The quantity of fungi from the potentially pathogenic Candida genus can be estimated from the bacteria found in the intestine. Surprisingly, lactic acid bacteria, which are recognized for guarding against fungal infections, are among them.

Understanding the human gut microbiota now has another element thanks to the work of scientists at the Leibniz Institute for Natural Product Research and Infection Biology (Leibniz-HKI) and its international collaborators from Denmark and Hungary.

The human gut microbiome is an incredibly intricate ecosystem where various microbes regulate one another. An imbalance brought on by drugs or other environmental factors, however, can cause a species to spread and infect people.

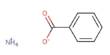

Fungi of the Candida genus, for example, are present in the intestines of many healthy people. They are usually harmless, but can also cause dangerous systemic infections.

Studying these interactions in the intestine is difficult. Only a small portion of the several hundred different species of bacteria and fungi can be successfully grown in a lab, and many of them are even unknown. Researchers at the Leibniz-HKI are therefore trying to shed more light on the intestine using metagenome studies.

Researchers investigated stool samples from 75 cancer patients for the study, which is now published in Nature Communications, and discovered that specific bacterial species usually show up in increased numbers when the proportion of fungi from the Candida genus is also high.

“With these data, we developed a computer model that was able to predict the amount of Candida in another group of patients with an accuracy of about 80% based on bacterial species and amounts alone,” explains Bastian Seelbinder, lead author of the study. These bacteria included mainly oxygen-tolerant species.

We found an increased number of bacterial species that produce lactic acid, including Lactobacillus species. I could hardly believe it at first, so I checked several times, always with the same result.

Bastian Seelbinder

A surprising find

Seelbinder conducts research in Gianni Panagiotou’s Microbiome Dynamics department at Leibniz-HKI, which focuses intensively on the gut microbiome. The ability to accurately anticipate the amount of fungi present based on the bacterial species present as well as which bacteria connected with high amounts of fungi shocked the researchers.

“We found an increased number of bacterial species that produce lactic acid, including Lactobacillus species,” Seelbinder explains. It’s a finding he had not expected. “I could hardly believe it at first, so I checked several times, always with the same result.”

The reason for his surprise: Several studies have attested to the protective effect of lactic acid bacteria against fungal infections. One of them was published last year by Panagiotou’s group, also in the journal Nature Communications.

“The result shows once again how complex the human gut microbiome is and how difficult it is to decipher the interactions of different microorganisms,” Panagiotou says.

The researchers’ hunch: Lactic acid bacteria, particularly of the genus Lactobacillus, favor Candida proliferation but at the same time make the fungus less virulent. This might be as a result of Candida species’ ability to change their metabolism so they can use the lactate made by lactic acid bacteria. The researchers found that this gives them a competitive edge over other fungi like Saccharomyces cerevisiae in additional studies.

The metabolic switch also appears to prevent Candida from developing the potentially harmful fungal hyphae that could infiltrate the intestinal mucosa, keeping it in its typically benign spherical yeast form.

Strategies for high-risk patients

“There is also a suggestion that certain groups of Lactobacillus species might have different effects,” Seelbinder says. To investigate this, the next step will be to perform more detailed genomic analyses of the bacteria.

“For the current study, we examined stool samples from cancer patients who are particularly at risk for fungal infections,” Panagiotou explains. “For further studies, samples from healthy subjects could be included to develop long-term strategies for at-risk patients based on their microbiome.”

For their studies, the Leibniz-HKI researchers cooperated with teams from the Korányi National Institute of Pulmonology in Hungary, the Technical University of Denmark and Jena University Hospital, among others.