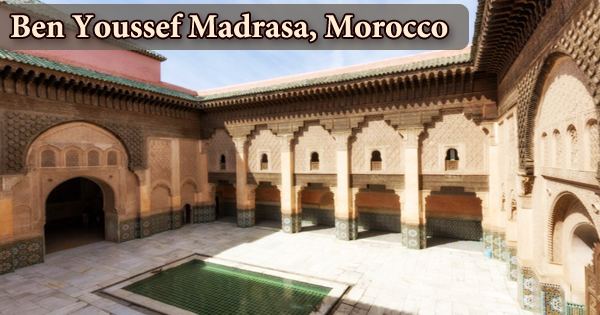

The Ben Youssef Madrasa (Arabic: مدرسة ابن يوسف; also transliterated as Bin Yusuf or Ibn Yusuf Madrasa), is named after Wattasid king ‘Ali bin Yusuf (reg. 1448-1458/851-861 AH), who ruled Morocco during the mid-fifteenth century. In Marrakesh, Morocco, there is an Islamic madrasa (college). The Ben Youssef Madrasa, which now serves as a historical landmark, was formerly Morocco’s largest Islamic academy. The madrasa takes its name from the nearby Ben Youssef Mosque, which was built by Almoravid Sultan Ali ibn Yusuf (reigned 1106-1142). The current madrasa structure was commissioned by the Sa’di (or Saadian) Sultan Abdallah al-Ghalib, and it was built in the manner of the previous Marinid period. The madrasa that exists now, however, was not established by bin Yusuf or even during his lifetime; rather, it was erected more than a century after bin Yusuf’s death by the Sa’di Sultan Sidi Abdallah al-Ghalib (reg. 1557-1574/964-981 AH). The new madrasa was erected on the same location as an older Marinid madrasa, which was likely commissioned by ‘Ali bin Yusuf, and so the Sa’di madrasa was named after the institution it replaced. Madrasas have traditionally been places of study, religion, and community engagement. Islamic schools often taught a wide range of disciplines, including literature, science, and history, in addition to Quranic Tasfeer and Islamic jurisprudence. The present ‘Ali bin Yusuf madrasa is one of the few noteworthy Moroccan madrasas established after the fall of the Marinids in 1465/869 AH, as the Marinids built nearly all of the region’s remaining architecturally important madrasas. In addition to these responsibilities, the Ben Youssef Madrasa was also one of North Africa’s largest theological institutions, with a capacity of up to 800 students. The structure, which had been closed since 1960, was renovated and reopened to the public as a historical site in 1982.

The present ‘Ali bin Yusuf madrasa has an almost perfect square footprint, measuring 42 meters long and broad in plan. In order to accommodate qibla orientation, the plan’s longitudinal axis is rotated thirty-four degrees counter-clockwise from the north-south meridian; while this rotation is similar to that of other Sa’dian religious structures in Marrakech, the true direction to Mecca would require an eighty-nine-degree counter-clockwise rotation. The structure has only one entrance, which is a tiny arched doorway on the west elevation’s northern end. The Ben Youssef Madrasa draws thousands of tourists each year and is one of Marrakesh’s most famous historical structures. The building’s plan is centered on the main courtyard, which is flanked on the upper and lower floors by east and west galleries and student residences. The courtyard, like many Islamic structures, is built on a huge shallow reflecting pool that measures roughly 3 by 7 meters. Another large chamber at the courtyard’s southeastern end served as a prayer hall, complete with a mihrab (niche symbolizing prayer direction) with, particularly rich stucco decoration. When entering the madrasa through the small portal in the northwest corner of the structure, one walks eastward down a narrow, fully enclosed corridor that runs parallel to the north wall of the structure. The act of entering the complex and the articulation of the threshold between external and inside are both carefully examined in order to achieve this moment of discovery, in which the courtyard’s magnificence is suddenly exposed and meticulously framed. The Ben Youssef madrasa’s layout is similar to that of traditional Marinid madrasas built throughout the century, with student dormitory cells arranged around the first and second floors of the central courtyard. The entrance chamber of the madrasa provides access to two auxiliary hallways that revolve around the courtyard and provide access to the ground-floor dormitories, while two stairways provide access to similar corridors on the second level. On the east and west sides, covered open air galleries border the courtyard, which is 15 meters wide and 20 meters long. Solid walls define the outside margins of these galleries, completely enclosing the courtyard and separating it from the inner hallway and student cells that surround it. The dorm rooms are also organized around a set of six tiny courtyards (three in the northeast wing, three in the southwest wing) that are accessible from these corridors on both floors. The madrasa had 130 student rooms and could accommodate up to 800 students, making it Morocco’s largest madrasa. In place of the traditional ablutions fountain, the courtyard has a huge shallow pool that is roughly 3 meters wide and 7 meters long. Only the courtyard leads to the prayer hall, which is a rectangle area 15 meters wide and 10 meters long. The building’s roof is entirely made of green ceramic tile, the usual roofing material for Moroccan madrasas. The prayer hall’s roof rises to form a pyramid above the oratory’s center, a roof portion that is also prevalent in this architectural style. The madrasa’s doors are coated in bronze and adorned with shallow carved arabesque patterns in an interlacing geometric design. An Arabic text on an arabesque backdrop is carved into the cedar wood lintel above the doors. The student quarters are sparsely decorated, but the subsidiary courtyards include ceramic tile work and carved plasterwork of comparable quality and complexity to the main courtyard. While rich and well-detailed, the ‘Ali bin Yusuf madrasa’s ornamentation is in many respects typical of fifteenth-century Moroccan madrasas, and therefore not as well-known as its unconventional layout. Sultan Abdallah is credited with building the madrasa, according to the inscription. Other inscriptions, many of which are Qur’anic passages, may be discovered on different places around the structure. The madrasa, on the other hand, has been well-maintained and is still in service today; as one of Marrakech’s most famous historical monuments, it draws thousands of architectural and religious tourists each year.