Human brain cell atlases are large sets of data that try to map and categorize the various cell types and their functions in the human brain. These atlases offer vital insights into the brain’s complex cellular structure, offering light on how it works, how different cell types interact, and how changes in these cell populations can be linked to neurological and psychiatric illnesses.

Researchers have produced the most comprehensive human brain cell atlases to date. The studies shed light on several brain illnesses and provide promise for future medical advances, such as new cancer medicines.

Karolinska Institutet researchers have been involved in two simultaneous studies to create the most detailed atlases of human brain cells to date. The two research, published in Science, provide light on several brain illnesses and offer promise for future medical advances such as new cancer medicines.

Knowing what cells make up a healthy brain, where different cell types are distributed, and how the brain grows from the embryo stage is critical for comparing and better understanding how disorders originate. There are advanced atlases of the mouse brain available currently, but not of the human brain.

We’ve created the most detailed cell atlases of the adult human brain and of brain development during the first months of pregnancy. You could say that we’ve taken a kind of brain-cell census.

Sten Linnarsson

A brain-cell census

“We’ve created the most detailed cell atlases of the adult human brain and of brain development during the first months of pregnancy,” says Sten Linnarsson, professor of molecular system biology at the Department of Medical Biochemistry and Biophysics at Karolinska Institutet in Sweden. “You could say that we’ve taken a kind of brain-cell census.”

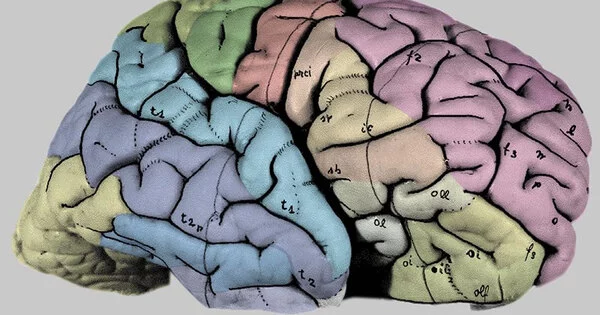

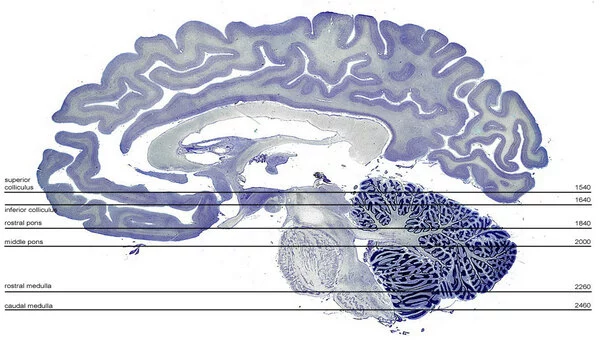

Kimberly Siletti from Linnarsson’s group led the first project. It was carried out in close collaboration with Ed Lein of the Allen Institute for Brain Science in Seattle, USA, as part of the international Human Cell Atlas program, and was based on three donated adult human brains. The researchers examined almost three million individual cell nuclei using RNA sequencing technology, which reveals each cell’s genetic identity. Overall, the researchers examined cells from over a hundred brain regions and discovered over 3,000 cell types, around 80% of which were neurons, with the remainder being various forms of glial cells.

“A lot of research has focused on the cerebral cortex, but the greatest diversity of neurons we found in the brainstem,” says Professor Linnarsson. “We think that some of these cells control innate behaviors, such as pain reflexes, fear, aggression, and sexuality.”

Groundwork for medical advances

The researchers discovered that the identification of the cells reflects the location in the brain where they first originated in the fetus, which is related to the second study. Emelie Braun and Miri Danan-Gotthold from Sten Linnarsson’s group worked with the Swedish Human Developmental Cell Atlas consortium to examine over a million individual cell nuclei from 27 embryos at various stages of development (between 5 and 14 weeks of fertilization). The findings allowed the researchers to demonstrate how the entire brain develops and organizes throughout time.

Although the results are instances of molecular biological fundamental research, the new knowledge acquired can also provide the framework for medical breakthroughs. Professor Linnarsson’s research group has utilized comparable methods to analyze various types of brain tumors, one of which was a glioblastoma, a cancer with a dismal prognosis.

“The tumor cells resemble immature stem cells and it looks like they’re trying to form a brain, but in a totally disorganized way,” he says. “What we observed was that these cancer cells activated hundreds of genes that are specific to them, and it might be interesting to dig into whether there is any potential for finding new therapeutic targets.”

Freely available brain atlases

The brain atlases will be publicly available to researchers all across the world, allowing them to compare the brain illnesses they are studying to what a normally formed brain looks like.

The investigations are part of a bigger bundle of articles published in the scholarly journal Science at the same time. The adult brain study was funded by the National Institutes of Health, while the embryo study was funded by the Knut and Alice Wallenberg and Erling-Persson foundations.