Forget about baby boomers vs. millennials; the generation that truly messed us off was roughly 4,000 years ago. Do you know why? We don’t have mammoths, yet they did. But we might be able to! Long-extinct animals such as the mammoth, saber-toothed cat, dire wolf, and over a dozen other prehistoric species may now be practically “brought back” because of advances in technology.

Experts from the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County and the La Brea Tar Pits, in collaboration with researchers and designers at the University of Southern California (USC), have described why and how they created this metaverse megafauna in a new paper published in the journal Palaeontologia Electronica. Dr. Emily Lindsey, Assistant Curator at La Brea Tar Pits and senior author of the study, said, “Paleoart can have a big impact on how the public, and even scientists, think about ancient life.”

Rancho La Brea, often known as the La Brea Tar Pits, is one of the most well-known instances of a “lagerstätte” — a fossil site with exceptionally well-preserved remains – in the world. It is located in the heart of Los Angeles and has been the home of paleoart for many years. There were “sculptures of saber-toothed cats, American lions, short-faced bears, and enormous ground sloths… to show tourists what the region would have looked like during the Ice Age,” according to the publication, long before the museum that presently sits there was erected. “[a] scene sculpted by Howard Ball in 1968 of a female Columbian mammoth sinking into the asphalt while her anxious partner and progeny watch on… is one of the most famous works of public artwork in Los Angeles,” according to the Los Angeles Times.

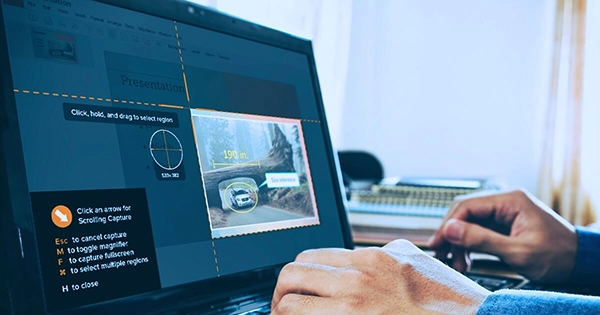

The researchers were first interested in the significance of paleoart – art that recreates or imagines extinct prehistoric species – and the influence of augmented reality on museum learning. However, they rapidly encountered a problem: no scientifically authentic Ice Age creatures had yet been developed for the metaverse. They quickly discovered that this was only the beginning of the issues with existing paleoart.

The publication notes, “The paleoart developed for La Brea Tar Pits covers a broad spectrum of scientific correctness and artistic worth.” “One painting portrays flamingoes gently swimming into asphalt ponds despite the fact that they are not known from the Ice Age or present-day California, while a recent artwork botches perspective to present-day western camels that are just half their real size.” Even the famous mammoth sculpture is deceiving, according to the writers, “reinforc[ing] the idea that creatures sank into deep asphalt pools like quicksand.” “Most asphalt leaks were probably barely a few millimeters thick, and caught creatures were more like sticky flypaper,” they write. The Lake Pit isn’t even a natural seep; it’s the ruins of an asphalt mining operation from the eighteenth century.”

Clearly, doing metaverse paleoart justice would be a massive scholarly project. “We believe paleoart is an important component of the paleontological study,” lead author Dr. Matt Davis remarked. “That’s why we made the choice to make all of the scientific research and creative considerations that went into making these models public.” Other scientists and paleoartists will be able to criticize and improve on our team’s work more easily as a result.”

The new thirteen virtual species are based on the most up-to-date scientific data, which could help to clear up some of the myths that have been disseminated by weaker paleoart. The animals move, interact with one other and even howl, despite the fact that they don’t appear lifelike. They’re built in a blocky, polygonal form to make them easy enough to operate on a regular mobile phone. “The uniqueness of this method is that it allows us to develop scientifically correct artwork for the metaverse without overcommitting to details where we still lack solid fossil evidence,” stated research co-author Dr. William Swartout.

The researchers expect that by employing academic rigor and peer review to guide artistic judgments rather than the other way around, future paleoartists will be influenced and the topic as a whole will gain more respect. They also intend to give new insights into these ancient species, and you may observe the animals for yourself by following the steps below.