Swirls, which may be kilometers long and are seen nowhere else on the planet, are visible on the lunar surface. The reason of these swirls is still unknown more than 50 years after humans arrived on the Moon, but a new piece of evidence has been unearthed that points to a more dynamic lunar environment than previously thought. The swirls stand out against the black background of the lunar “seas” as comparatively brilliant patterns (actually basaltic plains). Despite decades of research, efforts to comprehend them have made little headway, with magnetic fields, cometary collisions, and meteoroid swarms eliciting unimpressive results.

According to a report published in Geophysical Research Letters, swirls are concentrated at lower elevations, contrary to earlier observations. That gives us a big clue as to what’s causing them. The article states, “We believe this association with topography indicates for highly mobile dust movement throughout the lunar surface.” In another universe, such a discovery would be completely unsurprising. Dust might have been carried up by the wind and deposited in valleys. Wind, in the conventional sense, necessitates the presence of an atmosphere, which the Moon lacks. As a result, mobile dust need a more detailed explanation.

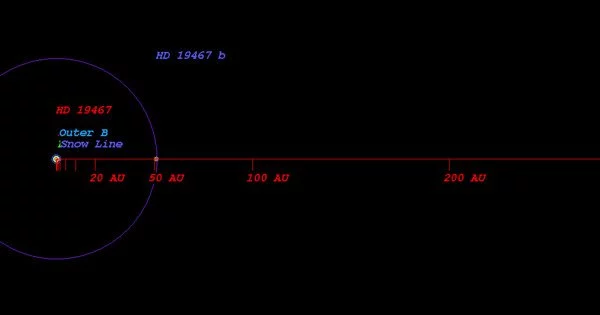

The Planetary Science Institute’s Deborah Domingue and co-authors investigated two swirls on the appropriately called Mare Ingenii (Sea of Cleverness). The position of the swirls was matched to digital elevation models in each case. These indicated that the swirls are located in topographic lows, which appear to gather dust as fine as microns. “However,” the report points out, “there must first be a mechanism for migrating lunar dust over the Moon’s surface in order to capture lunar dust grains.”

The reason, according to the authors, might be found in the solar wind, which is made up of charged particles ejected by the Sun. The electrical effects of these impacts on the lunar surface may be sufficient to lift little dust grains and keep them hanging until the upward force diminishes and gravity takes control. The lighter-colored dust particles appear to gather in lower-lying places when this happens.

On the Moon, there have previously been evidence of dust migrations. A flare 30 centimeters (12 inches) high was observed on the horizon by the lunar Surveyor missions. Both vertical and horizontal dust movement were detected by instruments left behind by Apollo 17. Nobody has looked into whether such forces were powerful enough to create patterns on the magnitude of swirls. Numerical models, however, suggest that a crater only 1 meter (3 feet) deep might gather dust grains due to the more complicated electric fields surrounding the edge, according to the scientists. Meanwhile, craters on the asteroid Eros have been discovered with “dust ponds.”

A relationship was discovered between the swirls and magnetic anomalies under the lunar crust in 1979, but the link was too faint to explain their cause. Although the link to magnetic anomalies has received the greatest attention, the article argues that magnetic impacts on the solar wind may be secondary to topography, explaining the relationship’s inconsistency. The normal sizes of dust grains in swirl and non-swirl zones, as well as the magnetic characteristics of microscopic iron particles, remain unanswered. Future Moon expeditions, which are no longer such a far-fetched prospect, may be able to provide answers.