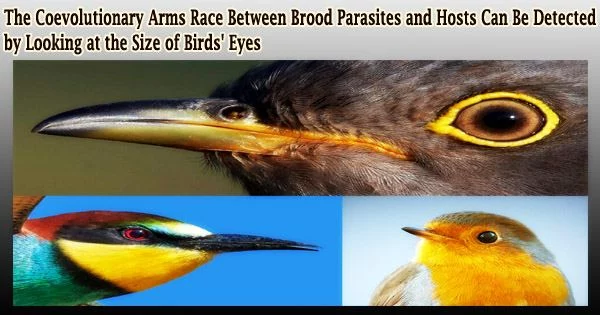

According to research published in the journal Biology Letters, eye size certainly plays a role in the struggle between avian brood parasite birds that deposit their eggs in the nests of other species and their hosts, which occasionally detect the foreign eggs and eject or leave them.

By delegating parental duties to other species, brood parasites are able to survive. The competition with the alien birds harms the hosts’ own young. Brood parasites can create more offspring than would be possible if host birds only raised their own if they are unable to distinguish eggs that are not their own.

Some bird species that brood parasites prey on are capable of identifying a foreign egg. In rare situations, these birds will enshrine the parasite’s egg by creating a new nest on top of the old one, forsake the parasitized nest, or pierce or grab the egg and eject it. This enables them to concentrate all of their parenting efforts on raising their own children.

The failure of some host birds to recognize foreign eggs in their own nests is somewhat perplexing, said Mark Hauber, a professor of evolution, ecology and behavior at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, who co-led the new research with Ian Ausprey, a recent doctoral graduate at the University of Florida department of biology and the Florida Museum of Natural History.

“Birds have much better vision overall than we do as humans. They have four color receptors instead of our three. They also can see into the ultraviolet range,” Hauber said. “What we did not know before this study was whether their eyes are adapted to egg rejection.”

The researchers used information gathered in the 1970s by Stanley Ritland, a student at the University of Chicago who measured the eyes of more than 4,000 species of birds in museum collections, to examine the connection between eye size and brood parasitism.

Birds have much better vision overall than we do as humans. They have four color receptors instead of our three. They also can see into the ultraviolet range. What we did not know before this study was whether their eyes are adapted to egg rejection.

Professor Mark Hauber

Ritland’s data was converted to digital form, and Ausprey and his associates investigated the effects of eye size on a range of attributes.

He discovered, for instance, that birds with smaller eyes tended to eat nectar or seeds that could be seen up close, but those with larger eyes were more inclined to feed on insects or other prey that would need farsightedness.

“Having larger eyes is similar to having a bigger camera lens,” Ausprey said. “By collecting more light, large eyes improve a bird’s visual acuity, its ability to resolve an image in dim conditions and at long distances.”

Ausprey discovered that brood parasites had larger eyes than host birds beyond the difference expected due to their larger body size and that birds with larger eyes relative to their overall body mass were less likely to have their nests parasitized. These findings came from an analysis of eye size in different bird species in relation to their lifestyle as hosts, brood parasites, or non-host birds.

The researchers discovered that host birds’ eyes were positively correlated with their propensity to recognize foreign eggs, unless the alien eggs closely resembled the hosts’ own eggs.

“Non-host birds tend to have larger eyes than hosts,” Hauber said. “One interpretation of that is that the parasites go for birds with poorer eyesight.”

Hauber participated in a recent study that pinpointed particular brain regions involved in interactions between parasitic insects and their hosts.

But the new research in birds is the first to show how a sensory system like the eyes contributes to the interplay between parasite and host, Hauber said.

These findings are a major step toward understanding how such interactions are evolving in birds, Ausprey said.

“Nest parasitism exerts enormous selective pressure on host populations, with major implications for population demography and local species persistence,” Ausprey said. “It’s incredible that such a simple trait as eye size can provide a powerful window into the sensory systems that mediate the coevolutionary arms race between nest parasites and their hosts.”