Trinity College Dublin researchers recently published a study in the journal Allergy on chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU), a prevalent skin disorder characterized by recurrent hives. This is the first study to identify a relationship between uncommon cell types and treatment response. The research team was led by Professor Niall Conlon, Clinical Professor, School of Medicine and Consultant Immunologist, St James’ Hospital, as well as Clinical Lead at Ireland’s first UCARE urticaria management facility.

Chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU) is a prevalent but underreported illness in which people experience repeated, unpredictable, and severely itchy hives and skin swellings with no apparent cause. Each week, the UCARE centre at St. James’ Hospital sees 10-20 new patients with CSU. Although CSU has certain symptoms similar to food allergies, it is not caused by an allergy to food or medications. CSU diagnosis can be delayed and difficult due to a lack of understanding regarding the ailment. Furthermore, people suffering with this disease can become worried and frustrated for a variety of reasons, including difficulty at work and in interpersonal interactions, as well as sleep disturbance, poor mood, and anxiety.

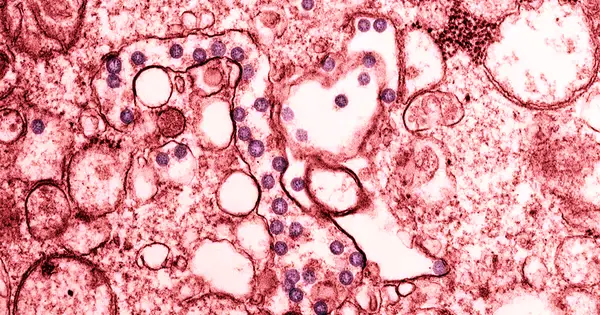

The study looked examined myeloid progenitors, a rare type of mast cell seen in the blood of patients with the illness. The researchers compared these cells in persons with CSU to healthy controls. The response to omalizumab, an anti-IgE treatment, was also examined. Individuals who responded quickly to omalizumab were found to have more myeloid progenitors in their blood than those who responded slowly (or not at all).

Our findings have significant implications not only in relation the individuals with urticaria but potentially other allergic diseases whereby we may be able to predict treatment response using exploration of this cell type.

Dr Katie Ridge

The findings suggests that these cell types could be used to predict who could respond to anti-IgE therapy.

Dr Barry Moran, a scientist at Trinity Biomedical Science Institute (TBSI), Trinity College who contributed to the study said:

‘We developed a flow assay to identify this rare cell type. We were excited to find that our findings and clinical correlates were complemented by transcriptomic data’.

David McMahon from the Irish Skin Foundation said:

“CSU refers to hives that come and go, without any particular or obvious trigger, and last for longer than 6 weeks. For some people affected by CSU the quality of life impacts can be profound and far reaching.”

CSU is frequently mistaken for an allergic reaction. Specific triggers such as allergic reactions to foods are often sought. Unfortunately, attempts to avoid suspected allergic triggers do not help. This can be frustrating for people who suffer with this condition.

Symptoms for many people with CSU can be completely controlled by regular treatment with antihistamines. Often, these medications need to be used at high doses. Some individuals will not respond to this simple intervention and will need referral to a specialist centre such as the UCARE centre in St. James’s Hospital. Individuals who do not respond to high dose antihistamines are considered for the anti-IgE biologic treatment, omalizumab. This treatment is only available in a specialist setting.

Dr Conor Finlay, a scientist from the Trinity Translational Medicine Institute (TTMI) and one of the senior authors of the study, said:

“Mast cells pack a punch, when activated by IgE antibodies they can be said to explode and release inflammatory factors into the skin – this is what causes itching and hives.”

Dr Niall Conlon a senior author on the study and consultant immunologist: said:

“For somepeople, treatment with omalizumab, an injectable drug that steadies mast cells, really works. However, for others this drug is less effective or takes much longer to work. It would really help us to understand better why certain people don’t respond as well to omalizumab. Information on how this happens might help us direct our treatments more effectively and make patients better, quicker”

Dr Katie Ridge, the lead author on the study said:

“Mast cells are tricky cells to study. Mature mast cells are not found in the blood. That is why we used a method to study an extremely rare immature form of mast cells in the blood, called mast cell progenitors. Our findings point to potential inflammatory signals in this disease and highlight how chronic urticaria is more than skin deep.

“Our findings have significant implications not only in relation the individuals with urticaria but potentially other allergic diseases whereby we may be able to predict treatment response using exploration of this cell type.”