Racetrack memory is a tentative technology under development that’s projected to offer a replacement for current memory types, including hard disk drives (HDDs) and flash. It is also known as domain-wall memory (DWM), is an experimental non-volatile memory device under development at IBM’s Almaden Research Center by a team led by physicist Stuart Parkin. It relies on the spin of electrons to move data at hundreds of miles per hour to atomically precise positions along the nanowire racetrack.

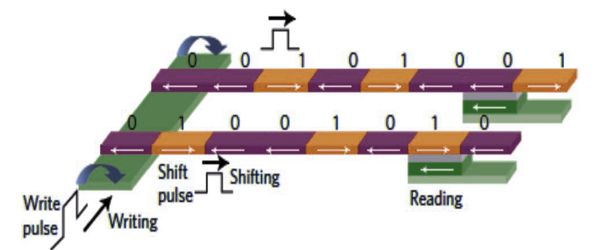

In early 2008, a 3-bit version was successfully demonstrated. It is a type of non-volatile, solid-state memory. If it were to be developed successfully, racetrack would offer storage density higher than comparable solid-state memory devices like flash memory and similar to conventional disk drives, with higher read/write performance. The data is stored as magnetic regions, also called domains, in the racetracks.

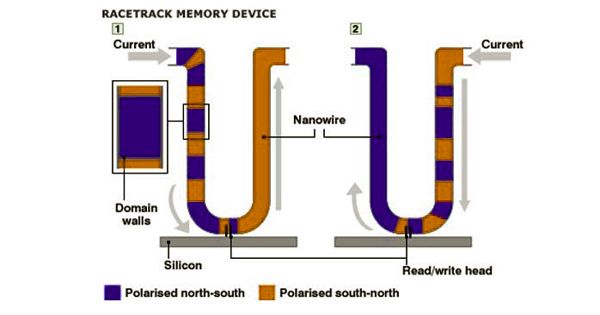

Racetrack memory uses a spin-coherent electric current to move magnetic domains along a nanoscopic permalloy wire about 200 nm across and 100 nm thick. By controlling electrical pulses in the device, the scientists can move the domain walls at speeds of hundreds of miles per hour and then stop them precisely at the position needed, allowing massive amounts of stored information to be accessed in less than a billionth of a second. As current is passed through the wire, the domains pass by magnetic read/write heads positioned near the wire, which alter the domains to record patterns of bits. However, its inventor, IBM, hopes will one day be able to hold 100 times the amount of data that can be stored on any technology that is commercially available at present.

A racetrack memory device is made up of many such wires and read/write elements. Drives with the technology could also be cheaper than flash memory, IBM hopes it will cost the same as traditional hard disk drives. In general operational concept, racetrack memory is similar to the earlier bubble memory of the 1960s and 1970s. Delay line memory, such as mercury delay lines of the 1940s and 1950s, is a still-earlier form of similar technology, as used in the UNIVAC and EDSAC computers.

Like bubble memory, racetrack memory uses electrical currents to “push” a sequence of magnetic domains through a substrate and past read/write elements. Racetrack memory uses spintronics – the inherent strength and orientation of the magnetic field produced by an electron as it spins – in addition to its electronic charge, in solid-state devices. Improvements in magnetic detection capabilities, based on the development of spintronic magnetoresistive sensors, allow the use of much smaller magnetic domains to provide far higher bit densities.

Racetrack memory is also likely to be inexpensive. Solid-state storage today is typically expensive compared to disk drive storage. Each transistor in a solid-state device can store only one bit of information. The only way to pack more information into a flash drive is to pack together with the latest tiniest, costliest transistors.

Information Source: