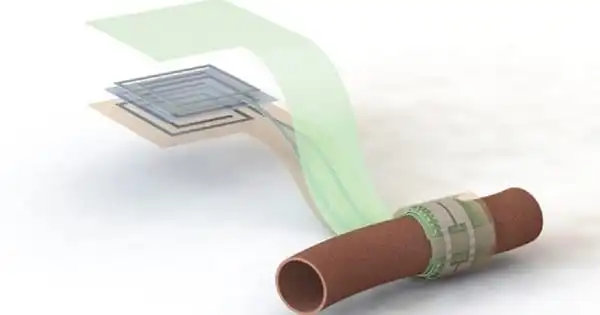

Wearables like fitness trackers, smartwatches, and other health-monitoring technologies have showed significant potential in terms of revolutionizing healthcare. However, as academics and experts in the field have pointed out, widespread adoption and integration into healthcare systems present a number of problems.

Wearable technology offers enormous opportunity to change the way we live our lives, but according to a group of worldwide researchers, the quickly evolving sector also poses significant obstacles.

The international team of scientists discusses issues facing the wearables field in a series of three editorials published in the British Journal of Sports Medicine, including a lack of standardisation of devices and data, disconnects between research and industry, and the impact of inequality in ownership.

Currently around a third of UK adults own a smartwatch or fitness tracker. A 2021 Australian-based survey reported 24 percent used fitness trackers and 23 percent used smartwatches. Some use them to track their steps, others their sleep, but few understand the potential of these devices to transform our understanding of how everyday activity influences health.

The device will detect short bursts of physical activity, such as when they run to catch a train or powerwalk to work. The use of wearable devices in study, along with quickly expanding artificial intelligence, enables us to learn how these micropatterns of daily activity connect to a person’s risk of premature death, cardiovascular disease, and even cancer.

Emmanuel Stamatakis

“If you ask someone how much exercise they did today, they will answer none if they missed the gym at lunchtime, but their fitness tracker may tell a very different story,” said Emmanuel Stamatakis, Professor of Physical Activity, Lifestyle, and Population Health at the University of Sydney’s Charles Perkins Centre, who co-led the editorial series.

“The device will detect short bursts of physical activity, such as when they run to catch a train or powerwalk to work. The use of wearable devices in study, along with quickly expanding artificial intelligence, enables us to learn how these micropatterns of daily activity connect to a person’s risk of premature death, cardiovascular disease, and even cancer.”

“It’s an exciting time to be working in this area of research. We now understand that the relationship between physical activity and health is much stronger than previous studies based on self-reported data suggested,” adds series co-lead Jason Gill, Professor of Cardiometabolic Health at the University of Glasgow.

“It is critical to use wearables as research tools because they have so much potential to inform guidelines for how much and what types of activity we recommend people do to improve their health, as well as providing new approaches to help people become more active.”

But the field doesn’t come without its challenges — all exacerbated by the pace of this technology.

“The research cycle can be lengthy, but that is not an option here.” We must adapt and move quickly if we are to capitalize on the opportunities presented by wearables – or risk missing the train,” said Professor Stamatakis, who is also launching the Mackenzie Wearables Research Hub this week at the Charles Perkins Centre, University of Sydney, Australia.

Key challenges

- Standardisation of data and devices

While most people use consumer devices like Fitbit or Garmin to track their own activity, most research studies employ research-grade accelerometers due to their consistency and scientifically proven features. Consumer electronics use proprietary algorithms that are “black boxes” to scientists. There is also a great deal of variety between brands and models, frequent model upgrades, and rigorous corporate data ownership and privacy policies.

According to the researchers, industry and academia must collaborate much more closely on uniformity in capabilities and activity data for consumer wearables to become a credible source for research measuring and monitoring of health behaviors at the population level.

- Barriers to use in health care

“There is immense potential for data from wearable devices to inform clinical decisions about risk, diagnosis and treatment. This is particularly relevant in cardiology because low physical activity increases the risk of many heart diseases, while once the disease develops it reduces the ability to be active,” said Professor Tim Chico from the University of Sheffield, lead author on the editorial on device-based measurement of physical activity in cardiovascular healthcare.

However, despite the hundreds of device models currently in use, very few are approved for clinical use by regulators. The authors write that incentives for manufacturers to obtain such expensive approvals are small compared with direct sales as “well-being tools.”

Opportunities

According to the researchers, none of these issues are insurmountable. They contend that improved incorporation of wearables in randomized controlled clinical trials and cohort research is urgently required. They recommend that regulators consider approving select devices as supplements to standard care, and that industry and academia collaborate more closely to maximize the potential of wearables for chronic disease diagnosis, prevention, and treatment – with the ultimate goal of a happier and healthier population.