The quail is a small game bird that belongs to the family Phasianidae, which also includes pheasants and partridges. Quails are popular game birds and are hunted for sport and food. They are also raised in captivity for their eggs and meat, which are considered delicacies in some cultures.

The Toscana virus (TOSV) and the Sandfly Fever Sicilian virus (SFSV), mosquito-borne viruses that can infect domestic animals and also sicken humans, may be present in the quail.

This conclusion is drawn from a study published in the journal Frontiers in Microbiology, and which Jordi Serra-Cobo, professor at the Faculty of Biology and the Biodiversity Research Institute (IRBio) of the University of Barcelona, and Remi Charrel, leads from the Aix-Marseille University (France).

This is the first time that scientists have discovered TOSV and SFSV neutralizing antibodies in wild birds.

“To date, the reservoir for these two viruses was unknown, although they have been sought for years. Dogs and bats had been proposed as reservoirs, but the results showed that neither of them were,” says Jordi Serra-Cobo, an expert in epidemiological studies with bats as natural reservoirs of infectious agents such as coronaviruses.

The study, whose first author is Nazli Ayhan, from Aix-Marseille University, includes the participation of José Domingo Rodríguez Teijeiro, Marc López-Roig, Dolors Vinyoles and Abir Monastiri (UB Faculty of Biology and IRBio) and Josep Anton Ferreres (UB Faculty of Biology).

The quail is a migratory and also a hunter species, which enhances the potential transmission of diseases by direct contact through the food chain. In this context, regular pathogen detection is of great importance to predict future disease risks for both wildlife and humans.

Jordi Serra-Cobo

Emerging viruses in the Mediterranean basin

TOSV and SFSV belong to the Phlebovirus genus and are considered emerging pathogens. These are globular, single-stranded RNA viruses with a high rate of mutation that are spread via the bites of mosquitoes (Phlebotomus genus), which are primarily found in the warmer, drier regions of the Iberian Peninsula.

These viruses affect the majority of Western European countries along the Mediterranean Sea, as well as Cyprus and Turkey. Epidemiological surveillance, control, and prevention strategies to prevent phlebotomine sandfly bites are essential to prevent viral infections because there is no true vaccination against infection.

“Both TOSV and SFSV have been detected in a variety of domestic animals (dogs, cats, goats, horses, pigs, cows), but they can also infect humans and cause diseases,” says the researcher, a member of the UB Department of Evolutionary Biology, Ecology and Environmental Sciences.

Infections with feblovirus in people typically have no symptoms and frequently cause a three-day fever called pappatasis feve, which is remarkably similar to the flu.

“SFSV can cause a period of short-length high fever, accompanied by headache, rash, photophobia, eye pain, myalgia and general weakness. TOSV can cause the same manifestations as SFSV, but it can also be responsible for various central or peripheral neurological signs, such as meningitis and encephalitis. In fact, part of the encephalitis that occurs in summer is caused by TOSV,” Serra-Cobo notes.

Viruses in migratory birds

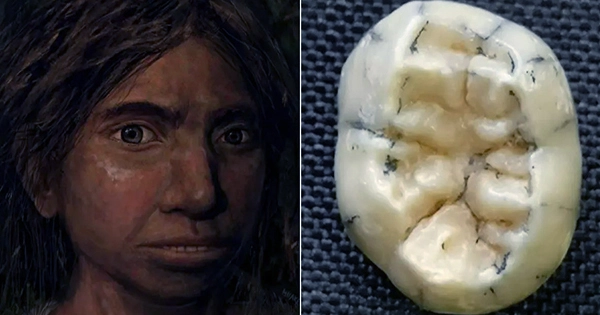

The findings of the new study imply that birds might serve as a reservoir for or an agent for propagating these viruses. Mosquitoes can contract the disease from infected birds and then bite people or other animals. In particular, the study highlights the important role of quails (Coturnix coturnix) in the infection dynamics of phleboviruses.

“Migratory birds play an important role in disease transmission due to their high mobility from one area to another, which makes them potential vectors of diseases that can affect domestic animals and human health,” Serra-Cobo stresses.

“The quail is a migratory and also a hunter species, which enhances the potential transmission of diseases by direct contact through the food chain. In this context, regular pathogen detection is of great importance to predict future disease risks for both wildlife and humans,” concludes the researcher.