between a houseboat in Sausalito and a cabin on Mount Tamalpais. Many of his books are now available in digital format and many of his recorded talks and lectures are available on the Internet. According to the critic Erik Davis, his “writings and recorded talks still shimmer with a profound and galvanizing lucidity.”

Alan Watts was profoundly influenced by the East Indian philosophies of Vedanta and Buddhism, and by Taoist thought, which is reflected in Zen poetry and the arts of China and Japan. After leaving the Church, he never became a member of another organized religion, and although he wrote and spoke extensively about Zen Buddhism, he was criticized by American Buddhist practicioners for not sitting regularly in zazen. Alan Watts responded simply by saying, “A cat sits until it is done sitting, and then gets up, stretches, and walks away.”

Educational Career

Alan Watts attended The King’s School, Canterbury next door to Canterbury Cathedral. Though he was frequently at the top of his classes scholastically and was given responsibilities at school, he botched an opportunity for a scholarship to Oxford by styling a crucial examination essay in a way that was read as presumptuous and capricious.

(Kings School)

(Kings School)

When he left secondary school, Watts worked in a printing house and later a bank. He spent his spare time involved with the Buddhist Lodge and also under the tutelage of a “rascal guru” named Dimitrije Mitrinović. (Mitrinović was himself influenced by Peter Demianovich Ouspensky, G. I. Gurdjieff, and the varied psychoanalytical schools of Freud, Jung and Adler.) Watts also read widely in philosophy, history, psychology, psychiatry and Eastern wisdom. By his own reckoning, and also by that of his biographer Monica Furlong, Watts was primarily an autodidact. His involvement with the Buddhist Lodge in London afforded Watts a considerable number of opportunities for personal growth. Through Humphreys, he contacted eminent spiritual authors (e.g. the artist, scholar, and mystic Nicholas Roerich, Sarvapalli Radhakrishnan, and prominent theosophists like Alice Bailey).

In 1936, aged 21, he attended the World Congress of Faiths at the University of London, heard D. T. Suzuki read a paper, and afterwards was able to meet this esteemed scholar of Zen Buddhism. Beyond these discussions and personal encounters, Watts absorbed, by studying the available scholarly literature, the fundamental concepts and terminology of the main philosophies of India and East Asia.

(University of London)

Buddhism

By his own assessment, Watts was imaginative, headstrong, and talkative. He was sent to boarding schools (which included both academic and religious training of the Muscular Christianity sort) from early years. Of this religious training, he remarked “Throughout my schooling my religious indoctrination was grim and maudlin…”

Watts spent several holidays in France in his teen years, accompanied by Francis Croshaw, a wealthy Epicurean with strong interests in both Buddhism and exotic little-known aspects of European culture. It was not long afterward that Watts felt forced to decide between the Anglican Christianity he had been exposed to and the Buddhism he had read about in various libraries, including Croshaw’s. He chose Buddhism, and sought membership in the London Buddhist Lodge, which had been established by Theosophists, and was now run by the barrister Christmas Humphreys. Watts became the organization’s secretary at 16 (1931). The young Watts explored several styles of meditation during these years.

Seated Great Buddha (Daibutsu), Kamakura, Japan

Career

In 1931, at the age of sixteen, Watts was made the Secretary of the Buddhist Lodge. Sometime during this period, he also came in contact with spiritual authors like, Dr. Sarvapalli Radhakrishnan, Nicholas Roerich and Alice Bailey and imbibed a lot from them.

Watts’s fascination with the Zen (or Ch’an) tradition—beginning during the 1930s—developed because that tradition embodied the spiritual, interwoven with the practical, as exemplified in the subtitle of his Spirit of Zen: A Way of Life, Work, and Art in the Far East. “Work”, “life”, and “art” were not demoted due to a spiritual focus. In his writing, he referred to it as “the great Ch’an (or Zen) synthesis of Taoism, Confucianism and Buddhism after 700 CE in China.” Watts published his first book, The Spirit of Zen, in 1936. Two decades later, in The Way of Zen he disparaged The Spirit of Zen as a “popularisation of Suzuki’s earlier works, and besides being very unscholarly it is in many respects out of date and misleading.”

Watts left formal Zen training in New York because the method of the teacher did not suit him. He was not ordained as a Zen monk, but he felt a need to find a vocational outlet for his philosophical inclinations. He entered Seabury-Western Theological Seminary, an Episcopal (Anglican) school in Evanston, Illinois, where he studied Christian scriptures, theology, and church history. He attempted to work out a blend of contemporary Christian worship, mystical Christianity, and Asian philosophy. Watts was awarded a master’s degree in theology in response to his thesis, which he published as a popular edition under the title Behold the Spirit: A Study in the Necessity of Mystical Religion. He later published Myth & Ritual in Christianity (1953), an eisegesis of traditional Roman Catholic doctrine and ritual in Buddhist terms. However, the pattern was set, in that Watts did not hide his dislike for religious outlooks that he decided were dour, guilt-ridden, or militantly proselytizing—no matter if they were found within Judaism, Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, or Buddhism.

In 1936, he attended the World Congress of Faiths at the University of London, where he met Daisetsu Teitaro Suzuki, esteemed scholar of Zen Buddhism. He had already read his works; the meeting fascinated him to a great extent.

Also in 1936, he published his second book; ‘The Spirit of Zen: A Way of Life, Work and Art in the Far East’. It was followed by ‘The Legacy of Asia and Western Man’ (1937).

In 1938, he left England for the United States of America with his family. Initially they settled in New York, where he began his formal training in Zen Buddhism. Unfortunately, he could not adapt to his teacher’s method and so he left without being ordained as a Zen monk.

Looking for a vocational outlet for his spiritual inclinations, he joined Seabury-Western Theological Seminary, an Episcopal (Anglican) school in Evanston, Illinois. Here he studied Christian scriptures, theology, and church history.

In 1945, on receiving his master’s degree from the seminary, he became an Episcopal priest and joined the Northwestern University at Chicago as its chaplain. He was very popular among the students, who joined him in a spirited discussion on Christian as well as Eastern philosophy.

During his stay at Chicago, Watts wrote three books on Christian mysticism. However, he found it very hard to reconcile his Buddhist beliefs with Christian doctrines. Moreover, he got entangled in an extramarital relationship. So he left Chicago and in early 1951, shifted to San Francisco.

In early 1951, Watts moved to California, where he joined the faculty of the American Academy of Asian Studies in San Francisco. Here he taught from 1951 to 1957 alongside Saburō Hasegawa (1906-1957), Frederic Spiegelberg, Haridas Chaudhuri, lama Tada Tōkan (1890-1967), and various visiting experts and professors. Hasegawa, in particular, served as a teacher to Watts in the areas of Japanese customs, arts, primitivism, and perceptions of nature. It was during this time he met the poet, Jean Burden whom he called an “important influence.” Alan placed a “cryptograph” crediting her in his book “Nature, Man and Woman” to which he alludes in his autobiography. Besides teaching, Watts served for several years as the Academy’s administrator. One notable student of his was Eugene Rose, who later went on to become a noted Orthodox Christian hieromonk and controversial theologian within the Orthodox Church in America under the jurisdiction of ROCOR. Rose’s own disciple, a fellow monastic priest published under the name Hieromonk Damascene, produced a book entitled Christ the Eternal Tao, in which the author draws parallels between the concept of the Tao in Chinese philosophy and the concept of the Logos in classical Greek philosophy and Eastern Christian theology.

He also seized the opportunity to learn Chinese language as well as Chinese brush calligraphy. Apart from that, he studied many other subjects ranging from Vedanta to quantum mechanics and cybernetics.

Sometime now, he also started experimenting with psychedelic drugs and its effect on mystical insight. He began by taking mescaline. Next in 1958, he worked with several other researchers on LSD, taking the drugs several times. Later he worked with marijuana and wrote about their effects in his forthcoming books.

In 1953, he began what became a long-running weekly radio program at Pacifica Radio station KPFA in Berkeley. Like other volunteer programmers at the listener-sponsored station, Watts was not paid for his broadcasts. These weekly broadcasts continued until 1962, by which time he had attracted a “legion of regular listeners”. Watts continued to give numerous talks and seminars, recordings of which were broadcast on KPFA and other radio stations during his life.

In 1957 Watts, then 42, published one of his best known books, The Way of Zen, which focused on philosophical explication and history. Besides drawing on the lifestyle and philosophical background of Zen, in India and China, Watts introduced ideas drawn from general semantics (directly from the writings of Alfred Korzybski) and also from Norbert Wiener’s early work on cybernetics, which had recently been published. Watts offered analogies from cybernetic principles possibly applicable to the Zen life. The book sold well, eventually becoming a modern classic, and helped widen his lecture circuit.

Watts’s explorations and teaching brought him into contact with many noted intellectuals, artists, and American teachers in the human potential movement. His friendship with poet Gary Snyder nurtured his sympathies with the budding environmental movement, to which Watts gave philosophical support. He also encountered Robert Anton Wilson, who credited Watts with being one of his “Lights along the Way” in the opening appreciation of Cosmic Trigger. Werner Erhard attended workshops given by Alan Watts and said of him, “He pointed me toward what I now call the distinction between Self and Mind. After my encounter with Alan, the context in which I was working shifted.”

Watts has been criticized by Buddhists such as Philip Kapleau and D. T. Suzuki for allegedly misinterpreting several key Zen Buddhist concepts. In particular, he drew criticism from those who believe that zazen must entail a strict and specific means of sitting, as opposed to a cultivated state of mind available at any moment in any situation. Typical of these is Kapleau’s claim that Watts dismissed zazen on the basis of only half a koan. In regard to the aforementioned koan, Robert Baker Aitken reports that Suzuki told him, “I regret to say that Mr. Watts did not understand that story.” In his talks, Watts addressed the issue of defining zazen practice by saying, “A cat sits until it is tired of sitting, then gets up, stretches, and walks away.”

In his writings of the 1950s, he conveyed his admiration for the practicality in the historical achievements of Chán (Zen) in the Far East, for it had fostered farmers, architects, builders, folk physicians, artists, and administrators among the monks who had lived in the monasteries of its lineages. In his mature work, he presents himself as “Zennist” in spirit as he wrote in his last book, Tao: The Watercourse Way. Child rearing, the arts, cuisine, education, law and freedom, architecture, sexuality, and the uses and abuses of technology were all of great interest to him. Though known for his Zen teachings, he was also influenced by ancient Hindu scriptures, especially Vedanta, and spoke extensively about the nature of the divine reality which Man misses: how the contradiction of opposites is the method of life and the means of cosmic and human evolution; how our fundamental Ignorance is rooted in the exclusive nature of mind and ego; how to come in touch with the Field of Consciousness and Light, and other cosmic principles. These are discussed in great detail in dozens of hours of audio that are in part captured in the ‘Out of Your Mind’ series.

From early 1960s, he went to Japan several times. Also from 1962 to 1964, he had a fellowship at Harvard University and in 1968, became a scholar at San Jose State University. In fact, by the late 1960s, he had become a counterculture celebrity with many followers as well as critics.

Soon he began travelling widely to speak at universities and growth centers across the US and Europe and by early 1970s, he became the most important interpreter of Eastern thoughts in the Western world.

In regards to his ethical outlook, Watts felt that absolute morality had nothing to do with the fundamental realization of one’s deep spiritual identity. He advocated social rather than personal ethics. In his writings, Watts was increasingly concerned with ethics applied to relations between humanity and the natural environment and between governments and citizens. He wrote out of an appreciation of a racially and culturally diverse social landscape.

Watts led some tours for Westerners to the Buddhist temples of Japan. He also studied some movements from the traditional Chinese martial art taijiquan, with an Asian colleague, Al Chung-liang Huang.

Watts’ books frequently include discussions reflecting his keen interest in patterns that occur in nature and which are repeated in various ways and at a wide range of scales – including the patterns to be discerned in the history of civilizations.

Personal Information

Alan Wilson Watts was born on 6 January 1915 in Chislehurst village in Kent, now south-east London. His father, Laurence Wilson Watts, was an employee of Michelin Tyre Company while his mother, Emily Mary Watts (née Buchan), was a homemaker.

(Alan Watts, age seven)

As the only child of his parents, Alan grew up playing alone by the brook, learning to identify wildflowers and butterflies. Another factor that had an immense influence on his upbringing was his mother’s family, which was religiously inclined.

Watts also later wrote of a mystical dream he experienced while ill with a fever as a child. During this time he was influenced by Far Eastern landscape paintings and embroideries that had been given to his mother by missionaries returning from China. The few Chinese paintings Watts was able to see in England riveted him, and he wrote “I was aesthetically fascinated with a certain clarity, transparency, and spaciousness in Chinese and Japanese art. It seemed to float…”. These works of art emphasized the participatory relationship of man in nature, a theme that stood fast throughout his life, and one that he often writes about.

Alan Watts married three times and had seven children (five daughters and two sons).

In 1936, he met Eleanor Everett at the Buddhist Lodge and got married in April 1938. Their eldest daughter Joan was born in November 1938 and the younger daughter Anne in 1942.

Towards the end of 1940s, Watts became entangled with an extramarital affair with Jean Burden; as a result Eleanor had their marriage annulled. Although he never married Jean, she remained in his thought till the end. He also kept in touch with his mother-in-law Ruth Fuller Everett.

In 1950, Watts married Dorothy DeWitt. They had five children; Tia, Mark, Richard, Lila, and Diane. The marriage ended when in early 1960s Watts met Mary Jane Yates King while on a lecture tour to New York. The divorce was granted in 1964 and Watts and King got married in the same year.

Watts’ eldest daughters, Joan Watts and Anne Watts, own and manage most of the copyrights to his books. His son, Mark Watts, serves as curator of his father’s audio, video and film and has published content of some of his spoken lectures in print format.

Death

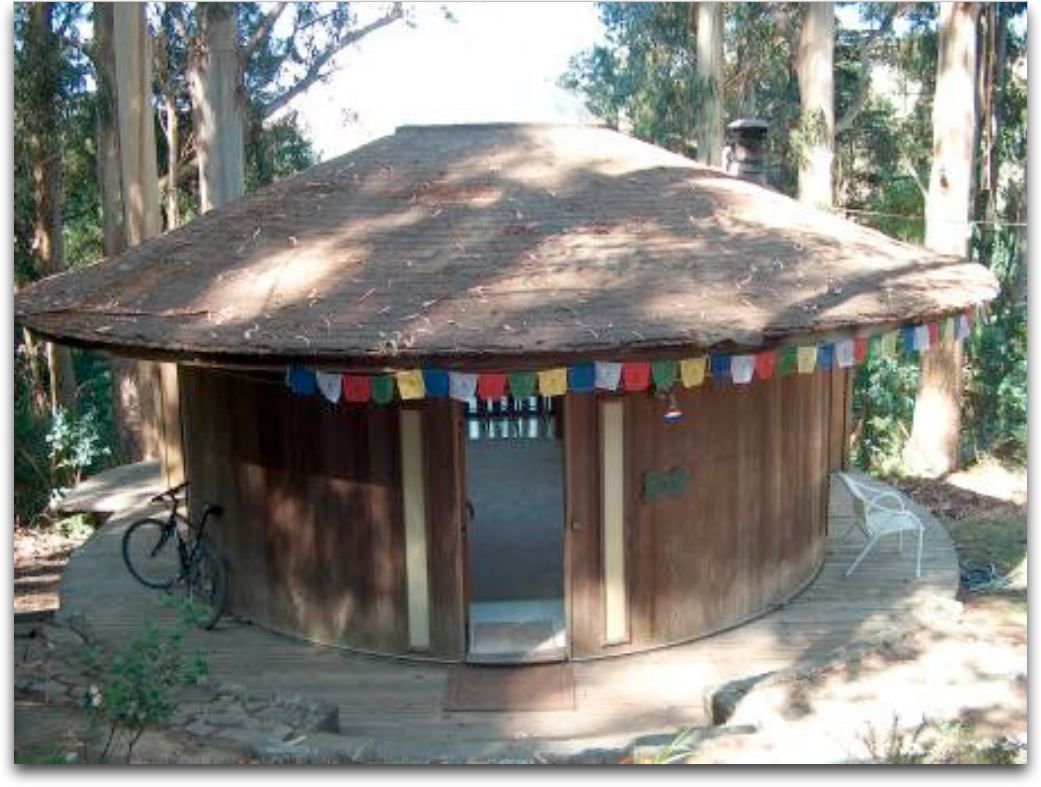

Until the middle of 1960s Watts lived with King in Sausalito, California. Subsequently, he began to divide his time between Sausalito and Druid Heights, located on the southwest flank of Mount Tamalpais. Here he lived in a secluded cabin. At the same time, he continued with his lecture trips.

In October 1973, he returned from one such trip to Europe and put up at his cabin in Druid Heights. There he died in sleep on 16 November 1973. His body was cremated and half of the ashes were buried near his library at Druid Heights while the other half at the Green Gulch Monastery.

(Alan Watts Library)

(Alan Watts Library)

(Green Gulch Monastery)

(Green Gulch Monastery)

Watts has left around 25 books as well as an audio library of nearly 400 talks, which carry his legacy to this day. To cater to their ever-increasing demand, his books are not only being republished now, copies of his audio lectures are also being published in written format.

Saybrook University in the USA offers a course on Watts. This University has also created Watts academic chair.