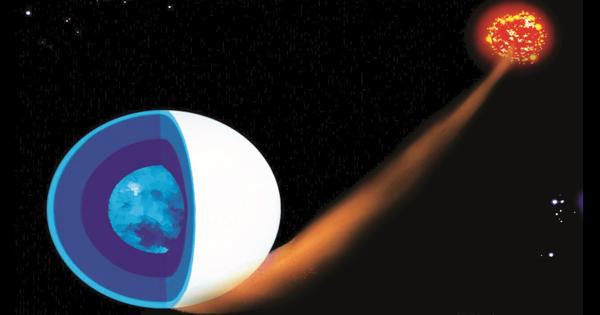

Charon, the largest of the dwarf planets, is tidally locked with Pluto and is enormous enough to be considered a double dwarf planet. It took decades for a mission to fly past Pluto, but an orbiter might swing around the tiny world in a shorter time if a fuel-saving trip can help cut costs.

Researchers have discovered that a future expedition may save fuel by using Charon, Pluto’s massive moon, for gravitational boosts, allowing for lengthy investigations of the Pluto system and potentially a visit to another frozen world in the outer solar system.

Only one hemisphere of Pluto is visible to Charon. James Christy discovered it on June 22, 1978, about half a century after Pluto was identified. It never rises or sets and always remains over the same spot on Pluto’s surface.

“With this gravitational system, Charon can take a spacecraft out past Pluto and into the Kuiper Belt,” planetary scientist Alan Stern told Space.com.

Charon and Pluto are both tidally locked, presenting the same face to each other at all times. Furthermore, Charon, like most moons in the solar system, rotates synchronously, which means it always faces Pluto in the same direction.

Stern and his colleagues at the Southwest Research Institute looked into a number of options for expanding a Pluto orbital mission while reducing fuel consumption. At the American Astronomical Society’s annual Division for Planetary Sciences conference in Knoxville, Tennessee, he presented the possibilities to his peers.

Our team has shown that the planetary science community doesn’t have to choose between a Pluto orbiter or flybys of other bodies in the Kuiper Belt, but can have both. Sometimes, you get a free lunch.

Alan Stern

“We can have our cake and eat it too!” Stern said.

NASA’s New Horizons probe unveiled Pluto in all its grandeur in July 2015. In a quick tour of the dwarf planet, the spacecraft snapped photographs and collected data without stopping, raising even more questions about the most well-known dwarf planet, such as how it can maintain geological and surface activity in such freezing temperatures.

A Pluto orbiter might investigate Pluto’s secrets and the handful of satellites that orbit it. Charon is crucial to that quest, according to recent studies.

Charon, which is nearly half the size of Saturn, might give the push needed to perform the most substantial orbital corrections during the journey, much like Titan did for NASA’s Cassini mission.

“We discovered we could do a complete orbital tour: Study all the satellites, dip down into the atmosphere … using Charon for gravity assists just like Cassini used Titan,” Stern said.

“It’s almost a zero-fuel tour,” he said, adding that fuel would only be required for small “clean-up maneuvers.”

The Pluto tour could benefit from dozens of gravity aids from Charon, according to software lead Tiffany Finley. A spacecraft might fly by each of the four smaller moons at least five times, allowing for a detailed study of Charon, examination of Pluto’s polar and equatorial regions, and even a sample of Pluto’s atmosphere.

According to spaceflight engineer and mission designer Mark Tapley, all of this would be doable utilizing an electric propulsion system similar to the one utilized by another NASA mission to a dwarf planet, Dawn.

Charon could aid the exploration of the Kuiper Belt, an expanse of ices and rocks at the frontier of the solar system. A spaceship might leave one dwarf planet and fling towards another, possibly stopping for a visit, using the gravity of Pluto’s largest moon.

“We found it is even possible to reach and then enter into orbit around a second dwarf planet in the Kuiper Belt after studying Pluto,” Tapley said in a statement about the work. Possible targets included several known dwarf planets.

Stern believes an orbiter may survive for years around Pluto, but only for three to four years before departing to explore the Kuiper Belt’s next destination. The team intends to keep publishing their findings and identifying the features of the spacecraft system required to complete a Pluto orbiter-Kuiper Belt mission.

“Our team has shown that the planetary science community doesn’t have to choose between a Pluto orbiter or flybys of other bodies in the Kuiper Belt, but can have both,” Stern said. “Sometimes, you get a free lunch.”