Biography of Charles Nicolle

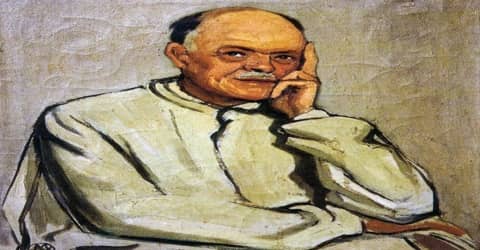

Charles Nicolle – French bacteriologist.

Name: Charles Jules Henry Nicolle

Date of Birth: 21 September 1866

Place of Birth: Rouen, France

Date of Death: 28 February 1936 (aged 69)

Place of Death: Tunis, Tunisia

Occupation: Bacteriologist

Father: Eugène Edouard Nicolle

Mother: Marie Louise Aline Louvrier

Spouse/Ex: Alice Avice

Children: Marcelle, Pierre

Early Life

A French bacteriologist who received the 1928 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine for his discovery (1909) that typhus is transmitted by the body louse, Charles Nicolle was born into a middle-class family in the city of Rouen, France on September 21, 1866. Nicolle made a further crucial contribution to infectious disease research when he discovered inapparent infections: these are cases where an individual is infected with a disease and spreads it without falling ill.

Born in Rouen, France, Nicolle studied medicine as his father wanted him to be a doctor. But soon after receiving his medical degree he was drawn to bacteriological research and within three years became head of the bacteriology laboratory at the Medical School of Rouen. Subsequently, he shifted to Tunisia to become Director of Pasteur Institute at Tunis. He turned the institute into a distinguished hub for bacteriological research and personally took up extensive research on different types of microbes. Among them, his research on epidemic typhus was most significant. He established that the vector of this disease, which killed thousands of people every winter, was none other than body louse and one can stay protected simply by getting rid of lice. After this de-lousing camps were regularly organized in Tunis. During World War I, delousing stations were also established on the Western Front, which helped to save thousands of lives. In addition, he had also worked on Malta fever, tick fever, cancer, scarlet fever, rinderpest, measles, influenza, tuberculosis, trachoma and had also discovered a new parasitic organism called Toxoplasma gondii.

Childhood, Family and Educational Life

Charles Nicolle, in full Charles-Jules-Henri Nicolle, was born on 21 September 1866 in Rouen, France. His mother was Marie Louise Aline Louvrier. His father was Eugène Edouard Nicolle, a university professor, and hospital doctor. The couple had three sons, all of whom enjoyed outstanding careers: Charles’s older brother Maurice became a renowned microbiologist, while his younger brother Marcel became an art critic, museum curator, and recipient of the French Legion of Honor.

Young Nicolle learned about biology early from his father Eugène Nicolle, a doctor at a Rouen hospital. He started his education at Lycée Pierre-Corneille de Rouen, where he received a classical education and was drawn towards literature, history, and arts.

Nicolle did not enjoy living in Rouen he considered it, and most of its citizens, dull and boring. He spent his spare time reading especially books that allowed his mind to wander far from his hometown: he loved travel books, history books, fairy stories, and Jules Verne’s’ fantasy stories. Despite his disdain for Rouen, at age 18, Charles Nicolle began studying medicine at its university’s medical school.

Nicolle acquired his medical degree in 1889 and obtained a medical internship at Hospice d’Ivry. Next, in 1890, Nicolle entered the Pasteur Institute and started working on his doctoral thesis under the guidance of Pierre Paul Émile Roux. Concurrently, he worked as a demonstrator in the microbiological section. In 1892, Nicolle attended a course on microbiology and on its completion he was promoted to the post of an assistant. Finally, he received his M. D. degree in 1893. His doctoral dissertation paper was titled ‘Recherches sur la chancre mou’ (Researches on the soft chancre).

Personal Life

In October 1895, age 29, Charles Nicolle married 21-year-old Alice Louise Avice. The couple had two children, a daughter named Marcelle born in 1896 and a son named Pierre born in 1898. Marcelle later grew up to be a doctor in Tunisia.

After leaving France in 1903, Charles Nicolle worked for the rest of his life as director of the Pasteur Institute in the city of Tunis. Unfortunately, the deafness that started when he was a young man grew progressively worse, making it increasingly difficult for Nicolle to enjoy any social life. He never lost his love of history and literature. He wrote a number of novels including The Two Thieves, The Pleasures of Boredom, and Marmouse and his Guests.

Career and Works

After obtaining his medical degree in Paris in 1893, Charles Nicolle returned to Rouen, where he became a member of the medical faculty and engaged in bacteriological research. In 1902 he was appointed the director of the Pasteur Institute in Tunis, and during his 31 years’ tenure in that post, the institute became a distinguished center for bacteriological research and for the production of serums and vaccines to combat infectious diseases. It was here he would make his great discoveries about epidemic typhus.

Nicolle had very little experience of this disease in France. Soon he was observing multiple cases in Tunisia, where the disease regularly broke out in rural areas in winter then spread to the city, particularly into prisons and flophouses. He made understanding typhus his top priority. Six months after he arrived in Tunis, Nicolle arranged to visit a prison to study typhus in the inmates. A day before the visit was scheduled he began coughing blood. Two of his colleagues went in his place. Nicolle recovered from whatever had made him cough blood. The two who visited the prison were less fortunate both died of typhus.

At the same time, Nicolle carried on extensive research on bacteriology. In 1903, he began his research on malaria and brucellosis and then in 1907, he started working on trachoma. Simultaneously, he also collaborated with local doctors on Mediterranean splenomegaly in children and recognized that Leishmania donovani is responsible for such disease. By 1910, he showed that dogs were the vector of this disease.

In Tunis, Nicolle noticed that typhus was very contagious outside the hospital, with sufferers of the disease-transmitting it to many people who came into contact with them. Once inside the hospital, however, these same patients ceased to be contagious. Nicolle suspected that the key point in this reversal was that of admission to the hospital when patients were bathed and their clothes were confiscated. The carrier of typhus must be in the patients’ clothes or on their skin and could be removed from the body by washing. The obvious candidate for the carrier was the body louse (Pediculus humanus humanus), which Nicolle proved to be the culprit in 1909 in a series of experiments involving monkeys.

In 1908, Nicolle discovered a new parasitic protozoan called Toxoplasma gondii along with L. Manceaux. They found it in the blood of gondi, a small rodent, native to South Tunisia. Initially, they thought that the organism was a member of the genus Leishmania; therefore, they described it as “Leishmania gondii. Later they realized that they have discovered a new organism, which causes disease toxoplasmosis. Consequently, they named it Toxoplasma gondii. Next, he started researching on typhus, which used to take up an epidemical proportion in Tunisia every winter. It was also rampant in jails.

Nicolle discovered that blood serum from patients who had survived and were recovering from typhus could be used as a temporary vaccine against typhus. Doctors and nurses who were vaccinated in this way were immune from the disease, but not for long. Between 1910 and 1914, Nicolle and his colleagues in Tunis proved that typhus is carried in louse excrement. Anyone carrying infected lice who scratches themselves picks up louse excrement on their fingers and fingernails. The disease enters their bodies if they rub their eyes, which are particularly susceptible to the infectious agent or scratch their skin.

Subsequently, Nicolle published two reports at the French Academy of Sciences. They were ‘Reproduction expérimentale du typhus exanthématique chez le singe’ and ‘Transmission expérimentale du typhus exanthématique par le pou du corps’. The later was written in collaboration with Charles Comte and E. Conseil. Next, Nicole along with E. Conseil undertook further research into protection against typhus. In 1910, he developed convalescent serum injections as protection against the disease. From 1911 onwards, Nicolle began working on recurring fevers. He not only introduced preventive vaccination for Malta fever but also contributed immensely towards the understanding of the disease. In addition, he also discovered how tick fever was transmitted and worked on scarlet fever, rinderpest, measles, influenza, tuberculosis, etc.

Nicolle’s discovery immediately ended typhus epidemics in the western world. Simply put, no lice means no typhus. Keeping people free of lice meant keeping them free of the disease. The enormous death toll in World War 1 would probably have been far worse but for Nicolle’s discovery.

In 1918, towards the end of World War I there was an outbreak of influenza over a large area, which threatened to take the form of an epidemic. Nicolle worked on it and with Charles Lebailly and showed that it was caused by a filtering virus, which he named ‘infra-microbe’. Later in 1919, he started further research on typhus on rats and guinea pigs. Soon he distinguished between lice-borne epidemic typhus and murine typhus, which is borne by rat-flea. Subsequently, he also developed the concept of ‘non-appearing’ infection. Nicolle continued working until the end. In 1923, he co-founded and chaired the International League against Trachoma. He also traveled a lot visiting Greece in 1924 and Mexico in 1931.

While researching typhus, Nicolle found that some guinea pigs could carry the disease in their blood but never show any symptoms. Lice from these guinea pigs could infect others causing them to become ill with typhus. Nicolle then discovered other infectious diseases could be carried in the same way, the disease spread by apparently healthy individuals. This was a vital development in untangling the epidemiology of infectious diseases. Nicolle regarded it as his most important scientific discovery.

Charles Nicole was not only a great bacteriologist; he was also a great writer. Apart from several works on biological and medical philosophy he had also published several novels such as : “Le Pâtissier de Bellone” (1913), “Les Feuilles de la Sagittaire” (1920), “La Narquoise” (1922), “Les Menus Plaisirs de l’Ennui” (1924), “Marmouse et ses hôtes” (1927), “Les Deux Larrons” (1929), “Les Contes de Marmouse et ses hôtes” (1930).

Awards and Honor

Charles Nicolle was the sole recipient of the 1928 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine “for his work on typhus.” A year before that he had also received Osiris prize for the same work.

In 1929, Nicolle was named a non-resident member of the French Academy of Medicine.

Death and Legacy

Charles Nicolle died on 28 February 1936 in Tunis, the capital city of Tunisia. He was the Director of the Pasteur Institute at Tunis at the time of his death. He was buried in a tomb at the Pasteur Institute in Tunis.

Nicolle extended his work on typhus to distinguish between the classical louse-borne form of the disease and murine typhus, which is conveyed to humans by the rat flea. He also made valuable contributions to the knowledge of rinderpest, brucellosis, measles, diphtheria, and tuberculosis.

Charles Nicolle is best remembered for his work on typhus. During his stay at Tunis, he observed that the disease razed the countryside in the winter and subsided in summer. He also observed that those who transmitted typhus even at the door of the hospital ceased to be contagious as soon as they are admitted. He noticed that on being admitted to the hospital the patients were first made to have a shave and then a bath. Their clothes were confiscated as well. He suspected that it was either a patient’s clothes or their skin, which carried the vector of the disease. He further surmised that the culprit was none other than the body louse. He proved it in 1909 after a series of experiments involving chimpanzees. He further showed that the transmission actually occurred through the excrement of the louse, which contains a large number of microbes. The person becomes infected when he/she unknowingly rub it into the skin or eye.

Nicolle also tried to make a simple vaccine for typhus. He crushed the lice and mixed it with blood serum, collected from recovered patients. He successfully tried it first on himself and then on a few children. However, the practical vaccine was later invented by Polish biologist Rudolf Stefan Weigl.

Information Source: