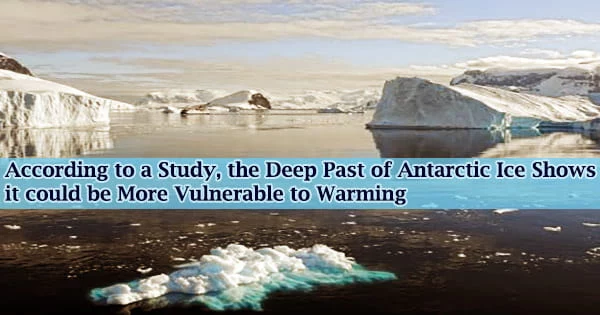

Understanding how the West Antarctic Ice Sheet reacted to a warmer climate millions of years ago could help scientists forecast how it will respond in the future.

The new research, headed by Imperial College London scientists, looked at the state of Antarctic ice sheets during the Early Miocene, which lasted roughly 18-16 million years and had both warm and cold times. Sea level surged up to 60 meters during warmer periods, the equivalent of melting all of the ice on the Antarctic continent.

However, it was unclear how much the bigger East Antarctic Ice Sheet (EAIS) and the smaller West Antarctic Ice Sheet (WAIS) contributed to the past sea-level increase. Imperial scientists working as part of the International Ocean Discovery Program have now demonstrated that the WAIS was larger than previously assumed during colder Miocene times, according to research published today in Nature.

This suggests it played a much larger role in millions of years ago sea-level rise episodes than previously imagined. This knowledge will aid researchers in predicting the WAIS’s future as the planet heats.

Before the late Miocene, around 10 million years ago, it was considered that the WAIS was relatively modest and that sea-level rise was largely caused by melting of the larger East Antarctic Ice Sheet (EAIS), which may have melted completely during the warmest times of the last 23 million years.

Despite the fact that geological records show massive sea-level rise occurrences, ice sheet models suggest that sections of the EAIS remained even during the Miocene’s warmest periods, circa 23-5 million years ago.

While Antarctica is losing mass at an accelerating rate today, projected sea-level rise by the end of this century is nowhere close to the levels that we know existed in the geological past when temperatures were one, two, or three degrees warmer. Hence the past is an important window to tell us what we are committing the planet to with certain amounts of warming.

Tina van de Flierdt

The Science and Solutions for a Changing Planet Doctoral Training Partnership is helping lead author Jim Marschalek of Imperial College’s Department of Earth Science and Engineering finish his Ph.D. He said:

“Our observations from the past help inform predictions of how the West Antarctic Ice Sheet, which is considered particularly vulnerable to rapid ice mass loss today, will respond under various future warming scenarios.”

The researchers looked for strata that matched to the coldest and warmest eras in sediments in the Ross Sea, Antarctica. They discovered material deposited by a WAIS far out at sea, demonstrating that it grew enormous during the coldest eras.

This was feasible because, in the past, more of the land surface beneath the WAIS was above sea level, allowing more ice to accumulate on this area of the continent than it does now. Despite these geographic shifts, this study demonstrates how the WAIS could significantly boost sea levels in the future as our world warms.

The WAIS is now widely regarded as being extremely vulnerable to the ocean and atmospheric warming. This new study backs up that theory, demonstrating that it grew and shrank dramatically during the Miocene.

The current rate of human-caused climate warming is extremely rapid. Scientists may be more sure that the models are capturing the behavior of the WAIS in the past now that geological data corresponds with the models, allowing them to forecast how Antarctica would respond to changes in the short term as well as over hundreds to thousands of years.

The findings also show that if major action is not made immediately to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, the effects of climate change on Antarctica’s ice sheets would persist.

Co-author Professor Tina van de Flierdt, from the Department of Earth Science and Engineering at Imperial, said: “While Antarctica is losing mass at an accelerating rate today, projected sea-level rise by the end of this century is nowhere close to the levels that we know existed in the geological past when temperatures were one, two, or three degrees warmer. Hence the past is an important window to tell us what we are committing the planet to with certain amounts of warming.”

“The good news is that the large ice sheets are relatively sluggish to respond to environmental change, so we might still be able to avoid major ice loss in many areas. The bad news is that the low-lying areas of the ice sheet have a ‘tipping point’, and we do not yet fully understand where this point of no return lies.”

The goal is to keep future warming below two degrees Celsius, ideally 1.5 degrees Celsius, which will necessitate a 50% reduction in emissions by 2030.

The research also revealed that the huge WAIS was extremely erosive, implying that more land area was lost to the sea, permanently increasing the West Antarctic Ice Sheet’s susceptibility to shifting ocean conditions.

Future research is needed to better understand the low-lying and vulnerable portions of both the smaller West Antarctic ice sheet and the larger East Antarctic ice sheet, according to the scientists.