Lychees, which are bright and flavorful, were so popular that they were domesticated not just once in ancient times, but twice in two different regions of China, according to a new study. They’re prickly on the outside and sweet on the inside, and they’re well-known for their iconic pink shells and pearly, fragrant fruit. In the United States, you may come across them as a flavorful ingredient in bubble tea, ice cream, or cocktails. You can also peel and eat them raw.

Lychees have been grown in China since ancient times, with cultivation records dating back about 2,000 years. Fresh lychees were so desirable that during the Tang Dynasty, one emperor established a dedicated horse relay to deliver the fruits to the imperial court from harvests far to the south. Now, scientists have used genomics to delve even deeper into the lychee’s past. In the process, they’ve discovered insights that could help shape the species’ future.

“Lychee is an important tropical agricultural crop in the Sapindaceae (maple and horse chestnut) family, and it is one of the most economically significant fruit crops grown in eastern Asia, particularly to the yearly income of farmers in southern China,” says Jianguo Li, Ph.D., professor at South China Agricultural University’s College of Horticulture and a senior author of the study. “We were able to trace the origin and domestication history of lychee by sequencing and analyzing wild and cultivated lychee varieties. We found that extremely early-maturing and late-maturing cultivars arose from separate human domestication events in Yunnan and Hainan, respectively.”

We identified a specific genetic variant, a deleted stretch of genetic material, that can be developed as a simple biological marker for screening of lychee varieties with different flowering times, significantly contributing to future breeding programs.

Rui Xia

Additionally, “We identified a specific genetic variant, a deleted stretch of genetic material, that can be developed as a simple biological marker for screening of lychee varieties with different flowering times, significantly contributing to future breeding programs,” says Rui Xia, Ph.D., a professor in the same college at SCAU and another senior author of the study.

“Like a puzzle, we’re piecing together the history of what humans did with lychee,” says Victor Albert, PhD, a senior author of the study and an evolutionary biologist at the University at Buffalo. “These are the main stories our research tells: the origins of the lychee, the idea of two separate domestications, and the discovery of a genetic deletion that we believe causes different varieties to fruit and flower at different times.”

The study will be published on Jan. 3 in Nature Genetics. It was led by SCAU in collaboration with a large international team from China, the U.S., Singapore, France, and Canada.

A fruit so beloved, it was domesticated more than once

To carry out the research, scientists created a high-quality “reference genome” for the popular lychee cultivar ‘Feizixiao,’ and compared its DNA to that of other wild and farmed varieties. (All of the cultivars are from the same species, Litchi chinensis.)

According to the findings, the lychee tree, Litchi chinensis, was likely domesticated more than once: The analysis suggests that wild lychees originated in Yunnan in southwestern China, spread east and south to Hainan Island, and were then domesticated independently in each of these two locations.

People in Yunnan began cultivating very early-flowering varieties, while people in Hainan began cultivating late-blooming varieties that bear fruit later in the year. Interbreeding between cultivars from these two regions eventually resulted in hybrids, including varieties such as ‘Feizixiao,’ which are still very popular today.

The precise timing of these events is unknown. The study, for example, suggests that an evolutionary split between L. chinensis populations in Yunnan and Hainan, which occurred prior to domestication, could have occurred around 18,000 years ago. However, this is only a rough estimate; other solutions are possible. Nonetheless, the study provides an intriguing look at the evolution of lychees and their relationship with humans.

When will this lychee tree flower? A simple genetic test could tell

The study not only adds new chapters to the lychee’s history, but it also provides an in-depth look at flowering time, which is a crucial trait in agriculture.

“Early-maturing lychees came from different places and were domesticated independently,” says Albert, PhD, Empire Innovation Professor of Biological Sciences in the UB College of Arts and Sciences. “This is an interesting story in and of itself, but we wanted to know what causes these differences: Why do these varieties fruit and flower at different times?”

By comparing the DNA of various lychee varieties, the researchers discovered a genetic variant that could be used to develop a simple test for identifying early- and late-blooming lychee plants. The variant is a deletion (a piece of missing DNA) that is located near two flowering genes and may help to control the activity of one or both of them.

Yunnan cultivars that bloom very early have the deletion, which they inherited from both parents. Hainan varieties that mature late do not have it at all. And Feizixiao, a hybrid with nearly equal amounts of DNA from each of the two regional populations, is “heterozygous” for the deletion, which means it has only one copy inherited from one parent. This makes sense, as Feizixiao flowers early, but not extremely early.

“This is very useful for breeders. Because the lychee is perishable, flowering times have been important to extending the season for which the lychee is available in markets,” Albert says.

Sequencing the lychee genome is only the start

The SCAU team initiated the lychee genome study as part of a larger project that aims to greatly expand our understanding of the DNA of important flowering plants in the same Sapindaceae family.

“Sapindaceae is a large family with many economically important plants,” says Xia. “So far, only a few of them have had their entire genomes sequenced, including lychee, longan, rambutan, yellowhorn, and maple.”

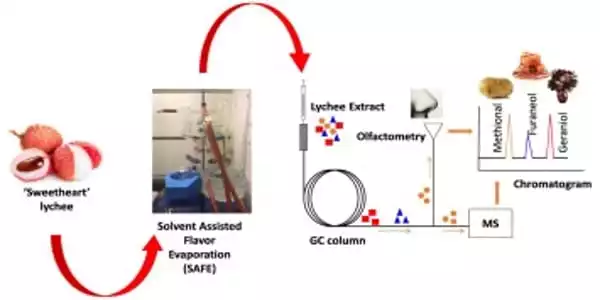

“We, at SCAU’s College of Horticulture, are working on a large collaborative project to sequence more Sapindaceae species native to China and of economic importance, such as rambutan, sapindus (soapberries), and balloon vine, with the goal of broad and thorough comparative genomics investigations for Sapindaceae genomics,” Xia adds. “Among other things, the main research interests will be flowering, secondary metabolism leading to flavors and fragrances, flower and fruit development, and so on.”