The noise characteristics of an imaging sensor can be used to verify the authenticity of a digital image, similar to how bullet scratches are used in forensic science. Photo-response non-uniformity noise (PRNU) in particular has been used in source camera identification (SCI). This technique, however, can be used maliciously to track or incriminate innocent people.

A system to analyze the noise produced by individual cameras has been developed by computer scientists at the University of Groningen as part of a project aimed at developing intelligent tools to combat child exploitation. This data can be used to associate a video or image with a specific camera.

According to the Internet Watch Foundation in 2019, the Netherlands is the leading distributor of digital content depicting child sexual abuse. To combat this type of abuse, forensic tools must be used to analyze digital content in order to determine which images or videos contain potentially harmful child abuse content. The noise in images or video frames is another untapped source of information. As part of an EU project, computer scientists at the University of Groningen collaborated with colleagues from the University of León (Spain) to extract and classify noise from an image or video, revealing the ‘fingerprint’ of the camera used to create it.

‘Every camera has some flaws in its embedded sensors, which manifest as image noise in all frames but are invisible to the naked eye. Classifiers are used in image recognition to extract information on the shapes and textures of objects in the image to identify a scene. These classifiers were used to extract the camera-specific noise.

George Azzopardi

Bullet

‘You could compare it to the specific grooves on a fired bullet,’ says George Azzopardi, assistant professor in the Information Systems research group at the University of Groningen’s Bernoulli Institute for Mathematics, Computer Science, and Artificial Intelligence. Because each firearm leaves a distinct pattern on the bullet, forensic experts can match a bullet discovered at a crime scene to a specific firearm, or link two bullets discovered at different crime scenes to the same weapon.

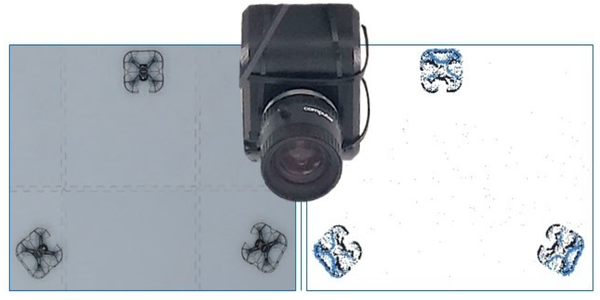

‘Every camera has some flaws in its embedded sensors, which manifest as image noise in all frames but are invisible to the naked eye,’ Azzopardi explains. This generates camera-specific noise. Guru Bennabhaktula, a Ph.D. student at the University of León and the University of Groningen, created a system to extract and analyze this noise. ‘Classifiers are used in image recognition to extract information on the shapes and textures of objects in the image to identify a scene,’ says Bennabhaktula. ‘These classifiers were used to extract the camera-specific noise.’

Law enforcement

He developed a computational model to extract camera noise from video frames shot with 28 different cameras from the publicly available VISION dataset, and then used it to train a convolutional neural network. He then tested whether the trained system could recognize frames captured by the same camera. ‘It turned out we could do this with a 72 percent accuracy,’ says Bennabhaktula. He also mentions that the noise can be specific to a brand of cameras, a type of camera, or an individual camera. In another set of experiments, he achieved 99 percent accuracy in classifying 18 camera models using images from the publicly available Dresden dataset.

His work was part of the 4NSEEK EU project, in which scientists and law enforcement agencies worked together to develop intelligent tools to combat child exploitation. ‘Each group was in charge of developing a specific forensic tool,’ says Azzopardi. Bennabhaktula’s model could be extremely useful. ‘If police discover a camera on a child abuse suspect, they can link it to images or videos found on storage devices,’ says the report.

Challenges

According to Bennabhaktula, the model is scalable. ‘By using only five random frames from a video, it is possible to classify five videos per second. Others have used the classifier in the model to distinguish over 10,000 different classes for other computer vision applications.’ This means that the classifier could compare noise from tens of thousands of cameras.

The 4NSEEK project has now concluded, but Azzopardi is still in contact with forensic specialists and law enforcement agencies in order to continue this research line. ‘We’re also working on determining source similarity between two images, which presents a different set of challenges.’ That will be the basis of our next paper on the subject.’