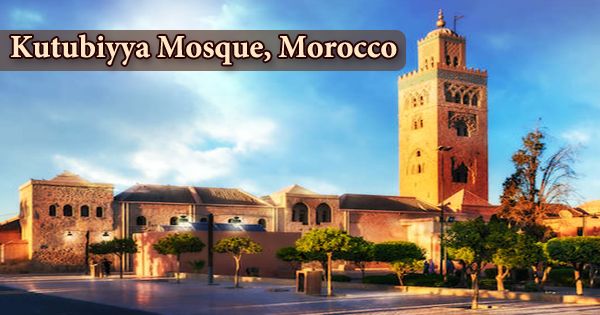

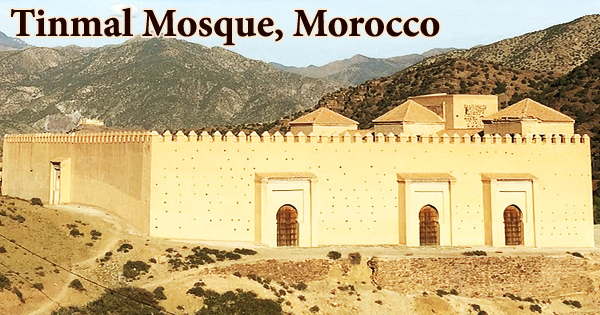

The Kutubiyya Mosque (Arabic: جامع الكتبية Arabic pronunciation: jaːmiʕu‿lkutubijːa(h)), also known as the Koutoubia Mosque, is the second of two nearly identical Kutubiyya mosques erected on the same location in the twelfth century by the Almohad king Abd-al-Mu’min. In Marrakesh, Morocco, it is the biggest mosque. Jami’ al-Kutubiyah, Kutubiya Mosque, Kutubiyyin Mosque, and Mosque of the Booksellers are all variations of the mosque’s name. It’s in Marrakesh’s southwest medina district, near the famed public square of Jemaa el-Fna, and is surrounded by huge gardens. While the dates for the construction of the two mosques are unknown, the sequence of events has been tentatively reconstructed using contemporaneous documents. Abd-al-Mu’min erected the first Kutubiyya mosque on the site of Ali bin Yusuf’s old palace in the southwest section of the medina after seizing Marrakech following the death of Almoravid leader Ali bin Yusuf in 1147/541 AH. After conquering Marrakesh from the Almoravids, the Almohad ruler Abd al-Mu’min built the mosque in 1147. Around 1158, Abd al-Mu’min completely restored the mosque, with Ya’qub al-Mansur potentially finishing the construction of the minaret around 1195. This is the current construction of the second mosque. It is regarded as a classic and significant example of Almohad and Moroccan mosque architecture in general. While the first mosque was constructed during the time of the Almoravid dynasty, the Almohad dynasty is claimed to have demolished it when they came to power because it did not correctly face Mecca. They started the present renovation of the mosque. As the Almohad kingdom extended north into Andalusia, the Koutoubia minaret served as a model for the Hassan II Mosque in Casablanca, as well as the Le Giralda in Seville, Spain. With its keystone arches and ornate masonry, the structure is a remarkable example of Moorish architecture. The 77-meter (253-foot) tall minaret tower is adorned with various geometric arch patterns and capped with a spire and metal orbs. The structure is rose-colored, like are all of Marrakech’s structures. The name koutoubia comes from the Arabic word for a bookstore; up to 100 booksellers used to trade at the mosque’s entrance and in the surrounding gardens back in the day. The mosque lies around 200 meters (660 feet) west of the city’s main market, the Jemaa El Fna souq, which has been around since the city’s founding. It is located on Avenue Mohammed V, directly across from Place de Foucauld. The mosque is still in use today, and non-Muslims are not permitted inside. However, the Tinmal Mosque, which was built following the same principles but is now dormant but maintained as a historic monument south of Marrakesh, may be visited.

The early history of the two Kutubuyyia mosques is mysterious, as it’s unclear why Abd-al-Mu’min built two almost similar mosques on the same location less than a decade apart. Several ideas have been offered to explain why Abd-al-Mu’min defied Muslim tradition by erecting only one Friday mosque in each city. According to some experts, the second mosque was erected to remedy the original mosque’s incorrect qibla orientation; nevertheless, the second qibla orientation is actually less accurate than the first. Others say that due to Marrakech’s expanding population, the old Kutubiyya mosque should be expanded to accommodate more attendees. According to a third theory, Abd-al-Mu’min wanted to commission as many public structures as possible in order to establish an outstanding personal legacy as a great builder. The Arabic word kutubiyyin (كُتُبيين), which means “booksellers,” is used in all of the titles and spellings of Kutubiyya Mosque, including Jami’ al-Kutubiyah, Kotoubia, Kutubiya, and Kutubiyyin. The respectable bookselling trade performed in the adjacent souk is reflected at the Koutoubia Mosque or Bookseller’s Mosque. At one point, there were up to 100 booksellers working in the streets near the mosque’s base. The second mosque was not built particularly to replace the first mosque, as the site was shared by two Kutubiyya mosques for at least thirty years. The original Kutubiyya mosque was only damaged after the building of the second Kutubiyya mosque. At the end of the 1990s, the mosque and its minaret were renovated. As part of an initiative to make state-run mosques more reliant on renewable green energy, the mosque was outfitted with solar panels, solar water heaters, and energy-efficient LED lighting in 2016. The first Kutubiyya mosque is shaped like a rectangle with an overall width of 80 meters east to west and a length of 60 meters north to south. To accommodate qibla orientation, the building’s longitudinal axis is turned twenty-six degrees counter-clockwise from the north-south meridian, however, a genuine orientation toward Mecca would need a counter-clockwise rotation of eighty-nine degrees in plan. The present mosque is approximately 90 meters broad, 57 meters long on the west side, and 66 meters long on the east side. Aside from the minaret, the mosque is mostly made of brick, while sections of the exterior walls are made of sandstone masonry. The first mosque was built with the same materials and procedures as the second. The courtyard was on the north side of the mosque, next to the bigger prayer hall on the south side. The prayer hall was designed in the T-shape seen in Abd-al-other Mu’min’s mosques, such as the mosque at Taza, the mosque at Tinmal, and the second Kutubiyya. The mosque has eight entrances, four on the west and four on the east sides. The entire length of the longitudinal naves was roughly 36 meters or six times the breadth of the main transverse nave. The courtyard’s length is equivalent to four times the width of the transverse nave, or 24 meters, and its breadth is equal to the width of the nine central naves, or 45 meters. On the south side of the mosque, there is a private entrance for the imam that leads to a door on the left side of the mihrab. The original Kutubiyya Mosque also featured a special door close to the mihrab, which was utilized by the monarch to access the maqsura directly. After passing through the courtyard along the central axis, one would have entered the prayer hall through the enlarged central nave in front of the qibla wall’s mihrab niche. The prayer hall’s interior was a typical hypostyle hall, with over a hundred columns supporting horseshoe arcades that ran along to the parallel naves’ axis. This massive structure might have accommodated 20,000 worshipers. More than 100 pillars support rows of horseshoe arches that divide the hall into 17 parallel naves or aisles that run perpendicular to the southern wall, or about north to south. The pillars and arches are composed of bricks that have been plastered in white. According to Almohad tradition, the structure was likely minimally decorated. It did, however, include a number of architectural elements that were known to have been lavishly adorned. The mihrab, a niche signifying the qibla (direction of prayer), is located in the center of the prayer hall’s qibla wall (the southern wall) and is the focal point of its design. The minbar visible in the first Kutubiyya mosque was initially found in Ali bin Yusuf’s first mosque. It is a well-known example of Andalusian ornamental arts, which were patronized by Morocco’s Almoravid and Almohad kings. The minaret tower is 77 meters (253 feet) tall, including the spire, which stands at 8 meters (26 feet). The square foundation is 12.8 meters (42 feet) long on each side. From a distance of 29 kilometers, the minaret may be seen (18 mi). Inside the minaret, ramps lead to an outdoor gallery at the merlons’ level. The minaret’s body is made out of massive sandstone bricks, and the ornamental carvings around the arched fenestrations are likewise made of sandstone. The layout of the second mosque and prayer hall is identical to that of the first Kutubiyya, with the exception that each of the parallel longitudinal naves is slightly broader, resulting in a somewhat wider mosque overall. The minbar from the first Kutubiyya was stored in the second Kutubiyya for centuries, but it is no longer there. The prayer hall’s interior is now painted a bright white, with multi-toned rush mats on the floor serving as the only source of color.