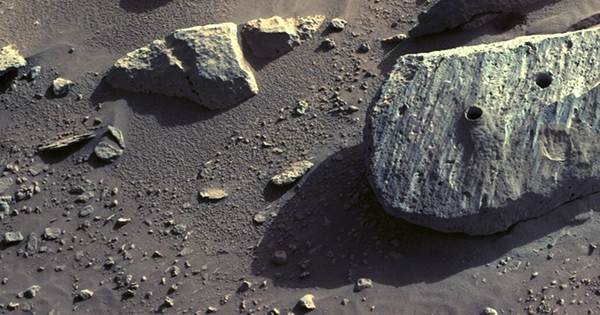

A tiny book-shaped rock is buried in the Gale Crater’s dirt, as seen in a charming new image from the Curiosity Mars rover.

The interaction of wind, water, and the human brain led to the shape. According to mineralogist Susanne Schwenzer of the Open University in England, the rocks on Mars frequently appear to be simple, rounded pebbles, despite the fact that many of their shapes suggest a dynamic history. However, some catch the sight as familiar items. As an illustration, the Curiosity rover recently photographed rocks that resemble sharp shark teeth and fragile corals.

Pareidolia refers to the human proclivity to see familiar items in ambiguous patterns. A photo obtained from the Viking I spacecraft in 1976 famously demonstrated this phenomenon on a big scale. The image appeared to reveal an unsettling face staring up from the surface of Mars. The “Face on Mars” became a cultural phenomenon and fueled conspiracy ideas about alien monuments. Higher-resolution pictures with fewer shadows later revealed a very basic mesa.

On April 15, Curiosity took a snapshot of the book Rock. It is a very small feature, measuring only 2.5 centimeters (around one inch). According to Schwenzer, this little sculpture likely dates back to the time when the sediments that makeup Gale Crater’s base were being deposited, which is approximately four billion years ago. When the area was wet, the water passed through the pores in the rocks, depositing minerals in certain places and removing them from others. According to Schwenzer, this causes unequal characteristics within the rocks, which prevents them from wearing away uniformly when the rocks erode to the point where they are on the planet’s surface and the wind blows on them. “The softer parts weather away quicker,” she claims.

Schwenzer believes that in the case of the book Rock, an old fracture may have generated the sheetlike “page” section of the structure. Fluids can migrate into fissures in rocks and deposit new minerals when they crack due to tension from sediments piled on top of them or meteorite strikes. If the minerals are tougher than the surrounding rock, they will be preserved after the rest of the rock has weathered away.

“You have at least three steps,” adds Schwenzer. “You’ve got the rock, you’ve got the formation of that harder part, and then you have the weathering.”

For the first billion or so years of its life, Gale Crater experienced both rainy and dry eras. According to Schwenzer, the last time liquid water was present in this area was about 2.6 billion years ago, and since then, wind has been responsible for all of the region’s sculpting.