In 1846, astronomer and mathematician Urbain Le Varier sat down and tried to find a planet that had never been seen before by humans. Uranus (growing up) was moving in an unexpected way, as predicted by Newtonian gravitational theory. Although the differences were small, there were differences between Uranus’ observational orbits and the way Newtonian physics estimated his orbits. In July, Le Verrier suggested that this difference could be explained by a planet other than Uranus, and previously predicted the orbit of this unknown body.

Being the first a mathematician and the second an astronomer, he was no longer interested in discovering with the help of a telescope that he had now found it in mathematics and the task of finding it was left to the German astronomer Johann Gottfried Galli. On September 23, 1846, Galileo guessed the location of the planet that Le Verrier had guessed, looked at it, and found it within 1 degree of the scene … the planet Neptune. Don’t worry, we’re going to the planet Spock.

So, discovering a new planet by looking at another’s orbit, Le Varier was asked to look for a planet whose name doesn’t even mean a butt hole: Mercury. Mercury, being very close to the Sun, is the most difficult planet to observe in our solar system (assuming there is no Planet Nine). Le Verrier was tasked with planning Mercury’s orbit using Newtonian physics. But he could not. No matter how hard he tried, Mercury’s strange orbit didn’t make sense. According to Newtonian theory, the planets move in elliptical orbits around the Sun, but observations have shown that Mercury’s orbit can vibrate to a greater extent than the gravity driven by other planetary planets.

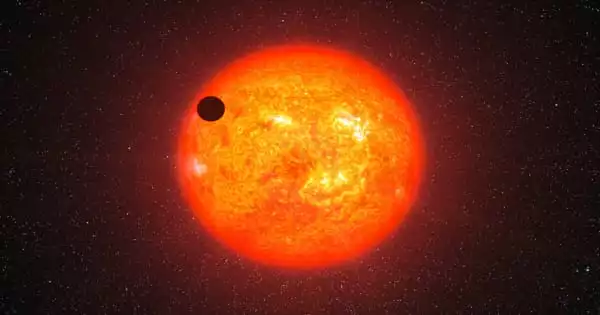

Soon astronomers began to report observations of the planet, the first being by Edmund Modesetti on March 26, 1859. Nine months later (he was, after all, an amateur astronomer) he saw an article about his work and warned Le Verrier. Based on Modest’s observations, Le Verrier calculated the planet’s predicted orbit, which he believes will transit two to four times a year. Others have reported volcanic observations, but this can be explained by observations of sunspots, known planets, and nearby stars. Le Varreier refined his calculations on the basis of other observations, yet it was in no way seen that you can describe it as concrete.