Researchers have developed a protocol for using robotic pets with dementia patients. To aid future research, the protocol employs a low-cost robotic pet, determines optimal session lengths, and identifies common participant responses to the ‘pets.’

You might think it was just another therapy session at a nursing home. A therapist places a pet carrier in a quiet room, brings out a cat, and places it on a resident’s lap. The cat purrs as the resident gently strokes its fur, and the therapist asks the resident questions about their childhood pets, eliciting long-forgotten memories.

The resident’s enjoyment of the session, as well as the benefit to their well-being, are genuine. However, the animal is not. It’s a synthetic-furred robotic pet with pre-programmed movements and sounds. However, researchers are discovering that robotic pets can be useful in therapy without some of the drawbacks and unpredictability associated with real animals.

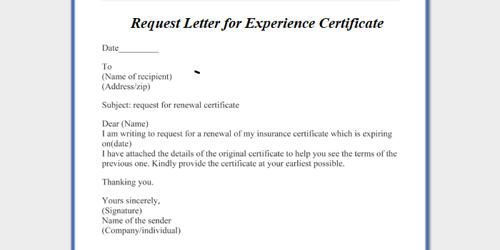

Rhonda Nelson of the University of Utah and graduate student Rebecca Westenskow developed a protocol for using robotic pets with older adults with dementia in a paper published in the Canadian Journal of Recreation Therapy. To aid in future research, the protocol employs a low-cost robotic pet, determines optimal session lengths, and identifies common participant responses to the pets.

The study discovered that when participants self-directed the session, they had the most meaningful interactions and enjoyable experiences. We always talk about providing person-centered care in recreational therapy.

Rhonda Nelson

An affordable robotic pet

Nelson has been following the development of robotic pets for the past decade, intrigued by the potential to use them therapeutically in long-term and geriatric care settings. However, until recently, the cost was prohibitive. “Having been a therapist myself and training our students to work as therapists, I’m well aware that most facilities would never be able to afford them.”

However, with the introduction of Ageless Innovation’s Joy For All Companion pets in 2015, priced under $150, widespread use of robotic pets as therapy “animals” appeared to be within reach. Robotic pets can avoid many of the risks and drawbacks associated with live animals in long-term care settings. Many facilities do not allow personal pets due to allergies, the possibility of bites or scratches, and other factors.

Researchers have already begun to study how people with dementia interact with robotic pets, Nelson notes, but haven’t yet developed a unified protocol to give, say, assisted living staff a plan to gain the most benefit from the pets’ use through directed interaction.

“There was very little information on what people were doing with the pets,” Nelson says. “So without that guidance, it’s just a toy. And what do you do with it?”

Observing interactions

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the researchers met with five people aged 82 to 87 living in long-term care facilities who had severe cognitive impairment. The researchers brought out a robotic dog or a cat (participants’ choice) in a pet carrier for two 30-minute sessions.

Throughout the session, the researchers posed questions about the participants’ previous pet experiences as well as their interactions with the current robotic pet. “Did they have dogs or cats?” Nelson explains, using examples of typical questions. “What were their names? Did they keep them inside or outside? What did they eat?”

The researchers carefully observed the responses of the participants to the pets. The robotic pets moved and made sounds, which Nelson says helped the participants engage with them.

“When the dog would bark they would say things like, ‘Oh, are you trying to tell me something?'” she says. “Or they would comment on the cat purring and would say things like, ‘Wow, you must really be happy! I feel you purring.’ One of the activities that people responded to the most was brushing the animals.”

In one case, though, the session proceeded in silence. The participant had difficulty communicating their thoughts but stayed focused on the robotic dog throughout. By the end of the session, the participant seemed to develop a connection with the robotic animal, saying “I like that dog. When he likes me.”

Nelson is frequently asked if the participants with cognitive decline understand that the robotic pets are not alive. She claims that in this study, everyone was aware that it was not a live animal.

“Interestingly, one of our participants was a retired veterinarian,” she says. “So I was very interested to see how he would interact with it.” He chose to have both the robotic dog and cat on his lap at the same time. “We would never tell someone that it was live if they asked. We would be forthright with them. We usually introduce it as ‘Would you like to hold my dog?’ and people react or respond in a way that is meaningful to them.”

Initial recommendations

Unfortunately, the COVID-19 pandemic cut data collection short. The researchers were, however, able to draw some conclusions. The activity was enjoyed by all participants, with several saying it was “extremely enjoyable.” One participant didn’t like the sounds the pet made, which was easily remedied by turning off the sound – an option that a live animal does not have.

The questions that elicited the most responses were about personal memories and tips for interacting with the pet. According to the researchers, communication with the pet is a common but unprompted behavior. “Several participants spontaneously used comments, sounds, specific inflections, and facial expressions with the pets,” the researchers wrote. “Some participants imitated the animal sounds made by the [pet] and repositioned the pet to look at its face or make eye contact.”

Although more research is needed to determine the optimal session length, the researchers noted that the 30-minute sessions in the study were sufficient. Nelson also hopes to explore how people with varying levels of cognitive decline respond to the pets, as well as how they can be used in a group setting.

The study discovered that when participants self-directed the session, they had the most meaningful interactions and enjoyable experiences. “We always talk about providing person-centered care in recreational therapy,” Nelson says. So it’s not about what I think about a particular activity. If someone enjoys it and it makes them happy, then it’s really about what they think about it.”

Why is interacting with robotic pets such a pleasurable experience? “People in long-term care facilities are in a position where everyone provides care to them,” Nelson says, “and I think it’s also psychologically very comforting for people to feel like, even though they know it’s not alive, they’re the person who’s giving love and compassion to something, and it’s responding.”