According to a recent study, forensics experts utilize words connected to race and ancestry inconsistently, and the field should adopt a new strategy to better take into consideration population volatility and how historical events have changed our skeletal traits.

“Forensic anthropology is a science, and we need to use terms consistently,” says Ann Ross, corresponding author of the study and a professor of biological sciences at North Carolina State University. “Our study both highlights our discipline’s challenges in discussing issues of ancestral origin consistently, and suggests that focusing on population affinity would be a way forward.”

There is no scientific basis for race; it is a social construct. In forensic anthropology, population affinity is defined by the skeletal traits connected to particular social groups. These traits are influenced by historical occurrences and causes including gene flow, migration, and other factors. Additionally, these population groups may fluctuate greatly.

This effectively indicates that race can be quite deceptive in a forensic setting. A missing person, for instance, might have had their skin tone classified as Black on their driver’s license. However, because their bone structure might have reflected other facets of their lineage, their skeletal remains might not have shown they were of African descent.

“Like many disciplines, forensic anthropology has been coming to terms with issues regarding race,” Ross says. “Some people in the discipline want to do away completely with assessing an individual’s place of origin. Others say that conventional approaches still have value in helping to identify human remains.”

“In this paper, we are recommending a third path. This study is focused on finding ways to evaluate human variation that give us valuable information in forensic and anthropological contexts, but that avoid clinging to the use of outdated defaults such as race.”

Forensic anthropology is a science, and we need to use terms consistently. Our study both highlights our discipline’s challenges in discussing issues of ancestral origin consistently, and suggests that focusing on population affinity would be a way forward.

Professor Ann Ross

In one part of the study, the researchers looked at all of the papers published in the Journal of Forensic Sciences between 2009 and 2019 that referenced ancestry, race or related terms. The goal of this content analysis was to determine if the terms were being used consistently within the field. And they were not.

“The Journal of Forensic Sciences is the flagship journal for forensic sciences in the U.S., and even there we found inconsistencies in how our field uses these terms,” Ross says. “Inconsistent terminology opens the door to confusion, misunderstanding and misuse within the discipline.”

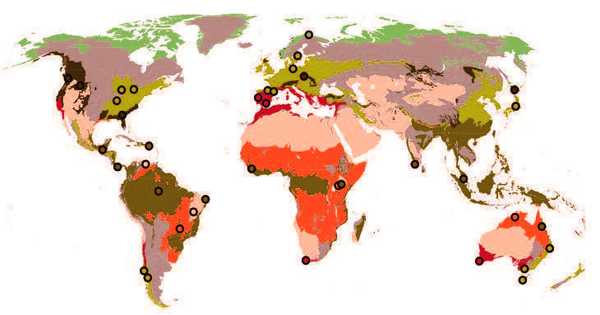

The validity of terminology like “European” or “African” to characterize the ancestry of human remains was assessed in a second section of the study using geometric morphometric data and geographical analytic techniques.

Altogether, the researchers evaluated nine datasets, comprising data on 397 people. The datasets were of human remains collected in Chile, Colombia, Cuba, Guatemala, Panama, Puerto Rico, Peru, Spain and a population of enslaved Africans that had been buried in Cuba. All of the remains, except for those of the enslaved Africans, were from the 20th or 21st centuries.

“Regarding the data we have on the remains of enslaved Africans, we want to acknowledge the value that data collected from such samples can contribute to discussions of human variation, while also noting that the history and ethics of human skeletal collections, in general, is often dubious,” Ross says. “Such body harvesting all too often occurred under the umbrella of scientific racism, without the permission of the deceased or next of kin, and disproportionately targeted marginalized populations.”

In their review of recent papers, the researchers found that forensics experts often still referred to remains as being of African, Asian or European origin.

“But our analysis of these nine datasets shows that this approach is wrong, because it’s not that simple,” Ross says.

“Let’s use Panama as an example,” says Ross, who is from Panama. “There have been huge movements of people into this area from all over the world over the past 500 years: indigenous peoples who predate colonialism, colonizers from Europe, slaves from Africa, immigrants from Asia. The contemporary remains we see in Panama reflect all of those influences.”

Ross also noted that the analysis of the nine datasets also highlighted a flaw in the contemporary idea of “clines.” The underlying tenet of clines is that populations that are geographically close to one another are more similar than populations that are geographically distant, even while there are differences between different groups of people. The researchers discovered that this presumption might be false, though.

For instance, although sharing a border, Colombia and Panama have experienced extremely diverse historical pressures in recent centuries, which is why the skeletal features of remains from those two nations are significantly less comparable than one might expect.

“All of this is important for multiple reasons, such as taking meaningful steps to reduce racism in our field, and ensuring that we are communicating clearly with each other within the discipline,” Ross says.

“It is also important because marginalized people are most often the people whose remains go unidentified. Labeling them as ‘Hispanic’ or ‘Black’ is misleading. We, as forensic anthropologists, need to change the way we think about origin. We need to begin thinking about physical markers in the context of population affinity and how we can use that to both communicate clearly and to help understand who we are seeing when we work with unidentified remains. We need to ensure that we are not contributing even inadvertently to structural inequities and racism.”

“This also means that we are faced with a wide range of new research questions. As a field, much of our work has focused on looking at data from the remains of historic populations. I think we need to begin doing more work that can help us better understand the ways in which historical events have helped to shape the skeletal characteristics of modern populations.”