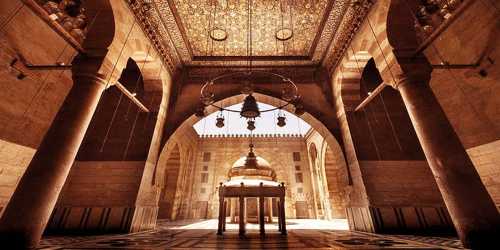

Mosque-Madrassa of Sultan Barquq or Mosque-Madrassa-Khanqah of Az-Zaher Barquq (Arabic: مسجد ومدرسة وخانقاه الظاهر برقوق) stands in the center of one of the largest architectural heritage complexes in the world. It is a religious complex in Egypt’s Islamic Cairo, Cairo’s historic medieval district. Its construction, which began in 786 AH / 1384 AD, was ordered by King Zahir Abu Sa’id Barquq. It was the first architectural facility constructed during the Mamluk Sultanate era of the Circassian (Burji) dynasty. Part of the building was supervised by the architect Shihab al-Din Ahmad ibn Muhammad al Tuluni, who belonged to a family of court architects and surveyors. In the opening inscription on the facade and in the courtyard, the name of Jarkas al Khalili, the master of Barquq ‘s horse and the founder of the famous Khan al Khalili, appears. In addition, as part of Bayn al-Qasrayn Lane, the mosque is embedded in Egyptian society’s fabric and Egyptian citizens’ daily lives. One of its lesser-known goals in the 1970s was to provide housing for evicted families. Al-Nasir Muhammad Ibn Qalawun founded a charitable foundation for his madrasa here. The four Islamic legal schools were taught by the school itself and included a mosque and a Sufi khanqa. A domed sanctuary inside the structure fills in as the internment spot of Sultan Barquq’s dad and of a portion of his spouses and kids. Like most Mamluk establishments, Barquq’s strict complex served a few capacities one after another. The establishment deed expresses that the complex incorporates a Friday mosque, a madrasa that showed the four Sunni madhhabs for 125 understudies, and a khanqah (a religious community type foundation for Sufis) for 60 Sufis. To accentuate the coherence he expected he picked a site close to the early Qalawunid landmarks on the prestigious al-Mu’izz Street. This culminated in a continuous wall of neighboring facades with recesses of windows, portals, crestings, domes, minarets, and tiraz bands, all executed in various styles vying for visual supremacy and attesting to the powerful role of architecture in the political arena of Mamluk. On the stage provided by the dismantled Fatimid palaces, each facade reflects an episode in history.

Interior with a sahn and four iwans

An architectural wonder is the building (mosque), with its many beautiful architectural and decorative features. It consists of an open court, four iwans, the largest of which is the one for prayer on the side of the line. It includes a marble mihrab, a wooden pulpit, a Qur’an stand, and a platform for prayer (dikka). An ornate and rare calligraphic design is used in the Qur’anic inscription, where the top lines of letters tie together into flower-like knots. The mirrors of the madrassa and the mausoleum refer to the two circular windows visible along the outer wall. The portal of the entrance rises to an ornamental stone vault with carved muqarnas. Below this is a large inlaid marble column, similar to an instance found in the vestibule of the Sultan Hassan madrassa and probably brought from Syria. The bronze doors of the entrance are finely carved with 18-pointed and 12-pointed star geometric designs, and have another inscription. In exhibiting a shaft with stone carving, the octagonal minaret departs from most minarets from this time, which replaces the inlaid stonework typical of the 14th c. in the 15th c. (e.g., Sarghatmish) minarets. The royal rank (blazon) is applied to simple artifacts and materials, probably because building materials are rare and precious, such as window stucco grilles and rough wood. The facility was also fitted with many branch schools, Sufi wings, student quarters, a kitchen, and a washroom. The façade of the building is surmounted by a minaret and a dome that was restored by the 1310 AH / 1892 AD Assembly for the Protection of Arab Antiquities. A basilica-style plan similar to that found in the madrassa of the complex of Qalawun has the main prayer hall, with columns supporting the roof. The richly painted and carved wooden ceiling, however, is revolutionary and is considered to be an outstanding feature of this monument, with patterns similar to those in contemporary Quranic lighting. Marble mosaics and paneling adorn both the floor and the qibla wall (the wall defining the way of prayer). The original dome was made out of lead-covered wood. Using tiles, the dome had to be restored in 1893. Attempts were made by the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston to conserve the minbar door from May 2013 until February 2014. The intricate woodwork that is characteristic of the Mamluk style was also aimed at learning. In fifteenth-century Egypt, the addition of a Sufi curriculum to a madrasa represents the introduction of Sufism into urban life.