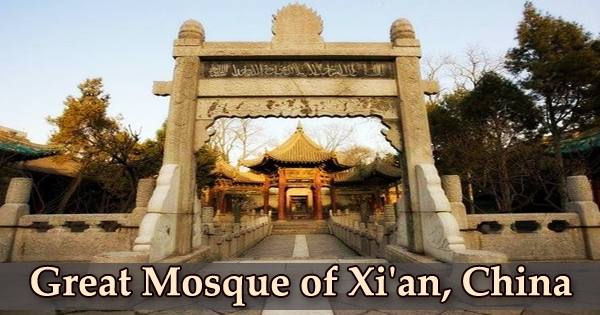

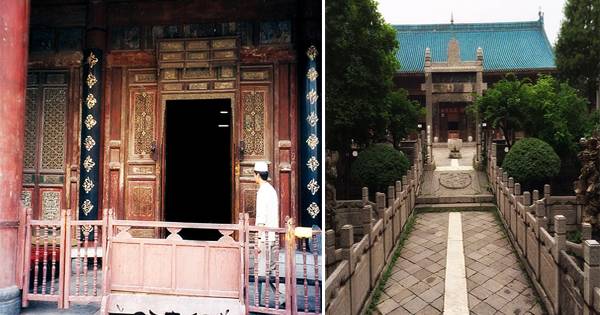

Among China’s early mosques, the Great Mosque of Xi’an (Chinese: 西安大清真寺; pinyin: Xī Ān Dà Qīng Zhēn Sì) is the largest and best-preserved. It is a form of culture for the ethnic Hui Muslim minority in northern China. It is one of China’s largest and most important Islamic centers of worship. In 1985, the Great Mosque was inscribed on the UNESCO Islamic Heritage List. Although the mosque is said to have been erected in 742 AD, it was extensively rebuilt in 1384 AD during Emperor Hongwu’s rule of the Ming dynasty, according to the Records of Xi’an Municipality (Chinese: 西安府志). With its single axis surrounded with gardens and pavilions, the mosque resembles a fourteenth-century Buddhist temple. It was built mostly during the Ming Dynasty when Chinese architectural features were blended into mosque construction. This courtyard complex is both a popular tourist attraction and a functioning place of worship within Xi’an’s Muslim Quarter. It now has almost twenty buildings in its five courtyards, with a total area of 12,000 square meters. The Great Mosque, which is larger than many temples in China, is a stunning mixture of Chinese and Islamic architecture and one of the country’s most remarkable religious places. Although the mosque was founded in the 8th century, the majority of the current structures are Ming and Qing in style. The central minaret (deliberately disguised as a stumpy pagoda) and the vast turquoise-roofed Prayer Hall (not open to visitors) at the back of the complex, both of which date from the Ming period, have Arab influences. The mosque is also known as the Huajue Mosque (Chinese: 化觉巷清真寺; pinyin: Huà Jué Xiàng Qīng Zhēn Sì), for its location on 30 Huajue Lane. Because it is located toward the eastern parts of Xi’an’s Xi’an Muslim Quarter (Chinese: 回民街), it is also known as the Great Eastern Mosque (Chinese: 东大寺; pinyin: Dōng Dà Sì). Sitting on the other side of the Muslim Quarter lies the Daxuexi Alley Mosque (Chinese: 大学习巷清真寺; pinyin: Dà Xué Xí Xiàng Qīng Zhēn Sì), which is consequently known as the “Western Mosque” of Xi’an. The mosque that stands now, on the other hand, was built in 1392, during the Ming Dynasty’s twenty-fifth year. It was reportedly formed by the naval admiral and hajji Cheng Ho, the son of a prominent Muslim family who is credited with ridding the China Sea of pirates. The mosque has been rebuilt several times since the thirteenth century. In the spring, when the white and pink magnolias blossom, it’s a lovely location to visit; in the off-season, the mosque may be a haven of quiet and tranquility in a bustling part of town.

The construction of the mosques began in 742 AD (as Tangmingsi, Chinese: 唐明寺), the first year of Emperor Xuanrong’s reign in the Tang Dynasty’s Tianbao Era, and additions were made during the Song (960-1279), Yuan (1271-1638), Ming (1368-1644), and Qing (1644-1911) dynasties, making it an ancient architectural complex representative of many periods of time. The majority of today’s structures date from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries’ Ming and Qing Dynasties. The mosque was built on Hua Jue Lane, just outside the Ming Dynasty’s city walls to the northwest of the city, in what was originally the jiao-fang area for foreigners. Today, this area is part of the city of Xian, with the city’s iconic Drum Tower just a block away. Most of the original mosques built under the Tang dynasty did not survive the collapse of the Tang dynasty and the subsequent Song dynasty. Before taking on its current form, the mosque was renovated at least four times. Around the 1260s, the then deteriorating mosque was rebuilt by the Yuan government as Huihui Wanshansi (Chinese: 回回万善寺). The mosque, which covers an area of about 12,000 square meters (14,352 square yards), is divided into four courtyards, each measuring 250 meters (273 yards) long and 47 meters (51 yards) broad. The interior is landscaped with gardens, and the further one walks into it, the more tranquil one feels. It features the layout of a Chinese temple, rather than a mosque: consecutive courtyards on a single axis with pavilions and pagodas altered to suit Islamic function. The Grand Axis of the Great Mosque of Xian, however, is aligned from east to west, facing Mecca, unlike a conventional Buddhist temple. The prayer hall is positioned at the western end of the axis and is reached through five courtyards, each with a characteristic pavilion, screen, or freestanding doorway. The mosque was designated as a Historical and Cultural Site Protected at the Shaanxi Province Level by the Chinese government in 1956. The Mosque, like virtually all other religious sites in mainland China, was briefly shut down and transformed into a steel factory during the Cultural Revolution. Religious activities resumed following Mao Zedong’s death in 1976, and the mosque was eventually designated as a Major Historical and Cultural Site Protected at the National Level in 1988. It was named one of Xi’an’s top ten tourist attractions in 1997. Arabian merchants introduced Islam to China during the Tang period. Many Muslims immigrated to China and married Han Chinese women. The Great Mosque was built at the time to commemorate China’s Islamic founders. Many more mosques have been built since then throughout the county. The Great Mosque of Xi’an reflects the Gedimu (Chinese: 格迪目, Arabic: قديم) tradition of Sunni Islam with Hanafi law, which is the main jurisprudence followed by the Hui population. Even though the Great Mosque of Xi’an’s main hall can hold 1,000 people, a typical Friday service now draws around 100 worshipers. Non-Muslim tourists, on the other hand, are not permitted to enter the prayer hall, while all tourists are welcome to visit the gardens and steles surrounding the prayer hall. The complex is divided into four courtyards that lead to the main prayer hall, which is surrounded by a fifth and final courtyard. Each courtyard has a characteristic structure, such as a pavilion, screen, or freestanding doorway, and is surrounded by luxuriant foliage. The mosque is a blend of traditional Chinese and Islamic architecture. A variety of pavilions in Chinese design are interspersed amid the mosque’s four courtyards. The mosque that still stands today is not just a religious destination for Hui Muslims in the city, but also a cultural heritage site for all people of Xi’an, illustrating Tang-era Chang’an’s enormous ethnic and religious variety. The first courtyard features a 17th-century wooden arch that is 9 meters (30 feet) tall and is decorated in glazed tiles. A stone arch lies in the center of the second courtyard, flanked on both sides by two steles. Along the north and south walls of the third courtyard are a series of chambers. Internally split, these rooms previously housed the library and the imam’s chambers, as well as a small patio for ablutions. The painted carvings of chrysanthemums, lotus flowers, and peonies adorn the paneled wooden partitions of these chambers. A large prayer hall on the fourth courtyard can accommodate over a thousand people. The rear qibla wall, which includes wooden carvings of floral and calligraphic themes, is located at the deepest portion of the prayer hall. Four bands of Quranic inscriptions encircle the mihrab, one of which is submerged in a pool of lotuses, revealing the influence of Chinese calligraphy on Arabic letters. Two circular moon gates, located behind the prayer hall, lead to the fifth courtyard, where two small manufactured hills have been built for the ceremonial viewing of the new moon. The grounds, too, are definitely Chinese, with their rocks, pagodas, and archways. The mosque’s white-capped Hui caretakers, on the other hand, serve as a continual reminder of the mosque’s Muslim function.