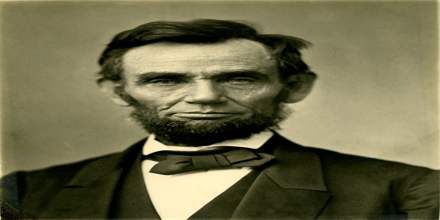

Abraham Lincoln – 16th President of the United States (1809-1865)

Name: Abraham Lincoln

Date of birth: February 12, 1809

Place of birth: Hodgenville, Kentucky, U.S.

Date of death: April 15, 1865 (aged 56)

Place of death: Petersen House, Washington, D.C., U.S.

Cause of death: Assassination

Nationality: American

Height: 6 ft 4 in (193 cm)

Spouse(s): Mary Todd (m. 1842)

Children: Robert, Edward, Willie, and Tad

Profession: Lawyer, Politician

Political party: Whig (1834–1854), Republican (1854–1865)

Early Life

Abraham Lincoln was born on Feb 12, 1809, in Hardin Country, Kentucky, U.S. He was an American politician and lawyer who served as the 16th President of the United States from March 1861 until his assassination in April 1865. Lincoln led the United States through its Civil War—its bloodiest war and perhaps its greatest moral, constitutional, and political crisis. In doing so, he preserved the Union, abolished slavery, strengthened the federal government, and modernized the economy.

Abraham Lincoln is regarded as one of America’s greatest heroes due to both his incredible impact on the nation and his unique appeal. His is a remarkable story of the rise from humble beginnings to achieve the highest office in the land; then, a sudden and tragic death at a time when his country needed him most to complete the great task remaining before the nation.

Lincoln’s distinctively human and humane personality and historical role as savior of the Union and emancipator of the slaves creates a legacy that endures. His eloquence of democracy and his insistence that the Union was worth saving embody the ideals of self-government that all nations strive to achieve.

Elected to the United States House of Representatives in 1846, Lincoln promoted rapid modernization of the economy through banks, tariffs, and railroads. Because he had originally agreed not to run for a second term in Congress, and because his opposition to the Mexican–American War was unpopular among Illinois voters, Lincoln returned to Springfield and resumed his successful law practice. Reentering politics in 1854, he became a leader in building the new Republican Party, which had a statewide majority in Illinois. In 1858, while taking part in a series of highly publicized debates with his opponent and rival, Democrat Stephen A. Douglas, Lincoln spoke out against the expansion of slavery, but lost the U.S. Senate race to Douglas.

Lincoln initially concentrated on the military and political dimensions of the war. His primary goal was to reunite the nation. He suspended habeas corpus, leading to the controversial ex parte Merryman decision, and he averted potential British intervention in the war by defusing the Trent Affair in late 1861. Lincoln closely supervised the war effort, especially the selection of top generals, including his most successful general, Ulysses S. Grant. He also made major decisions on Union war strategy, including a naval blockade that shut down the South’s normal trade, moves to take control of Kentucky and Tennessee, and using gunboats to gain control of the southern river system.

An exceptionally astute politician deeply involved with power issues in each state, Lincoln reached out to the War Democrats and managed his own re-election campaign in the 1864 presidential election. Anticipating the war’s conclusion, Lincoln pushed a moderate view of Reconstruction, seeking to reunite the nation speedily through a policy of generous reconciliation in the face of lingering and bitter divisiveness. On April 14, 1865, five days after the surrender of Confederate commanding general Robert E. Lee, Lincoln was assassinated by John Wilkes Booth, a Confederate sympathizer.

Lincoln has been consistently ranked both by scholars and the public as among the three greatest U.S. presidents.

Educational and Childhood Career

When young Abraham was 9 years old, his mother died on October 5, 1818, of tremetol (milk sickness) at age 34. The event was devastating on him and young Abraham grew more alienated from his father and quietly resented the hard work placed on him at an early age. Just over a year after Nancy’s death, in December 1819, Thomas married Sarah Bush Johnston, a Kentucky widow with three children of her own. She was a strong and affectionate woman with whom Abraham quickly bonded. Though both his parents were most likely illiterate, Sarah encouraged Abraham to read.

As a youth, Lincoln disliked the hard labor associated with frontier life. Some of his neighbors and family members thought for a time that he was lazy for all his “reading, scribbling, writing, ciphering, writing Poetry, etc.”, and must have done it to avoid manual labor. His stepmother also acknowledged he did not enjoy “physical labor”, but loved to read.

Lincoln was largely self-educated. His formal schooling from several itinerant teachers was intermittent, the aggregate of which may have amounted to less than a year; however, he was an avid reader and retained a lifelong interest in learning.

Family, neighbors, and schoolmates of Lincoln’s youth recalled that he read and reread the King James Bible, Aesop’s Fables, Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress, Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe, Weems’s The Life of Washington, and Franklin’s Autobiography, among others.

He also complied with the customary obligation of a son giving his father all earnings from work done outside the home until the age of twenty-one. Abraham became adept at using an axe. Tall for his age, Lincoln was also strong and athletic. He attained a reputation for brawn and audacity after a very competitive wrestling match with the renowned leader of a group of ruffians known as “the Clary’s Grove boys”.

In early March 1830, fearing a milk sickness outbreak along the Ohio River, the Lincoln family moved west to Illinois, a non-slaveholding state. They settled on a site in Macon County, Illinois, 10 miles (16 km) west of Decatur. Historians disagree on who initiated the move. After the family relocated to Illinois, Abraham became increasingly distant from his father, in part because of his father’s lack of education, and occasionally lent him money. In 1831, as Thomas and other members of the family prepared to move to a new homestead in Coles County, Illinois, Abraham was old enough to make his own decisions and struck out on his own. Traveling down the Sangamon River, he ended up in the village of New Salem in Sangamon County. Later that spring, Denton Offutt, a New Salem merchant, hired Lincoln and some friends to take goods by flatboat from New Salem to New Orleans via the Sangamon, Illinois, and Mississippi rivers. After arriving in New Orleans—and witnessing slavery firsthand—Lincoln returned to New Salem, where he remained for the next six years.

Lawyer Career

Lincoln returned to practicing law in Springfield, handling “every kind of business that could come before a prairie lawyer”. Twice a year for 16 years, 10 weeks at a time, he appeared in county seats in the midstate region when the county courts were in session. Lincoln handled many transportation cases in the midst of the nation’s western expansion, particularly the conflicts arising from the operation of river barges under the many new railroad bridges.

In 1851, he represented the Alton & Sangamon Railroad in a dispute with one of its shareholders, James A. Barret, who had refused to pay the balance on his pledge to buy shares in the railroad on the grounds that the company had changed its original train route.

Lincoln successfully argued that the railroad company was not bound by its original charter extant at the time of Barret’s pledge; the charter was amended in the public interest to provide a newer, superior, and less expensive route, and the corporation retained the right to demand Barret’s payment. The decision by the Illinois Supreme Court has been cited by numerous other courts in the nation. Lincoln appeared before the Illinois Supreme Court in 175 cases, in 51 as sole counsel, of which 31 were decided in his favor. From 1853 to 1860, another of Lincoln’s largest clients was the Illinois Central Railroad. Lincoln’s reputation with clients gave rise to his nickname “Honest Abe.”

Lincoln’s most notable criminal trial occurred in 1858 when he defended William “Duff” Armstrong, who was on trial for the murder of James Preston Metzker. The case is famous for Lincoln’s use of a fact established by judicial notice in order to challenge the credibility of an eyewitness. After an opposing witness testified seeing the crime in the moonlight, Lincoln produced a Farmers’ Almanac showing the moon was at a low angle, drastically reducing visibility. Based on this evidence, Armstrong was acquitted.

Political Career

In 1846, Lincoln was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, where he served one two-year term. He was the only Whig in the Illinois delegation, but he showed his party loyalty by participating in almost all votes and making speeches that echoed the party line.

On foreign and military policy, Lincoln spoke out against the Mexican–American War, which he attributed to President Polk’s desire for “military glory—that attractive rainbow, that rises in showers of blood”. Lincoln also supported the Wilmot Proviso, which, if it had been adopted, would have banned slavery in any U.S. territory won from Mexico.

By the 1850s, slavery was still legal in the southern United States, but had been outlawed in all the northern states since 1803, including Illinois, whose original 1818 Constitution forbade slavery. Lincoln disapproved of slavery, but he only demanded the end to the spread of slavery to new territory in the west. He returned to politics to oppose the pro-slavery Kansas–Nebraska Act (1854); this law repealed the slavery-restricting Missouri Compromise (1820). Senior Senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois had incorporated popular sovereignty into the Act. Douglas’ provision, which Lincoln opposed, specified settlers had the right to determine locally whether to allow slavery in new U.S. territory, rather than have such a decision restricted by the national Congress.

On October 16, 1854, in his “Peoria Speech”, Lincoln declared his opposition to slavery, which he repeated en route to the presidency. Speaking in his Kentucky accent, with a very powerful voice, he said the Kansas Act had a “declared indifference, but as I must think, a covert real zeal for the spread of slavery. I cannot but hate it. I hate it because of the monstrous injustice of slavery itself. I hate it because it deprives our republican example of its just influence in the world …”

In late 1854, Lincoln ran as a Whig for the U.S. Senate. At that time, senators were elected by the state legislature. After leading in the first six rounds of voting, but unable to obtain a majority, Lincoln instructed his backers to vote for Lyman Trumbull. Trumbull was an antislavery Democrat, and had received few votes in the earlier ballots; his supporters, also antislavery Democrats, had vowed not to support any Whig. Lincoln’s decision to withdraw enabled his Whig supporters and Trumbull’s antislavery Democrats to combine and defeat the mainstream Democratic candidate, Joel Aldrich Matteson.

Drawing on the antislavery portion of the Whig Party, and combining Free Soil, Liberty, and antislavery Democratic Party members, the new Republican Party formed as a northern party dedicated to antislavery. Lincoln was one of those instrumental in forging the shape of the new party; at the 1856 Republican National Convention, he placed second in the contest to become its candidate for vice president.

After the state Republican party convention nominated him for the U.S. Senate in 1858, Lincoln delivered his House Divided Speech, “A house divided against itself cannot stand. I believe this government cannot endure permanently half slave and half free. I do not expect the Union to be dissolved—I do not expect the house to fall—but I do expect it will cease to be divided. It will become all one thing, or all the other.” The speech created an evocative image of the danger of disunion caused by the slavery debate, and rallied Republicans across the North. The stage was then set for the campaign for statewide election of the Illinois legislature which would, in turn, select Lincoln or Douglas as its U.S. senator.

The Senate campaign featured the seven Lincoln–Douglas debates of 1858, the most famous political debates in American history.

On February 27, 1860, New York party leaders invited Lincoln to give a speech at Cooper Union to a group of powerful Republicans.

On May 9–10, 1860, the Illinois Republican State Convention was held in Decatur. Lincoln’s followers organized a campaign team led by David Davis, Norman Judd, Leonard Swett, and Jesse DuBois, and Lincoln received his first endorsement to run for the presidency. Exploiting the embellished legend of his frontier days with his father (clearing the land and splitting fence rails with an ax), Lincoln’s supporters adopted the label of “The Rail Candidate”. In 1860 Lincoln described himself : “I am in height, six feet, four inches, nearly; lean in flesh, weighing, on an average, one hundred and eighty pounds; dark complexion, with coarse black hair, and gray eyes.”

Abraham Lincoln responded to the crisis wielding powers as no other president before him. He distributed $2 million from the Treasury for war material without an appropriation from Congress; he called for 75,000 volunteers into military service without a declaration of war; and he suspended the writ of habeas corpus, arresting and imprisoning suspected Confederate sympathizers without a warrant. Crushing the rebellion would be difficult under any circumstances, but the Civil War, with its preceding decades of white-hot partisan politics, was especially onerous. From all directions, Lincoln faced disparagement and defiance. He was often at odds with his generals, his Cabinet, his party and a majority of the American people.

The Union Army’s first year and a half of battlefield defeats made it especially difficult to keep morale up and support strong for a reunification the nation. With the hopeful, but by no means conclusive Union victory at Antietam on September 22, 1862, Lincoln felt confident enough to reshape the cause of the war from saving the union to abolishing slavery. He issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, which stated that all individuals who were held as slaves in rebellious states “henceforward shall be free.” The action was more symbolic than effective because the North didn’t control any states in rebellion and the proclamation didn’t apply to Border States, Tennessee or some Louisiana parishes.

Gradually, the war effort improved for the North, though more by attrition than by brilliant military victories. But by 1864, the Confederate armies had eluded major defeat and Lincoln was convinced he’d be a one-term president. His nemesis, George B. McClellan, the former commander of the Army of the Potomac, challenged him for the presidency, but the contest wasn’t even close. Lincoln received 55 percent of the popular vote and 212 of 243 Electoral votes. On April 9, 1865, General Robert E. Lee, commander of the Army of Virginia, surrendered his forces to Union General Ulysses S. Grant and the war for all intents and purposes was over.

Presidency Career

On November 6, 1860, Lincoln was elected the 16th president of the United States, beating Democrat Stephen A. Douglas, John C. Breckinridge of the Southern Democrats, and John Bell of the new Constitutional Union Party. He was the first president from the Republican Party. His victory was entirely due to the strength of his support in the North and West; no ballots were cast for him in 10 of the 15 Southern slave states, and he won only two of 996 counties in all the Southern states.

Although Lincoln won only a plurality of the popular vote, his victory in the electoral college was decisive: Lincoln had 180 and his opponents added together had only 123. There were fusion tickets in which all of Lincoln’s opponents combined to support the same slate of Electors in New York, New Jersey, and Rhode Island, but even if the anti-Lincoln vote had been combined in every state, Lincoln still would have won a majority in the Electoral College.

The Crittenden Compromise would have extended the Missouri Compromise line of 1820, dividing the territories into slave and free, contrary to the Republican Party’s free-soil platform. Lincoln rejected the idea, saying, “I will suffer death before I consent … to any concession or compromise which looks like buying the privilege to take possession of this government to which we have a constitutional right.”

On August 6, 1861, Lincoln signed the Confiscation Act that authorized judiciary proceedings to confiscate and free slaves who were used to support the Confederate war effort. In practice, the law had little effect, but it did signal political support for abolishing slavery in the Confederacy.

The commander of Fort Sumter, South Carolina, Major Robert Anderson, sent a request for provisions to Washington, and the execution of Lincoln’s order to meet that request was seen by the secessionists as an act of war. On April 12, 1861, Confederate forces fired on Union troops at Fort Sumter, forcing them to surrender, and began the war. Historian Allan Nevins argued that the newly inaugurated Lincoln made three miscalculations: underestimating the gravity of the crisis, exaggerating the strength of Unionist sentiment in the South, and not realizing the Southern Unionists were insisting there be no invasion.

On April 15, Lincoln called on all the states to send detachments totaling 75,000 troops to recapture forts, protect Washington, and “preserve the Union”, which, in his view, still existed intact despite the actions of the seceding states. This call forced the states to choose sides. Virginia declared its secession and was rewarded with the Confederate capital, despite the exposed position of Richmond so close to Union lines. North Carolina, Tennessee, and Arkansas also voted for secession over the next two months. Secession sentiment was strong in Missouri and Maryland, but did not prevail; Kentucky tried to be neutral. The Confederate attack on Fort Sumter rallied Americans north of the Mason-Dixon Line to the defense of the American nation.

Gradually, the war effort improved for the North, though more by attrition than by brilliant military victories. Lincoln was a master politician, bringing together—and holding together—all the main factions of the Republican Party, and bringing in War Democrats such as Edwin M. Stanton and Andrew Johnson as well. Lincoln spent many hours a week talking to politicians from across the land and using his patronage powers—greatly expanded over peacetime—to hold the factions of his party together, build support for his own policies, and fend off efforts by Radicals to drop him from the 1864 ticket. But by 1864, the Confederate armies had eluded major defeat and Lincoln was convinced he’d be a one-term president. His nemesis, George B. McClellan, the former commander of the Army of the Potomac, challenged him for the presidency, but the contest wasn’t even close. Lincoln received 55 percent of the popular vote and 212 of 243 Electoral votes. On April 9, 1865, General Robert E. Lee, commander of the Army of Virginia, surrendered his forces to Union General Ulysses S. Grant and the war for all intents and purposes was over.

Personal Life

Abraham Lincoln was born February 12, 1809, the second child of Thomas and Nancy Hanks Lincoln, in a one-room log cabin on the Sinking Spring Farm in Hardin County, Kentucky (now LaRue County). Born in Hodgenville, Kentucky, Lincoln grew up on the western frontier in Kentucky and Indiana.

He was a descendant of Samuel Lincoln, who migrated from Norfolk, England to Hingham, Massachusetts, in 1638. Samuel’s grandson and great-grandson began the family’s western migration, which passed through New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Virginia. Lincoln’s paternal grandfather and namesake, Captain Abraham Lincoln, moved the family from Virginia to Jefferson County, Kentucky in the 1780s. Captain Lincoln was killed in an Indian raid in 1786. His children, including eight-year-old Thomas, the future president’s father, witnessed the attack.

Lincoln’s mother, Nancy, is widely assumed to have been the daughter of Lucy Hanks, although no record of Nancy Hanks’ birth has ever been found.

(Abraham Lincoln with his family)

(Abraham Lincoln with his family)

Thomas Lincoln and Nancy Hanks were married on June 12, 1806, in Washington County, and moved to Elizabethtown, Kentucky, following their marriage. They became the parents of three children: Sarah, born on February 10, 1807; Abraham, on February 12, 1809; and another son, Thomas, who died in infancy. Thomas Lincoln bought or leased several farms in Kentucky, including the Sinking Spring farm, where Abraham was born; however, a land title dispute soon forced the Lincolns to move. In 1811 the family moved eight miles (13 km) north, to Knob Creek Farm, where Thomas acquired title to 230 acres (93 ha) of land.

On October 5, 1818, Nancy Lincoln died of milk sickness, leaving eleven-year-old Sarah in charge of a household that included her father, nine-year-old Abraham, and Dennis Hanks, Nancy’s nineteen-year-old orphaned cousin. On December 2, 1819, Lincoln’s father married Sarah “Sally” Bush Johnston, a widow from Elizabethtown, Kentucky, with three children of her own. Abraham became very close to his stepmother, whom he referred to as “Mother”. Those who knew Lincoln as a teenager later recalled him being very distraught over his sister Sarah’s death on January 20, 1828, while giving birth to a stillborn son.

In early March 1830, fearing a milk sickness outbreak along the Ohio River, the Lincoln family moved west to Illinois, a non-slaveholding state. They settled on a site in Macon County, Illinois, 10 miles (16 km) west of Decatur.

Lincoln’s first romantic interest was Ann Rutledge, whom he met when he first moved to New Salem; by 1835, they were in a relationship but not formally engaged. She died at the age of 22 on August 25, 1835, most likely of typhoid fever. In the early 1830s, he met Mary Owens from Kentucky when she was visiting her sister.

Late in 1836, Lincoln agreed to a match with Mary if she returned to New Salem. Mary did return in November 1836, and Lincoln courted her for a time; however, they both had second thoughts about their relationship. On August 16, 1837, Lincoln wrote Mary a letter suggesting he would not blame her if she ended the relationship. She never replied and the courtship ended.

In 1840, Lincoln became engaged to Mary Todd, who was from a wealthy slave-holding family in Lexington, Kentucky. They met in Springfield, Illinois, in December 1839 and were engaged the following December. A wedding set for January 1, 1841, was canceled when the two broke off their engagement at Lincoln’s initiative. They later met again at a party and married on November 4, 1842, in the Springfield mansion of Mary’s married sister.

He was an affectionate, though often absent, husband and father of four children. Robert Todd Lincoln was born in 1843 and Edward Baker Lincoln (Eddie) in 1846. Edward died on February 1, 1850, in Springfield, probably of tuberculosis. “Willie” Lincoln was born on December 21, 1850, and died of a fever on February 20, 1862. The Lincolns’ fourth son, Thomas “Tad” Lincoln, was born on April 4, 1853, and died of heart failure at the age of 18 on July 16, 1871. Robert was the only child to live to adulthood and have children. The Lincolns’ last descendant, great-grandson Robert Todd Lincoln Beckwith, died in 1985. Lincoln “was remarkably fond of children”, and the Lincolns were not considered to be strict with their own.

Death

Reconstruction began during the war as early as 1863 in areas firmly under Union military control. Abraham Lincoln favored a policy of quick reunification with a minimum of retribution. But he was confronted by a radical group of Republicans in the Senate and House that wanted complete allegiance and repentance from former Confederates. Before a political battle had a chance to firmly develop, Lincoln was assassinated on April 14, 1865, by well-known actor and Confederate sympathizer John Wilkes Booth at Ford’s Theater in Washington, D.C. Lincoln was taken from the theater to a Petersen House across the street and laid in a coma for nine hours before dying the next morning. His body lay in state at the Capitol before a funeral train took him back to his final resting place in Springfield, Illinois.

Honours and Memorials

(Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C.)

(Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C.)

Lincoln’s portrait appears on two denominations of United States currency, the penny and the $5 bill. His likeness also appears on many postage stamps and he has been memorialized in many town, city, and county names, including the capital of Nebraska.

The most famous and most visited memorials are Lincoln’s sculpture on Mount Rushmore; Lincoln Memorial, Ford’s Theatre, and Petersen House (where he died) in Washington, D.C.; and the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum in Springfield, Illinois, not far from Lincoln’s home, as well as his tomb.

There was also the Great Moments with Mr. Lincoln exhibit in Disneyland, and the Hall of Presidents at Walt Disney World, which had to do with Walt Disney admiring Lincoln ever since he was a little boy.

Barry Schwartz, a sociologist who has examined America’s cultural memory, argues that in the 1930s and 1940s, the memory of Abraham Lincoln was practically sacred and provided the nation with “a moral symbol inspiring and guiding American life”. During the Great Depression, he argues, Lincoln served “as a means for seeing the world’s disappointments, for making its sufferings not so much explicable as meaningful”. Franklin D. Roosevelt, preparing America for war, used the words of the Civil War president to clarify the threat posed by Germany and Japan. Americans asked, “What would Lincoln do?” However, Schwartz also finds that since World War II, Lincoln’s symbolic power has lost relevance, and this “fading hero is symptomatic of fading confidence in national greatness”. He suggested that postmodernism and multiculturalism have diluted greatness as a concept.

The United States Navy Nimitz-class aircraft carrier USS Abraham Lincoln (CVN-72) is named after Lincoln, the second Navy ship to bear his name.

(Lincoln’s image is carved into the stone of Mount Rushmore)

(Lincoln’s image is carved into the stone of Mount Rushmore)

In surveys of U.S. scholars ranking presidents conducted since the 1940s, Lincoln is consistently ranked in the top three, often as number one. A 2004 study found that scholars in the fields of history and politics ranked Lincoln number one, while legal scholars placed him second after Washington. In presidential ranking polls conducted in the United States since 1948, Lincoln has been rated at the very top in the majority of polls: Schlesinger 1948, Schlesinger 1962, 1982 Murray Blessing Survey, Chicago Tribune 1982 poll, Schlesinger 1996, CSPAN 1996, Ridings-McIver 1996, Time 2008, and CSPAN 2009. Generally, the top three presidents are rated as 1. Lincoln; 2. George Washington; and 3. Franklin D. Roosevelt, although Lincoln and Washington, and Washington and Roosevelt, are occasionally reversed.