Some European nations have started to reduce their consumption of oil and natural gas as the ongoing Russian invasion of Ukraine continues to put pressure on the world’s energy resources. However, other nations have attempted to increase domestic fossil fuel production in order to reduce costs and alleviate their current fuel shortage.

That approach is incompatible with the carbon cuts required to achieve the Paris Agreement’s 2-degree warming objective. In order to meet climate targets, we must fundamentally alter how we produce and consume energy, which is a challenge that can only be met through energy innovation.

New analysis led by researchers at the University of California, Berkeley, and the University of Cambridge offers insight into the trajectory of energy research, development and demonstration (RD&D) that may help policymakers recalibrate their strategy to drive innovation.

The research, which was released on September 12 in the journal Nature Energy, demonstrates that participation in Mission Innovation, a fresh type of international collaboration, and escalating Chinese technological competition are the main forces behind funding for clean energy RD&D.

“By contrast, we do not find that stimulus spending after the financial crisis was associated with a boost in clean energy funding,” said Jonas Meckling, a UC Berkeley professor in the Department of Environmental Science, Policy, and Management and first author of the study.

Monitoring growth and change

Understanding whether energy innovation funding is on track to assist in achieving the emissions reductions required to achieve the Paris climate goals depends in large part on tracking the evolution and variation in “new clean” technologies, a category that includes renewables like solar and wind, hydrogen fuel cells, and improvements in energy efficiency and storage.

Oil prices can be a driver for governments to spend more on energy innovation because you want to look at alternative technologies if it’s costly to use oil. But clean energy RD&D continued to grow even after oil prices declined, which required us to think about other drivers.

Clara Galeazzi

According to estimates from the International Energy Agency (IEA), prototype technology or improvements that haven’t been fully adopted account for 35% of worldwide emissions reductions. Governments will need to invest significantly over the long term to create fossil fuel alternatives if they want to achieve net zero in the global economy.

Meckling and co-authors from Harvard University, the Chinese Academy of Sciences, and the University of Cambridge created two datasets for their analysis: one tracked RD&D funding from China, India, and IEA member countries; the other listed 57 public energy innovation institutions related to decarbonization across eight major economies. They discovered that financing for energy in seven of the eight largest economies increased by 84 percent, from $10.9 billion to $20.1 billion, between 2001 and 2018.

“But even though new clean energy funding has grown significantly, it has diverted RD&D funding from nuclear technologies and not from fossil fuel,” said Meckling.

The investigation discovered that throughout that time, funding for nuclear energy RD&D decreased from 42% of total expenditures to 24%. In particular, China, which raised its investment on fossil fuel RD&D from $90 million in 2001 to $1.673 billion in 2018, continues to heavily rely on fossil fuels for public energy RD&D.

According to Laura Diaz Anadon, a professor of climate change policy at the University of Cambridge, that level of investment in clean energy innovation is still insufficient to accomplish a significant level of global emissions reduction.

“Annual funding for public energy RD&D would have needed to have at least doubled between 2010 and 2020 to enable future energy emissions cuts approximately consistent with the 2-degree Celsius goal,” she said.

However, the authors discovered that despite the increased public investment in clean energy technology, the public institutions responsible for funding, coordinating, and carrying out RD&D are not evolving quickly enough to support rapid decarbonization. Additionally, they don’t put enough effort into commercializing sustainable energy solutions.

“While we have seen the creation of a lot of new energy innovation agencies since 2000, they experimented only marginally with designs that bridge lab to market and manage only a fraction of total energy RD&D funding,” said co-author Esther Shears, a PhD candidate in UC Berkeley’s Energy and Resources Group.

The authors also discovered that over the past ten years, developed economies particularly the U.S., Germany, and Japan have grown their funding for clean energy research and development at a faster rate than emerging ones, but China continues to be the second-largest contributor. The trend may result in a wider disparity between large economies and the rest of the globe in terms of energy innovation.

Explaining shifts in RD&D

The motivation behind the growth of public energy RD&D investment and institutional change first baffled the academics. Past analysis has focused on energy prices.

“Oil prices can be a driver for governments to spend more on energy innovation because you want to look at alternative technologies if it’s costly to use oil,” said Clara Galeazzi, co-author and postdoctoral fellow at Harvard University, who pointed to alternative energy investments following global price shocks of the 1970s and 2000s. “But clean energy RD&D continued to grow even after oil prices declined, which required us to think about other drivers.”

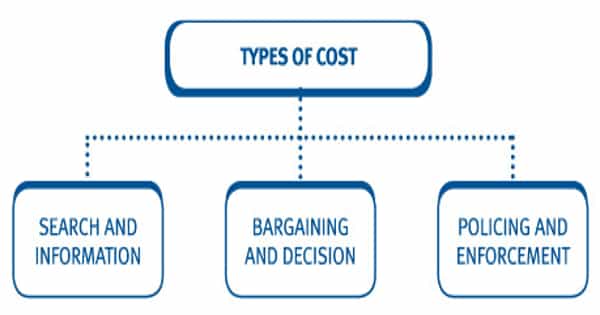

The authors examined how the “3 Cs” financial crisis, global collaboration through Mission Innovation, and Chinese technology competition altered public energy funding and institutions while tracking the last two decades of energy funding among major economies.

“We show that Mission Innovation is associated with major economies scaling their clean energy RD&D funding,” said Shears. “Technological competition with China also matters, as it creates an incentive to invest in future growth sectors where China has taken a lead including various clean energy technologies.”

After financial crises like the Great Recession (2007–2009), expenditure on stimulus programs did nothing to advance the renewable energy industry. Instead, the authors discovered that RD&D investment for nuclear and fossil fuels was frequently increased by economic recovery money. This pattern is also shown in stimulus spending during the worldwide COVID-19 pandemic’s recession.

The authors warn against taking the successful interplay of RD&D collaboration and technology competition for granted moving forward, despite the fact that international cooperation and competition have been successful in the past at pushing changes to clean energy RD&D.

“We live in times of heightened geopolitical tensions China recently announced plans to stop climate cooperation with the US,” said Meckling, adding that maintaining the balance of RD&D cooperation and technology competition requires supportive policies. “Government officials need to focus on embedding energy innovation in effective industrial policy strategies to be able to turn innovation into competitive advantages.”

“They also need to strengthen global trade cooperation to facilitate fair and open competition in clean energy technology markets that continue to incentivize governments to invest in clean energy RD&D,” Meckling said.

Co-authors on the study include Meckling; Energy and Resources Group PhD candidate Esther Shears; University of Cambridge professor of climate change policy Laura Diaz Anadon and postdoctoral fellow Tong Xu; and Harvard University postdoctoral fellow Clara Galeazzi.