One out of every three persons in the country, according to the US Centers for Disease Control, has prediabetes, a disease characterized by high blood sugar levels that may result in the onset of Type 2 diabetes.

The good news is that prediabetes can be corrected through lifestyle changes including better nutrition and exercise if caught early. The bad news? The fact that eight out of ten prediabetic Individuals are unaware of their condition increases their chance of acquiring diabetes and its complications, which can include heart disease, renal failure, and eyesight loss.

Access and cost may be obstacles to more general screening because current screening methods often require a visit to a medical facility for laboratory testing and/or the use of a portable glucometer for at-home testing. But when it comes to improving early diagnosis of prediabetes, University of Washington researchers may have hit the jackpot.

The team developed GlucoScreen, a new system that leverages the capacitive touch sensing capabilities of any smartphone to measure blood glucose levels without the need for a separate reader.

The researchers describe GlucoScreen in a new paper published March 28 in the Proceedings of the Association for Computing Machinery on Interactive, Mobile, Wearable and Ubiquitous Technologies.

The researchers’ results suggest GlucoScreen’s accuracy is comparable to that of standard glucometer testing. The team found the system to be accurate at the crucial threshold between a normal blood glucose level, at or below 99 mg/dL, and prediabetes, defined as a blood glucose level between 100 and 125 mg/dL. Using this method, glucose testing could become more affordable and available, especially for mass screenings of a population at once.

“In conventional screening a person applies a drop of blood to a test strip, where the blood reacts chemically with the enzymes on the strip. A glucometer is used to analyze that reaction and deliver a blood glucose reading,” said lead author Anandghan Waghmare, a UW doctoral student in the Paul G. Allen School of Computer Science & Engineering.

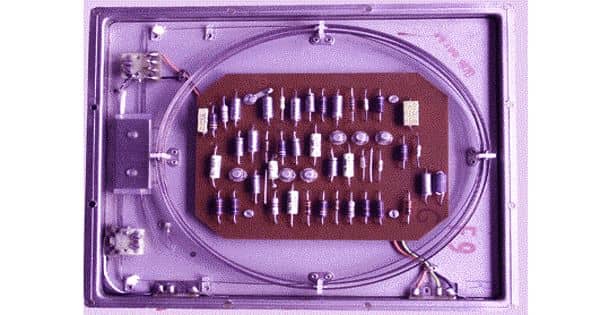

“We took the same test strip and added inexpensive circuitry that communicates data generated by that reaction to any smartphone through simulated tapping on the screen. GlucoScreen then processes the data and displays the result right on the phone, alerting the person if they are at risk so they know to follow up with their physician.”

One of the barriers I see in my clinical practice is that many patients can’t afford to test themselves, as glucometers and their test strips are too expensive. And, it’s usually the people who most need their glucose tested who face the biggest barriers. Given how many of my patients use smartphones now, a system like GlucoScreen could really transform our ability to screen and monitor people with prediabetes and even diabetes.

Dr. Matthew Thompson

Specifically, the GlucoScreen test strip samples the amplitude of the electrochemical reaction that occurs when a blood sample mixes with enzymes five times each second.

The strip then employs a method known as “pulse-width modulation” to convey the amplitude data to the phone through a series of taps at varying speeds. In this scenario, the length between taps is referred to as the “pulse width,” which is the separation between signal peaks.

Each pulse width represents a value along the curve. At a given value, the longer the space between taps, the greater the amplitude of the electrochemical reaction on the strip.

“You communicate with your phone by tapping the screen with your finger,” Waghmare said. “That’s basically what the strip is doing, only instead of a single tap to produce a single action, it’s doing multiple taps at varying speeds. It’s comparable to how Morse code transmits information through tapping patterns.”

The advantage of this technique is that it does not require complicated electronic components. Compared to more traditional communication techniques like Bluetooth and WiFi, this reduces the cost to make the strip and the power needed for it to operate. The phone is used for all computing and data processing, which simplifies the strip and lowers the cost even more.

The test strip also doesn’t need batteries. It uses photodiodes instead to draw what little power it needs from the phone’s flash.

The flash is automatically engaged by the GlucoScreen app, which walks the user through each step of the testing process. First, a user affixes each end of the test strip to the front and back of the phone as directed.

They next use a lancet to prick their finger, just as they would for a standard test, and put a drop of blood to the test strip’s biosensor. The app uses machine learning to analyze the data once it has been delivered from the strip to the phone in order to determine the blood glucose value.

That stage of the process is similar to that performed on a commercial glucometer. What sets GlucoScreen apart, in addition to its novel touch technique, is its universality.

“Because we use the built-in capacitive touch screen that’s present in every smartphone, our solution can be easily adapted for widespread use. Additionally, our approach does not require low-level access to the capacitive touch data, so you don’t have to access the operating system to make GlucoScreen work,” said co-author Jason Hoffman, a UW doctoral student in the Allen School. “We’ve designed it to be ‘plug and play.’ You don’t need to root the phone in fact, you don’t need to do anything with the phone, other than install the app. Whatever model you have, it will work off the shelf.”

The researchers evaluated their approach using a combination of in vitro and clinical testing. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, they had to delay the latter until 2021 when, on a trip home to India, Waghmare connected with Dr. Shailesh Pitale at Dew Medicare and Trinity Hospital.

Upon learning about the UW project, Dr. Pitale agreed to facilitate a clinical study involving 75 consenting patients who were already scheduled to have blood drawn for a laboratory blood glucose test. Using that laboratory test as the ground truth, Waghmare and the team evaluated GlucoScreen’s performance against that of a conventional strip and glucometer.

Given how common prediabetes and diabetes are globally, this type of technology has the potential to change clinical care, the researchers said.

“One of the barriers I see in my clinical practice is that many patients can’t afford to test themselves, as glucometers and their test strips are too expensive. And, it’s usually the people who most need their glucose tested who face the biggest barriers,” said co-author Dr. Matthew Thompson, UW professor of both family medicine in the UW School of Medicine and global health. “Given how many of my patients use smartphones now, a system like GlucoScreen could really transform our ability to screen and monitor people with prediabetes and even diabetes.”

GlucoScreen is presently a research prototype. Additional user-focused and clinical studies, along with alterations to how test strips are manufactured and packaged, would be required before the system could be made widely available, the team said.

Yet, the investigation shows how we have only just begun to fully realize the potential of smartphones as a tool for health screening, according to the researchers.

“Now that we’ve shown we can build electrochemical assays that can work with a smartphone instead of a dedicated reader, you can imagine extending this approach to expand screening for other conditions,” said senior author Shwetak Patel, the Washington Research Foundation Entrepreneurship Endowed Professor in Computer Science & Engineering and Electrical & Computer Engineering at the UW.

Additional co-authors are Farshid Salemi Parizi, a former UW doctoral student in electrical and computer engineering who is now a senior machine learning engineer at OctoML, and Yuntao Wang, a research professor at Tsinghua University and former visiting professor at the Allen School. This research was funded in part by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.