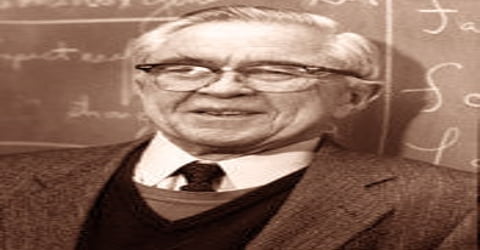

Biography of Edward B. Lewis

Edward B. Lewis – American geneticist.

Name: Edward Butts Lewis

Date of Birth: May 20, 1918

Place of Birth: Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, United States

Date of Death: July 21, 2004 (aged 86)

Place of Death: Pasadena, California, United States

Occupation: Geneticists

Father: Edward Butts Lewis

Mother: Laura Mary Lewis

Spouse/Ex: Pamela Harrah

Children: Hugh, Glenn, and Keith

Early Life

An American developmental geneticist who, along with geneticists Christiane Nüsslein-Volhard and Eric F. Wieschaus, was awarded the 1995 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine for discovering the functions that control early embryonic development, Edward B. Lewis was born on May 20, 1918, in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, U.S. the second son of Laura Mary Lewis (née Histed) and Edward Butts Lewis, a watchmaker-jeweler.

A youthful obsession with a simple insect led Edward B. Lewis to become one of the key scientists who deciphered the genetic code that forms all living beings. Lewis used the fruit fly to show how genes control an embryo’s development, and researchers have since shown that his discovery holds true in almost every animal, including humans.

Born in the early twentieth century, his childhood, as well as youth, was spent under financial paucity because his watchmaker-jeweler father lost his job at the start of the Great Depression. Yet it could not rob him of his energy, wit, and inquisitiveness. He started working with Drosophila while in school. Later he earned his bachelor’s degree in biostatistics from the University of Minnesota and his Ph.D. in Genetics from Caltech. During this period, he also invented the ‘cis-trans’ test, which is still taught in the introductory undergraduate biological courses. However, Lewis could begin his actual research works only after returning to Caltech after brief war service. He mostly worked on genetics and it earned him a number of awards including the Nobel Prize. Equally significant was his study on the effects of radiation on human health. He fought to establish that even low level of radiation is bad for health. Although short in stature, he was great in all kinds of human quality and was greatly respected for his modesty, personal integrity, and intellect.

Childhood, Family and Educational Life

Edward B. Lewis, in full Edward Butts Lewis, was born on May 20, 1918, in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania. His father, also Edward Butts Lewis, worked in a jewelry store as watchmaker-jeweler. When in 1929, the Great Depression set in, he lost his job and the family had to face tremendous economic hardship. In spite of that, Edward’s mother, Laura Mary Lewis (née Histed), always encouraged her children to study. His only brother, James Lewis, was five and a half years older to him. They also had a sister, Mary Louise Lewis, who died the night before James was born.

Lewis began his work on fruit flies as a high school sophomore, when he and a friend spent the school biology club’s entire treasury, $4, responding to an ad in Science magazine selling fruit flies at the rate of 100 for $1. Fruit flies are easy creatures to study because they breed easily, have a simple structure, and go from eggs to mature flies in only ten days. Lewis and his friend would visit a school lab every day to look through newly hatched flies with a magnifying glass, searching for mutants, the keys to biology research. One mutant they found, called “held-out,” is still used in genetics research.

Edward had his early education at Elmer L. Meyers Junior/Senior High School. While studying there he developed an interest in biology and was especially interested in toads and snakes. Once his mother found a rattlesnake in his cupboard; he had kept it there because he was yet to build a terrarium for it. During this period, he also paid a regular visit to the Wilkes-Barre’s Osterhout Public Library.

Lewis’s interest in genetics was kindled in high school. He studied biostatistics at the University of Minnesota (B.A., 1939) and genetics at the California Institute of Technology (Ph.D., 1942), where he taught from 1946 to 1988. He completes a master’s degree in meteorology in 1943. Thereafter, he spent World War II years, serving as a meteorologist and oceanographer in the U.S. Air Force.

Personal Life

Edward Butts Lewis met Pamela Harrah, in 1946. She was a Stanford graduate, who joined Caltech as stock-keeper of the Caltech Drosophila Stock Center on the invitation of George W. Beadle. She was also an accomplished artist whose paintings would always have insects in them.

Edward and Pamela got married a few months after their meeting and remained together until his death. They had three sons; Hugh, Glenn, and Keith. Among them, Glen has passed away. Hugh is now an attorney at Bellingham and Keith is a biology research assistant at Berkeley.

Since Lewis’s father’s name was also Edward Butts Lewis, his full name was meant to be Edward Butts Lewis Junior. But while filling up the birth certificate form, his parents forgot to add Junior and so he too remained as Edward Butts Lewis.

Lewis was famous on campus for the costumes he wore to the school’s Halloween party; once, he came dressed as a mutant fruit fly with two tails. Lewis’ schedule at Caltech remained the same until a few months before his death: he got to his office at 8 a.m. and often worked until midnight, with breaks to practice the flute from 10 to 10:30, swim in the pool, and take a mid-afternoon nap.

Career and Works

In 1946, on being released from the military service, Edward Lewis joined California Institute of Technology as an instructor in the Biology Division. In the same year, he was given the responsibility for supervising the extensive Caltech Drosophila Stock Center and began working with them. Lewis returned to Caltech in 1946, spent a year as a fellow at Cambridge University in Britain from 1947 to 1948, then spent the rest of his career at Caltech.

After the war, Lewis returned to his studies of the fruit fly. One of his supervisors, Thomas Hunt Morgan, had used fruit flies to help prove that chromosomes carry genes, which hold hereditary characteristics, a discovery that won him the Nobel Prize in 1933. But when Lewis began his work, scientists did not know much more than that about how genes worked. On coming back to the U.S.A, he rejoined Caltech as an Assistant Professor of Biology and served in that capacity from 1948 to 1949.

In 1949, Lewis was promoted to the post of the Associate Professor of Biology. He soon discovered that the bithorax family of mutants was actually a cluster of genes. Eventually, he called them the bithorax gene complex.

Lewis reached a breakthrough when he bred two mutant flies and produced flies with four wings instead of two. That meant that a whole section of the fly’s thorax had been replaced with a duplicate of the section next to it. Not only had a mutant gene caused the change, Lewis realized, but the gene must have controlled the activity of other genes to produce the second wing. For decades, Lewis bred mutant fruit flies, until he finally identified the genes that controlled the development of each section of the fly. He surprised other scientists by showing that the genes’ code was simple: the genes that control early development of the fly embryo (called homeotic genes) lined up on the chromosomes in order, just as the segments they controlled appear on the fly. That order, which scientists call the “colinearity principle,” was later proven to be true in humans, mice, and other vertebrates. Lewis’ work on homeotic genes, summarized in a major article in 1978, won him the 1995 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine.

“It was as if he made evolution occur in real time,” Dr. Gerald R. Fink, a professor of genetics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, told the New York Times. “Ed Lewis worked to use genetics to show profound evolutionary strategies. There is no more remarkable evidence of that than his fruit fly with four wings.”

During the 1950s, Lewis studied the effects of radiation from X-rays, nuclear fallout and other sources as possible causes of cancer. He reviewed medical records from survivors of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, as well as radiologists and patients exposed to X-rays. Lewis concluded that “health risks from radiation had been underestimated”. Lewis published articles in Science and other journals and made a presentation to a Congressional committee on atomic energy in 1957.

In 1956, Lewis became a full Professor of Biology, remaining in the post till 1966. Meanwhile, from the middle of the 1950s, he started a study on the effects nuclear tests, X-rays and other sources of radiations on human health.

At the scientific level of the debate, the crucial question was whether the “threshold theory” was valid or whether, as Lewis insisted, the effects of radioactivity were “linear with no threshold”, where every exposure to radiation had a long-term cumulative effect. The issue of linearity versus threshold re-entered the debate on nuclear fallout in 1962, when Ernest Sternglass, a Pittsburgh physicist, argued that the linearity thesis was confirmed by the research of Alice Stewart.

Finally, in 1957, Lewis published a comprehensive paper on it, titled ‘Leukemia and Ionizing Radiation’. In this paper, he not only calculated the increased risk of leukemia from radiation but also declared that “health risks from radiation had been underestimated”. His findings were challenged by nuclear scientists who claimed low doses of radiation did not do any harm. Ultimately, his points prevailed. Soon after this, Lewis resumed his study on genetics. In 1964, working with Drosophila, he established the connection between the arrangements of genes on the chromosome to specific body segments. Much later, it was established that such genetic layout was common across animal species.

In 1966, Lewis became the Thomas Hunt Morgan Professor of Biology at Caltech, remaining in this position till 1988. Meanwhile, from 1975-76, he was also the Visiting Professor, Institute of Genetics, University of Copenhagen, Denmark. In 1982, Lewis identified the gene clusters, important for early embryonic development and referred to them as ‘master control’. Subsequently, he also identified the corresponding genes in humans.

Lewis remained a biology professor at Caltech until his 1988 and stayed active at the school as a professor emeritus after his retirement. He provided the entertainment at the Caltech dinner in honor of his Nobel prize in 1995, playing with a chamber music group in the lobby as guests arrived. He was famous on campus for the costumes he wore to the school’s Halloween party; once, he came dressed as a mutant fruit fly with two tails. Lewis’ schedule at Caltech remained the same until a few months before his death: he got to his office at 8 a.m. and often worked until midnight, with breaks to practice the flute from 10 to 10:30, swim in the pool, and take a mid-afternoon nap.

On November 20, 2001, Lewis was interviewed by Elliot Meyerowitz in the Kerckhoff Library at the California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, California. This interview was released on DVD in 2004 as “Conversations in Genetics: Volume 1, No. 3 – Edward B. Lewis; An Oral History of Our Intellectual Heritage in Genetics” 67 min; Producer Rochelle Easton Esposito; The Genetics Society of America.

Awards and Honor

Edward B. Lewis was elected to the National Academy of Sciences in 1968 and received the National Medal of Science in 1990.

Lewis received numerous awards and honors during his career including the Thomas Hunt Morgan Medal in 1983, the Louisa Gross Horwitz Prize in 1992, and the Albert Lasker Award for Basic Medical Research in 1991.

In 1989, Lewis became a Foreign Member of the Royal Society, London. Other than that, he was also a member of many other societies at home and abroad such as the National Academy of Sciences, the Genetics Society of America, and the American Philosophical Society, etc.

In 1995, Edward B. Lewis received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his “discoveries concerning the genetic control of early embryonic development”. He shared the prize with Christiane Nüsslein-Volhard and Eric F. Wieschaus, who independently worked on the same topic.

Death and Legacy

Edward Butts Lewis died of prostate cancer on July 21, 2004, in Pasadena, California, U.S.; he was 86. He is survived by his wife, Pamela, an artist he met in the Caltech laboratory, and their sons, Hugh and Keith. A third son died in 1965.

Edward B. Lewis is best remembered for his discovery of Drosophila Bithorax gene complex and illumination of its function. He also established that genes are arranged according to the colinearity principle, which means they appear in the same order as their corresponding body segments. He explained that the first set of genes controls the functions of head and thorax; the middle set controls the functions of abdomen, and the last set controls the functions of the posterior section.

Lewis also pointed out this genetic functions may overlap and this he established with the creation of a mutant fly with four wings. His work with Drosophila laid the foundation of developmental genetics. It also helped scientists to understand the reason behind different types of deformities, both in humans and higher animals.

Information Source: