Biography of Joshua Lederberg

Joshua Lederberg – American molecular biologist.

Name: Joshua Lederberg

Date of Birth: May 23, 1925

Place of Birth: Montclair, New Jersey, United States

Date of Death: February 2, 2008 (aged 82)

Place of Death: New York City, New York, United States

Occupation: Biologists

Father: Rabbi Zvi Hirsch Lederberg

Mother: Esther Goldenbaum Schulman

Spouse/Ex: Esther Miriam Zimmer (m. 1946-1966; divorced), Marguerite Stein Kirsch (m. 1968-2008)

Children: Anne Lederberg, David Kirsch (stepson)

Early Life

An American geneticist, pioneer in the field of bacterial genetics, who shared the 1958 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine (with George W. Beadle and Edward L. Tatum) for discovering the mechanisms of genetic recombination in bacteria, Joshua Lederberg was born on May 23, 1925, in Montclair, New Jersey, U.S. to a Jewish family, son of Esther Goldenbaum Schulman Lederberg and Rabbi Zvi Hirsch Lederberg.

Born in New Jersey, Lederberg initially wanted to acquire a medical degree. However, from his childhood, he had a natural aptitude for research work and while working for his medical degree at the Columbia University he began to experiment with the bread mold ‘Neurospora crassa’ under the mentorship of Francis Ryan. He soon realized that experimenting was more interesting than his medical studies and after two years at the medical school he took leave to join Edward L. Tatum to work on bacterial conjugation at the University of Stanford. Soon he established that E-coli bacteria can also reproduce sexually and was awarded Nobel Prize for this discovery at the age of thirty-three. He later established that genetic material could be moved from one strain of the bacterium Salmonella typhimurium to another using bacteriophage as an intermediary step. His works in this field established bacteria as a tool of genetic research.

In the period just preceding and following World War II, however, geneticists’ attention began to shift to an investigation of the structure and function of genes themselves. Higher organisms being less suitable for such studies, geneticists turned to much simpler forms such as bacteria and viruses. As a pioneer in this new line of research, Joshua Lederberg’s studies on both bacteria and viruses paved the way for the modern-day understanding of the chemical and molecular bases of genetics.

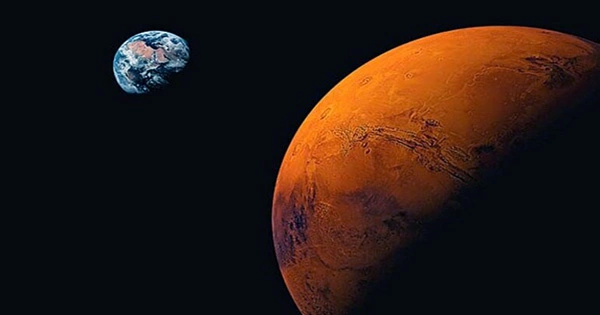

In addition to his contributions to biology, Lederberg did extensive research in artificial intelligence. This included work in the NASA experimental programs seeking life on Mars and the chemistry expert system Dendral.

Childhood, Family and Educational Life

An American molecular biologist, Joshua Lederberg was born on May 23, 1925, in Montclair, New Jersey, U.S. His father, Zwi H. Lederberg, was a Rabbi. His mother, Esther nee Goldenbaum, migrated from Palestine just two years prior to his birth. He was the eldest of his parent’s three sons. When Joshua was six months old, the family moved to New York City and settled down in Washington Heights, a neighborhood in the borough of Manhattan.

Lederberg began his schooling at Public School 46 and later shifted to Junior High School 164. He graduated from Stuyvesant High School in New York City at the age of 15 in 1941. While at school, Lederberg was allowed to conduct research in cytochemistry after school hours through American Institute Science Laboratory program. Works of H.G. Wells, Bernard Jaffe, and Paul De Kruif also influenced him a lot.

Lederberg enrolled in Columbia University in 1941, majoring in zoology. Under the mentorship of Francis J. Ryan, he conducted biochemical and genetic studies on the bread mold Neurospora crassa. Intending to receive his MD and fulfill his military service obligations, Lederberg worked as a hospital corpsman during 1943 in the clinical pathology laboratory at St. Albans Naval Hospital, where he examined sailors’ blood and stool samples for malaria.

Subsequently, Lederberg earned his bachelor’s degree in 1944 and entered the Columbia College of Physicians and Surgeons for his medical degree. At the same time, he continued with his experiments. However, once Oswald Avery published his paper on DNA, Lederberg’s aim in life took a different direction.

Personal Life

On 13, 1946, Joshua Lederberg married fellow scientist Esther Miriam Zimmer, who later became a noted microbiologist and a pioneer in bacterial genetics. For twenty years they worked together in different projects. However, personal competition slowly drove them apart and the couple divorced in 1966.

Lederberg married psychiatrist Marguerite Stein Kirsch in 1968. The couple had a daughter named Anne Lederberg. Lederberg also had a stepson, David Kirsch, from Marguerite’s previous marriage. The couple remained married until his death.

While Joshua Lederberg was a student of Edward L. Tatum his first wife Esther obtained her postgraduate degree at Stanford under George W. Beadles.

Career and Works

In 1941 Joshua Lederberg received a tuition scholarship from the Hayden Trust in order to afford the university. Serving as a laboratory assistant to Professor F. J. Ryan of the Zoology Department, Lederberg carried out several experiments on the mutation of the bread mold Neurospora, just then becoming an important organism for the study of biochemical genetics (that is, how genes control biochemical reactions in cells). After receiving his B.A. with honors in 1944, at the age of 19, Lederberg entered the College of Physicians and Surgeons at Columbia University to pursue a medical career.

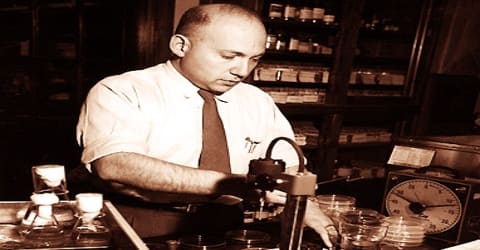

Lederberg had an idea that bacteria passed down an exact copy of genetic information and consequently, all cells in the lineage became its clone. He now began to work on that at Columbia University. His work caught the attention of his mentor Francis Ryan, who recommended him to Edward L. Tatum. Tatum was then working at the University of Yale on bacteria. He invited Lederberg to join his laboratory. Subsequently, Lederberg took one year’s leave from Columbia University and joined Tatum at Yale in March 1946. Here he was supported by Jane Coffin Childs Fund.

Lederberg and Tatum showed that the bacterium Escherichia coli entered a sexual phase during which it could share genetic information through bacterial conjugation. With this discovery and some mapping of the E. coli chromosome, Lederberg was able to receive his Ph.D. from Yale University in 1947. Joshua married Esther Miriam Zimmer (herself a student of Edward Tatum) on December 13, 1946.

With Tatum Lederberg published “Gene Recombination in Escherichia coli” (1946), in which he reported that the mixing of two different strains of a bacterium resulted in genetic recombination between them and thus to a new, crossbred strain of the bacterium. Scientists had previously thought that bacteria only reproduced asexually i.e., by cells splitting in two; Lederberg and Tatum showed that they could also reproduce sexually and that bacterial genetic systems are similar to those of multicellular organisms.

After intensive research with an Escherichia coli bacterium, Lederberg and Tatum were able to establish that E-coli entered a sexual phase during which it could share genetic information through bacterial conjugation. In the same year, they published their findings in a paper titled, ‘Gene Recombination in Escherichia coli’. As his one year leave from the Columbia University came to an end Lederberg decided not to return. Instead, he decided to remain at Yale and earn his Ph.D., receiving the degree in 1948.

Instead of returning to Columbia to finish his medical degree, Lederberg chose to accept an offer of an assistant professorship in genetics at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. His wife Esther Lederberg went with him to Wisconsin. She received her doctorate there in 1950. Meanwhile, in 1947, he was appointed as an Assistant Professor of Genetics at the University of Wisconsin.

In 1950, Lederberg was promoted to the post of Associate Professor and became a full Professor in 1954. Concurrently, Lederberg continued his research on bacteria and in 1952, made another astonishing discovery in collaboration with his graduate student Norton D. Zinder. In a paper titled ‘Genetic Exchange in Salmonella’, they revealed a second process of gene exchange between bacteria. They showed that a bacteria-infecting virus, known as a bacteriophage, acting as a carrier agent could transfer a bacterial gene from one bacterium to another. It first infects one bacterial cell and then reproduces itself inside using the bacteria’s cell machinery.

While biologists who had not previously believed that “sex” existed in bacteria such as E. coli were still confirming Lederberg’s discovery, he and his student Norton D. Zinder reported another and equally surprising finding. In the paper “Genetic Exchange in Salmonella” (1952), they revealed that certain bacteriophages (bacteria-infecting viruses) were capable of carrying a bacterial gene from one bacterium to another, a phenomenon they termed transduction.

Next in 1956, Joshua Lederberg, with Laurance Morse and Esther Lederberg, discovered specialized transduction. Later, he developed the technique of bacterial replica plating. It allowed bacterial colonies to be duplicated for further study. In 1956, the Society of Illinois Bacteriologists simultaneously awarded Joshua Lederberg and Esther Lederberg the Pasteur Medal, for “their outstanding contributions to the fields of microbiology and genetics”.

In 1957, Lederberg founded the Department of Medical Genetics at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. He has held visiting professorship in Bacteriology at the University of California, Berkeley in summer 1950 and University of Melbourne (1957). Also in 1957, he was elected to the National Academy of Sciences. Two years later, in 1959, Lederberg assumed the chairmanship of the newly formed Department of Genetics at Stanford University Medical School in Palo Alto, California.

Later in 1962, Lederberg became Director of the Kennedy Laboratories for Molecular Medicine in the same institute and served in that capacity until 1978. Sometime during this period, he collaborated with Australian virologist Frank Macfarlane Burnet to study viral antibodies. From the middle of the 1960s, he also began to take a keen interest in artificial intelligence and helped to develop Dendral (a pioneer project in artificial intelligence) along with Edward Feigenbaum, Bruce G. Buchanan, and Carl Djerassi.

In 1978, Lederberg became the president of Rockefeller University, until he stepped down in 1990 and became professor-emeritus of molecular genetics and informatics at Rockefeller University, reflecting his extensive research and publications in these disciplines. Throughout his career, Lederberg was active as a scientific advisor to the U.S. government. Starting in 1950, he was a member of various panels of the Presidential Science Advisory Committee.

Lederberg’s discoveries greatly increased the utility of bacteria as a tool in genetics research, and it soon became as important as the fruit fly Drosophila and the bread mold Neurospora. Moreover, his discovery of transduction provided the first hint that genes could be inserted into cells. The realization that the genetic material of living things could be directly manipulated eventually bore fruit in the field of genetic engineering, or recombinant DNA technology. At the dawn of space exploration, Lederberg coined the term exobiology to describe the scientific study of life outside Earth’s atmosphere. He later served as a consultant to NASA’s Viking mission to Mars.

In 1979, Lederberg became a member of the U.S. Defense Science Board and the chairman of President Jimmy Carter’s President’s Cancer Panel. In 1989, he received National Medal of Science for his contributions to the scientific world. In 1994, he headed the Department of Defense’s Task Force on Persian Gulf War Health Effects, which investigated Gulf War Syndrome. In the summer of 1997, Lederberg was studying the deadly 1918 flu virus, found in preserved tissue, in an attempt to find a vaccine against the disease that killed over 20 million people in Europe alone.

Awards and Honor

In 1956, Joshua Lederberg and Esther Lederberg were awarded the Pasteur Medal, for “their outstanding contributions to the fields of microbiology and genetics” by the Society of Illinois Bacteriologists.

In 1958, Joshua Lederberg received the Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine “for his discoveries concerning genetic recombination and the organization of the genetic material of bacteria”. He was only thirty-three years old then.

Death and Legacy

Joshua Lederberg died on February 2, 2008, in New York City, New York, U.S. He was survived by Marguerite, their daughter, Anne Lederberg, and his stepson, David Kirsch.

Lederberg is best remembered for his work on bacterium Escherichia coli. Earlier scientists were of the opinion that bacteria could only reproduce asexually; i.e. by splitting itself into two. Lederberg worked with Edward Tatum to show that E-coli could also reproduce sexually. He is also remembered for his work on a phenomenon now known as transduction. In 1952, he along with Norton D. Zinder showed that bacterial gene could be transferred from one bacterium to another by means of a virus called bacteriophage.

While Lederberg was made very aware throughout his life of the stiffness of personal competition, he remained firm in his belief that scientific discoveries, no matter how slight, were beneficial to the world. “The shared interests of scientists in the pursuit of universal truth,” Lederberg said in The Excitement and Fascination of Science, “remain among the rare bonds that can transcend bitter personal, national, ethnic, and sectarian rivalries.”

His work on astrobiology is also quite significant. When Sputnik was launched in 1957, it was Lederberg who cautioned that extraterrestrial microbes may gain entry into earth’s atmosphere onboard the spacecraft. He suggested that spacemen, as well as spacecraft, should be quarantined on return to earth and checked for such microbes.

In 2012, a large impact crater with a diameter of an 87 km in Xanthe Terra on the surface of Mars has been named after Lederberg.

Information Source: