All life on Earth depends on water, and the cycle of rain, rivers, oceans, and rain again is crucial to maintaining a stable and habitable climate. Planets with water are always at the top of the list when scientists discuss where to look for life throughout the galaxy.

According to a recent study, considerably more planets than previously believed may contain significant amounts of water, possibly even up to half of it being rock and water. The catch? All that water is probably embedded in the rock, rather than flowing as oceans or rivers on the surface.

“It was a surprise to see evidence for so many water worlds orbiting the most common type of star in the galaxy,” said Rafael Luque, first author on the new paper and a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Chicago. “It has enormous consequences for the search for habitable planets.”

Planetary population patterns

Scientists are discovering evidence of an increasing number of planets in distant solar systems as a result of improved telescope instruments. Similar to how examining the population of an entire town might show tendencies that are difficult to discern at an individual level, a bigger sample size aids scientists in identifying demographic patterns.

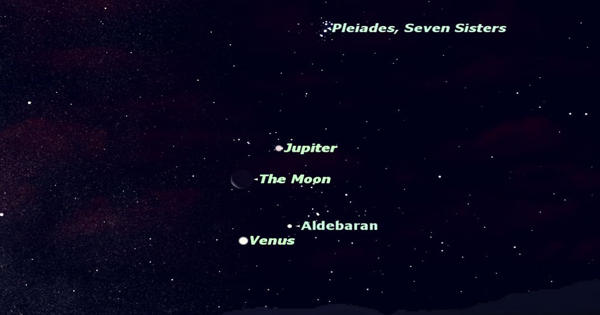

Luque, along with co-author Enric Pallé of the Institute of Astrophysics of the Canary Islands and the University of La Laguna, decided to take a population-level look at a group of planets that are seen around a type of star called an M-dwarf. Numerous planets have been discovered so far around these stars, which are among the most frequent stars in our galaxy.

However, we are unable to see the planets themselves because stars are so much brighter than their planets. Instead, astronomers spot flimsy indications of the planets’ influences on their stars, such as the shadow cast when a planet passes in front of its star or the slight tug on the star’s motion caused by a planet’s orbit. That means there are still a lot of unanswered concerns regarding the appearance of these planets.

It was a surprise to see evidence for so many water worlds orbiting the most common type of star in the galaxy. It has enormous consequences for the search for habitable planets.

Rafael Luque

“The two different ways to discover planets each give you different information,” said Pallé.

Scientists can measure a planet’s diameter by observing the shadow that is cast as it passes in front of its star. Its mass can be determined by measuring the minuscule gravitational attraction that a planet has on a star.

Combining the two readings allows researchers to understand the composition of the planet. It might be a large, airy planet like Jupiter that is primarily formed of gas, or it might be a small, dense, rocky planet like Earth.

Individual planets had undergone these examinations, but the total known population of such planets in the Milky Way galaxy had been done much less frequently. The scientists noticed a startling pattern emerge as they studied the total of 43 planets.

Many of the planets’ densities indicated that they were too light to be entirely composed of rock because of their size. Instead, these planets are most likely made up of a mixture of water or another lighter molecule and rock. Try picking up a soccer ball and a bowling ball; they are both about the same size, but one is made of much lighter material.

Searching for water worlds

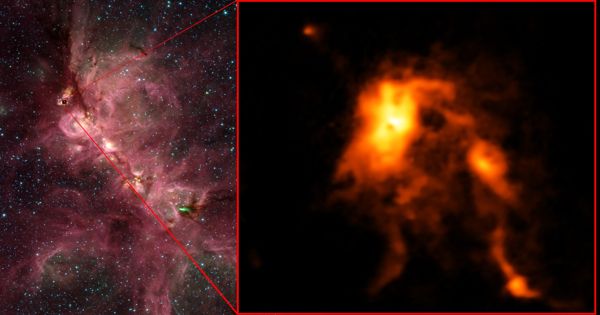

It may be tempting to imagine these planets like something out of Kevin Costner’s Waterworld: entirely covered in deep oceans. These planets are so close to their suns, though, that any surface water would be in a supercritical gaseous phase, increasing the radius of the planets.

“But we don’t see that in the samples,” explained Luque. “That suggests the water is not in the form of surface ocean.”

Instead, the water could exist mixed into the rock or in pockets below the surface. In those circumstances, the moon Europa of Jupiter, which is thought to have liquid water beneath, would be comparable.

“I was shocked when I saw this analysis I and a lot of people in the field assumed these were all dry, rocky planets,” said UChicago exoplanet scientist Jacob Bean, whose group Luque has joined to conduct further analyses.

The discovery supports an exoplanet formation theory that had lost favor in recent years, which postulated that many planets form farther outside of their solar systems and move closer in over time. Imagine ice and rock clusters coalescing in the chilly surroundings distant from a star, then slowly being drawn inward by the star’s gravity.

Though the evidence is compelling, Bean said he and the other scientists would still like to see “smoking gun proof” that one of these planets is a water world. With JWST, NASA’s recently launched space telescope that will replace Hubble, the scientists hope to do that.