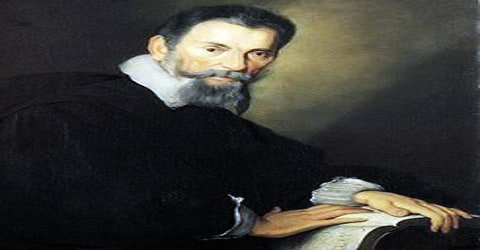

Biography of Claudio Monteverdi

Claudio Monteverdi – Italian composer, string player, and choirmaster.

Name: Claudio Giovanni Antonio Monteverdi

Date of Birth: May 15, 1567

Place of Birth: Cremona, Italy

Date of Death: November 29, 1643 (age 76)

Place of Death: Republic of Venice

Occupation: Composer

Father: Baldassare Monteverdi

Mother: Maddalena (née Zignani)

Spouse/Ex: Claudia de Cattaneo (m. 1599-died 1607)

Children: Francesco, Massimiliano, and Leonora

Early Life

Italian composer in the late Renaissance, the most important developer of the then new genre, the opera, Claudio Monteverdi was born on May 15, 1567, in Cremona, Lombardy (that’s a historic region in Italy). A composer of both secular and sacred music, and a pioneer in the development of opera, he is considered a crucial transitional figure between the Renaissance and the Baroque periods of music history. Monteverdi basically invented the opera, and his other secular pieces, especially his madrigals, were hugely influential on the developing Baroque style. His sacred music was equally important, and he showed adaptability to the desires of his clientele (his patrons). For instance, his ‘Vespers for the Blessed Virgin Mary’ was incredibly progressive, while his 6-voice mass written for the papal service in Rome was in the traditional, Renaissance style. It is this adaptability that makes his music so influential: he was both immensely popular in his time, owing to his capacity as a Renaissance composer, yet avant-garde as well.

Born in the middle of the sixteenth century in the Lombardy region of Italy, he studied music with Marc’Antonio Ingegneri, the maestro at the local cathedral. Monteverdi started writing both religious and secular music early in his life, publishing his first work at the age of 15. Around the age of 22, he started his career as a string player at the Court of Mantua, being appointed to the position of the maestro di capella at the age of 35. Later, he moved to Venice, where he was appointed to the same post at the St. Mark’s. Remaining there till his death, he wrote much religious as well as secular music, also introducing secular elements into church music. ‘La favola d’Orfeo’, one of his first operas, is being regularly performed till now. He also did much to bring a “modern” secular spirit into church music.

While Monteverdi worked extensively in the tradition of earlier Renaissance polyphony, such as in his madrigals, he undertook great developments in form and melody and began to employ the basso continuo technique, distinctive of the Baroque. No stranger to controversy, he defended his sometimes novel techniques as elements of a seconda pratica, contrasting with the more orthodox earlier style which he termed the prima pratica. Largely forgotten during the eighteenth and much of the nineteenth centuries, his works enjoyed a rediscovery around the beginning of the twentieth century. He is now established both as a significant influence in European musical history and as a composer whose works are regularly performed and recorded.

Childhood, Family and Educational Life

Claudio Monteverdi, in full Claudio Giovanni Antonio Monteverdi (Italian: ˈklaudjo monteˈverdi), was born in 1567 in Cremona, Lombardy, Italy. Although the exact date of his birth is not known, the records at the church of SS Nazaro e Celso, Cremona states that he was baptized on 15 May 1567 as Claudio Zuan Antonio. He was the first child of the apothecary Baldassare Monteverdi and his first wife Maddalena (née Zignani). At the time of his birth, Cremona was under the administration of Milan. But because Milan was assigned to Spain under the 1513 Treaty of Noyon he was technically born a Spanish citizen. However, he always considered himself an Italian. Claudio’s brother Giulio Cesare Monteverdi (b. 1573) was also to become a musician.

There is no clear record of Monteverdi’s early musical training or evidence that (as is sometimes claimed) he was a member of the Cathedral choir or studied at Cremona University. His first teacher was Marc’Antonio Ingegneri, at the Cathedral of Cremona. This began Monteverdi’s exposure to liturgical music, especially vocal/choral music.

Claudio Monteverdi lost his mother when he was eight or nine years old. By then, Baldassare Monteverdi had made a modest move up the social ladder. In 1576 or 1577, he took a second wife, Giovanna Gadio, fathering three more children with her. But she too died early. His father next married Francesca Como, but this marriage was childless. In spite of having to adjust to two stepmothers, Claudio remained emotionally close to his father, feeling empathy for his father’s repeated losses. It would one day have an effect on many of his compositions.

Monteverdi’s first published work, a set of motets, Sacrae cantiunculae (Sacred Songs) for three voices, was issued in Venice in 1582 when he was only fifteen years old. Entitled ‘Sacrae cantiunculae’, it was followed by ‘Madrigali spirituali’, printed in 1583 from Brescia. In this, and his other initial publications, he describes himself as the pupil of Marc’Antonio Ingegneri, who was from 1581 (and possibly from 1576) to 1592 the maestro di cappella at Cremona Cathedral. The musicologist Tim Carter deduces that Ingegneri “gave him a solid grounding in counterpoint and composition”, and that Monteverdi would also have studied playing instruments of the viol family and singing.

Personal Life

In 1599, Claudio Monteverdi married Claudia de Cattaneo, a singer at the Court of Duke Vincenzo I Gonzaga of Mantua. They had three children; two sons named Francesco and Massimiliano and a daughter, Leonora, who died soon after her birth. His wife, singer Claudia Cattaneo, died in 1607, and in 1632 he became a priest.

Career and Works

Claudio Monteverdi began his career in music early in his life. At the time of publication of ‘Sacrae cantiunculae’, he was barely 15 years old. Thereafter, he continued writing and by the time he was 20, he had a number of works, both religious and secular, in print.

Monteverdi’s first publications also give evidence of his connections beyond Cremona, even in his early years. His second published work, Madrigali spirituali (Spiritual Madrigals, 1583), was printed at Brescia. His next works (his first published secular compositions) were sets of five-part madrigals, according to his biographer Paolo Fabbri “the inevitable proving ground for any composer of the second half of the sixteenth century … the secular genre par excellence”. The first book of madrigals (Venice, 1587) was dedicated to Count Marco Verità of Verona; the second book of madrigals (Venice, 1590) was dedicated to the President of the Senate of Milan, Giacomo Ricardi, for whom he had played the viola da braccio in 1587.

In 1587, in order to secure the patronage of Marco Verita, the Count of Verona, Monteverdi dedicated his ‘First Book of Madrigals’ to him; but it failed to achieve its objective. In the same year, he played ‘viola da braccio’ for Giacomo Ricardi, the President of the Senate of Milan. In 1589, he left Cremona to become a strong player in the Court of Duke Vincenzo I Gonzaga of Mantua. At that time, the Duke was trying to establish his court as a center for music, appointing noted musicians from across Europe as his court musicians. It was an ideal place to learn and young Monteverdi greatly benefitted from such association, observing and later participating in the theatrical activities in the court. He was especially influenced by the Flemish musician Giaches de Wert, the maestro di capella at the court.

It is not known exactly when Monteverdi left his hometown, but he entered the employ of the duke of Mantua about 1590 as a string player. He immediately came into contact with some of the finest musicians, both performers and composers, of the time. The composer who influenced him the most seems to have been the Flemish composer Giaches de Wert, a modernist who, although no longer a young man, was still in the middle of an avant-garde movement in the 1590s. The crux of his style was that music must exactly match the mood of the verse and that the natural declamation of the words must be carefully followed. Since Wert chose to use the highly concentrated, emotional lyric poetry of Tasso and Tasso’s rival Battista Guarini, Wert’s music also became highly emotional, if unmelodious and difficult to sing.

In 1590, Monteverdi had his ‘Second Book of Madrigals’ published from Venice. He dedicated the work to Giacomo Ricardi of Milan, perhaps indicating he was still looking for permanent position. But soon after that, the situation became more stable. By the early 1590s, Monteverdi was able to establish his position at Mantua. When in 1592, he had ‘Third Book of Madrigals’ published, he dedicated the work to the Duke Vincenzo I Gonzaga. Thereafter for the next eleven years, he published very little. However, he continued to compose. In 1595, Monteverdi accompanied the Duke on his military campaigns to Hungary. Once again in 1599, he was a part of the Duke’s entourage to Flanders, where he became acquainted with the French school of contemporary music. Later in 1600, he possibly accompanied the Duke on his trip to Florence.

Monteverdi’s compositions from the Mantuan period betray the influence of Giaches de Wert, who Monteverdi eventually succeeded as the maestro di cappella. It was around this time that Monteverdi’s name became widely known, due largely to the criticism levied at him by G.M. Artusi in his famous 1600 treatise “on the imperfection of modern music.” Artusi found Monteverdi’s contrapuntal unorthodoxies unacceptable and cited several excerpts from his madrigals as examples of modern musical decadence. In the response that appeared in the preface to Monteverdi’s fifth book of madrigals, the composer coined a pair of terms inextricably tied to the diversity of musical taste that came to characterize the times. He referred to the older style of composition, in which the traditional rules of counterpoint superseded expressive considerations, as the prima prattica. The seconda prattica, as characterized by such works as Crudi Amarilli, sought to put music in the servitude of the text by whatever means necessary-including “incorrect” counterpoint-to vividly express the text.

At the turn of the 17th century, Monteverdi found himself the target of musical controversy. The influential Bolognese theorist Giovanni Maria Artusi attacked Monteverdi’s music (without naming the composer) in his work L’Artusi, overo Delle imperfettioni della moderna musica (Artusi, or On the imperfections of modern music) of 1600, followed by a sequel in 1603. Artusi cited extracts from Monteverdi’s works not yet published (they later formed parts of his fourth and fifth books of madrigals of 1603 and 1605), condemning their use of harmony and their innovations in the use of musical modes, compared to the orthodox polyphonic practice of the sixteenth century.

Although Monteverdi still followed the meaning of the verse he often used intense and prolonged dissonance, which invited criticism from the more conservative musicians, chiefly Giovanni Maria Artusi, who attacked him in a series of pamphlets. Although initially, Monteverdi was reluctant to reply he later made an important statement on the nature of his work. In it, he said that he was merely following a tradition that had been developing over a period of fifty years, which sought to create a union between words and music. The debate had a positive effect on his popularity, establishing him as a composer even outside northern Italy. Very soon, he became famous for his exquisite miniature works.

Some of his madrigals were published in Copenhagen in 1605 and 1606, and the poet Tommaso Stigliani published a eulogy of him in his 1605 poem “O sirene de’ fiumi”. The composer of madrigal comedies and theorist Adriano Banchieri wrote in 1609: “I must not neglect to mention the most noble of composers, Monteverdi … his expressive qualities are truly deserving of the highest commendation, and we find in them countless examples of matchless declamation … enhanced by comparable harmonies.” The modern music historian Massimo Ossi has placed the Artusi issue in the context of Monteverdi’s artistic development: “If the controversy seems to define Monteverdi’s historical position, it also seems to have been about stylistic developments that by 1600 Monteverdi had already outgrown”.

In 1607, Monteverdi’s first opera (and the oldest to grace modern stages with any frequency) L’Orfeo, was performed in Mantua. This was followed in 1608 by L’Arianna, which, despite its popularity at the time, no longer survives except in libretti, and in the title character’s famous lament, a polyphonic arrangement of which appeared in his sixth book of madrigals (1614). Disagreements with the Gonzaga court led him to seek work elsewhere, and finally, in 1612, he was appointed maestro di cappella at St. Mark’s Cathedral in Venice.

A few months after the production of Orfeo, Monteverdi suffered the loss of his wife, seemingly after a long illness. He retired in a state of deep depression to his father’s home at Cremona, but he was summoned back to Mantua almost immediately to compose a new opera as part of the celebrations on the occasion of the marriage of the heir to the duchy, Francesco Gonzaga, to Margaret of Savoy. Monteverdi returned unwillingly and was promptly submerged in a massive amount of work. He composed not only an opera but also ballet and music for an intermezzo to a play.

The hard work affected his health and in 1608, Monteverdi returned to Cremona, asking for an honorable dismissal. Increasingly poor remunerations were another reason for it. When his request was turned down and his remuneration was raised, he unwillingly returned to Mantua. Once in Mantua, he started looking for an alternative position; but unhappy that he was, he did not remain unproductive. However, his works during this period reflected his deep depression. Among his works during this period, most significant was ‘Vesperis in Festis Beata Mariae Vergine’ (1610).

Duke Vincenzo died on 18 February 1612. When Francesco succeeded him, court intrigues and cost-cutting led to the dismissal of Monteverdi and his brother Giulio Cesare, who both returned, almost penniless, to Cremona. Despite Francesco’s own death from smallpox in December 1612, Monteverdi was unable to return to favor with his successor, his brother Cardinal Ferdinando Gonzaga. In 1613, following the death of Giulio Cesare Martinengo, Monteverdi auditioned for his post as maestro at the Basilica of San Marco in Venice, for which he submitted music for a Mass. He was appointed in August 1613 and given 50 ducats for his expenses (of which he was robbed, together with his other belongings, by highwaymen at Sanguinetto on his return to Cremona).

Although Monteverdi was not a church musician, he took up his duties seriously, completely revitalizing music at the basilica, which had been declining since 1609. He held regular choral services and hired the best musicians. Among them were would-be famous composers like Francesco Cavalli and Alessandro Grandi. In 1616 Monteverdi composed the ballet Tirsi i Clori for Ferdinand of Mantua, the more-favored brother of his deceased and disliked ex-employer. The following years saw some abandoned operatic ventures, the now-lost opera La finta pazza Licori, and the dramatic dialogue Combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda. He also wrote a lot of church music, which included among other pieces, two Masses, two Magnificats, a litany, dozens of psalm settings. In 1640, he published some of them in ‘Selva morale e spirituale’ while the rest were published posthumously in 1650. Concurrently, he also continued to write secular music.

Monteverdi, however, was increasingly concerned with the expression of human emotions and the creation of recognizable human beings, with their changes of mind and mood. Thus, he wished to develop a greater variety of musical means, and in his seventh book of madrigals (1619), he experimented with many new devices. Most were borrowed from the current practices of his younger contemporaries, but all were endowed with greater power. There are the conversational “musical letters,” deliberately written in a severe recitative melody in an attempt to match the words. The ballet Tirsi e Clori, written for Mantua in 1616, shows, on the contrary, a complete acceptance of the simple tunefulness of the modern aria.

Claudio Monteverdi published his ‘Sixth Book of Madrigals’ in 1614. It would be followed by two more books on Madrigals, to be published in 1619 and 1638 respectively. Meanwhile, he also renewed his contract with the Court at Mantua, writing a ballet ‘Tirsi e Clori’, for Ferdinand of Mantua in 1616. He also tried to write a few operas for the Court at Mantua, abandoning them in the midway. Instead, he concentrated on creating a practical philosophy of music, which found expression in his 1624 dramatic cantata, ‘Il combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda’ and 1627 comic opera, whose score is now lost. In this work, the rapid reiteration of single notes in strict rhythms and the use of pizzicato plucking strings to express the clashing of swords show important steps forward in the idiomatic use of stringed instruments. Monteverdi wrote a mass, and provided other musical entertainment, for the visit to Venice in 1625 of the Crown Prince Władysław of Poland, who may have sought to revive attempts made a few years previously to lure Monteverdi to Warsaw. He also provided chamber music for Wolfgang Wilhelm, Count Palatine of Neuburg, when the latter was paying an incognito visit to Venice in July 1625.

Monteverdi also received commissions from other Italian states and from their communities in Venice. These included, for the Milanese community in 1620, music for the Feast of St. Charles Borromeo, and for the Florentine community a Requiem Mass for Cosimo II de’ Medici (1621). Monteverdi acted on behalf of Paolo Giordano II, Duke of Bracciano, to arrange publication of works by the Cremona musician Francesco Petratti. Among Monteverdi’s private Venetian patrons was the nobleman Girolamo Mocenigo, at whose home was premiered in 1624 the dramatic entertainment Il combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda based on an episode from Torquato Tasso’s La Gerusalemme liberata. In 1627 Monteverdi received a major commission from Odoardo Farnese, Duke of Parma, for a series of works, and gained leave from the Procurators to spend time there during 1627 and 1628.

In 1630, plague broke out in Venice, leaving Monteverdi without commission. Sometimes now, he decided to take the Holy Order, being admitted to the tonsure in 1631. In November, as the epidemic was declared over, he wrote a grand mass for the thanksgiving service at San Marco. In 1632, he has ordained a deacon. In the same year, Monteverdi published his second set of Scherzi Musicali, the first set being published in 1607, when he was maestro at Mantua. Continuing to write both religious and secular music, he published a ballet entitled ‘Volgendo il ciel’ in 1637 and ‘Eighth Book of Madrigals’ in 1638. He was then 70 years old and his musical career was thought to be over by now. But it did not.

Though this collection, put together when Monteverdi was more than 70 years old, might seem the end of his career, chance played a part in inspiring him to an Indian summer of astonishing productivity: the first public opera houses opened in Venice in 1637. As the one indigenous composer with any real experience in the genre, he naturally was involved with them almost from the beginning. L’Arianna has revived again, and no fewer than four new operas were composed within about three years. Only two of them have survived in score The Return of Ulysses to His Country and The Coronation of Poppea and both are masterpieces. Although they still retain some elements of the Renaissance intermezzo and pastoral, they can be fairly described as the first modern operas.

Throughout his life, Monteverdi is believed to have written 18 operas and at least four of them in the early 1640s. However, among the four, only two survive to this day. ‘Il ritorno d’Ulisse in patria’, one of the surviving operas, was written for the carnival season of 1639-1640. Taken from the second half of Homer’s Odyssey, the libretto was written by Giacomo Badoaro. Today, it is considered as one of the first modern operas. The other surviving opera, entitled ‘L’incoronazione di Poppea’, was written for 1643 carnival. Written to the libretto by Giovanni Francesco Busenello, it was one of the first operas to use historical events, describing how Emperor Nero’s mistress, Poppaea, became the crowned princess.

The years 1640-1641 saw the publication of the extensive collection of church music, Selva morale e spirituale. Among other commissions, Monteverdi wrote music in 1637 and 1638 for Strozzi’s “Accademia degli Unisoni” in Venice, and in 1641 a ballet, La Vittoria d’Amore, for the court of Piacenza. He revised his earlier opera L’Arianna in 1640 and wrote three new works for the commercial stage, Il ritorno d’Ulisse in patria (The Return of Ulysses to his Homeland, 1640, first performed in Bologna with Venetian singers), Le nozze d’Enea e Lavinia (The Marriage of Aeneas and Lavinia, 1641, music now lost), and L’incoronazione di Poppea (The Coronation of Poppea, 1643). The introduction to the printed scenario of Le nozze d’Enea, by an unknown author, acknowledges that Monteverdi is to be credited for the rebirth of theatrical music and that “he will be sighed for in later ages, for his compositions will surely outlive the ravages of time.”

Monteverdi shows how the philosophy of music evolved during his early years in Venice could be put to use, using all the means available to a composer of the time, the fashionable arietta (i.e., a short aria), duets, and ensembles, and how they could be combined with the expressive and less fashionable recitative of the early part of the century. The emphasis is always on the drama: the musical units are rarely self-contained but are usually woven into a continual pattern, so that the music remains a means rather than an end. There is also a sense of looking toward the grand climax of the drama, which inspires a grand scena for one of the main singers, Ulisse, Nero, or Poppea. At the same time, there are enough memorable melodies for the opera to seem musically attractive. With these works Monteverdi proved himself to be one of the greatest musical dramatists of all time.

Death and Legacy

In his last surviving letter (20 August 1643), Claudio Monteverdi, already ill, was still hoping for the settlement of the long-disputed pension from Mantua and asked the Doge of Venice to intervene on his behalf. Monteverdi died in Venice on 29 November 1643, after paying a brief visit to Cremona and is buried in the Church of the Frari. He was survived by his sons; Masimilliano died in 1661, Francesco after 1677.

Today, Claudio Monteverdi is remembered as one of the important developers of opera music. ‘La favola d’Orfeo’, first performed in 1607, is probably his most popular work in this genre. It is also one of the earliest surviving operas, which is still being regularly performed.

Monteverdi’s music can be divided into two separate styles: sacred and secular. People can find elements of Renaissance polyphony in his early works, especially the early secular pieces. As he developed as a composer, Monteverdi began integrating elements of Italian monody. Where Renaissance music was wildly polyphonic, having ever increasing simultaneous melodic lines, the Italian monody style was an essential element of early Baroque music. In it, music was pared down to singular melodic line with an instrument accompanying, especially in vocal music. Monteverdi’s secular music can be further divided into two important types: madrigals and operas. That isn’t to say he didn’t compose anything else (he did compose a handful of motets); however, his secular music is almost entirely remembered for these types.

His unpublished religious works were posthumously published in 1650. In the following year, unpublished lighter pieces such as canzonettas, which he seemed to have written throughout his life, were published as ‘Ninth Book of Madrigals’.

Information Source: