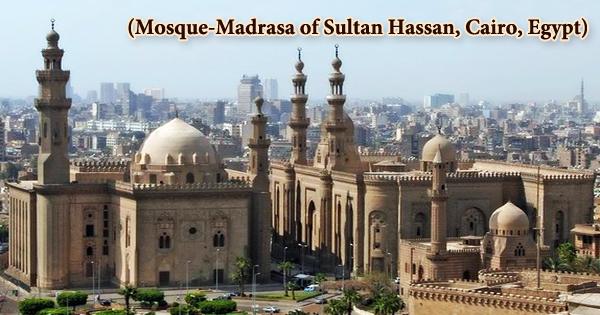

The Mosque-Madrasa of Sultan Hassan (Arabic: مسجد ومدرسة السلطان حسن) was commissioned by Sultan an-Nasir Hasan and built between 1356 and 1363 during the Bahri Mamluk dynasty; it is a massive mosque and madrasa located in the historic district of Cairo, Egypt. This enormous edifice, massive yet exquisite, is regarded as Cairo’s greatest example of early Mamluk architecture. The mosque was notable for its vast size and creative architectural elements, and it is currently regarded as one of Cairo’s most outstanding historic landmarks.

Sultan Hassan, a grandson of Sultan Qalaun, built the mosque between 1356 and 1363; he ascended to the throne at the age of 13, was overthrown and reinstalled three times, and was slain just before the mosque was completed. A dark hallway leads beyond the dramatic recessed entrance onto a tranquil square courtyard flanked by four soaring iwans (vaulted halls). The free-standing structure, which included a large domed mausoleum flanked by minarets, of which only one survives, is situated below the Citadel, toward which the colossal doorway is oriented.

The muqarnas-hood gateway stretches the length of the façade. The vertical emphasis of the facades is emphasized by the height of the outer walls and the positioning of the windows. The construction of the mosque is all the more amazing because it took place during the ravages of the Black Plague, which ravaged Cairo on several occasions from the mid-14th century onwards. Its construction began in 1356 CE (757 AH) and work proceeded for three years “without even a single day of idleness.”

The main, northern, façade, which stretches for around 145 meters and rises to a height of 38 meters, is one of the building’s most notable characteristics. The façade features a variety of stone and marble decorations, culminating in a magnificent and elegant cornice with nine levels of tiny muqarnas that resemble a honeycomb. The mosque’s prominence and scale attracted craftsmen from all throughout the Mamluk empire, including far-flung districts of Anatolia, which may explain the mosque’s design and decoration’s diversity and innovation. Limestone from the Giza Pyramids is also thought to have been extracted for use in the mosque’s construction.

The madrasas are arranged in four iwans in the middle of the design, with an ablutions fountain in the courtyard’s center and the four madrasas in the plan’s four corners. The four major schools of Sunni Islam were taught in the iwans. An extremely exquisite mihrab (niche in mosque showing direction of Mecca) is flanked by stolen Crusader columns at the back of the eastern iwan.

Even during Ottoman rule in the 18th century, the mosque was closed for several years after unrest in 1736, and was only reopened in 1786 by order of Salim Agha. However, several of these demolition attempts garnered widespread condemnation from Cairo residents, and authorities were frequently compelled to repair the damage. The portal is distinguished by an arched semi-dome ceiling with a magnificent succession of muqarnas tiers. It was influenced by Seljuq architecture (AH 429–590 / AD 1038–1194) and dates from a time when grand entrances were the norm.

The eastern façade of the mosque is topped by two minarets, the oldest of which is the southern minaret, which stands at 81.60 meters. In the style of Mamluk minarets, both minarets have a square base with two octagonal floors. In the twentieth century, the minarets were repaired. The northern minaret, which was related to the mausoleum, fell in 1659. The minaret was replaced with a smaller one with a slightly different shape in 1671-1672, and the original wooden dome of the tomb was replaced with the current dome, which was also in a somewhat different shape than the original.

The mosque is nearly 8000 square meters in size and is located near Cairo’s Citadel. The qibla iwan is far larger than the other three, which are equally massive in scale and size. It was built on the site of a beautiful palace built for one of Hasan’s amirs, Yalbugha al-Yahawi, by Hasan’s father, Sultan al-Nasir Muhammad, at considerable expense. The palace was demolished to make place for the mosque. One of the minarets collapsed during construction, killing 300 people and generating superstitious rumors that Sultan Hassan’s reign was coming to an end. They weren’t mistaken. He was assassinated by his army commander just over a month later.

The structure has a polygonal floor plan with a surface area of 7,906 sq m; the longest side is 150 m long and the shortest is 68 m. The structure is composed of stone and features a central open courtyard with an ablutions fountain in the center. Vertical rows of eight windows (distributed across four storeys within) characterize the building’s southwestern and northeastern facades (its longer sides), which are a distinctive feature that helps to visually accentuate the structure’s height.

The triangular gaps above the lower windows were formerly filled with geometric ceramic decoration, presumably inspired by Anatolian Turkish architecture. The mosque proper is encircled by four iwans that circle the courtyard. A madrasa can be found in each of the building’s four corners, each of which teaches one of the four schools of Muslim religious jurisprudence (fiqh). A set of stone corbels extending from the wall toward the bottom of the southwestern wall, below today’s street level, apparently functioned to support the roof of a covered market along this side of the street.

Rather of being integrated into the center area, the students’ cells were distributed along the street facades, and their windows are an important element of the façade architecture. The madrasas were reached through doorways in each of the four iwans’ corners. Each madrasa has a central courtyard with a fountain and an iwan in the center, as well as three storeys of student living quarters. The mausoleum chamber on the southeastern side of the mosque is flanked by two minarets now.

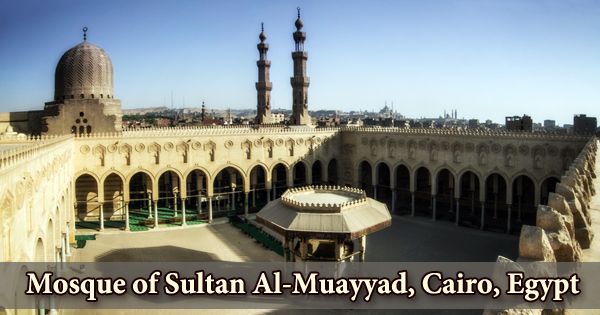

Two further minarets were initially planned to stand above the mosque’s colossal doorway, similar to the architecture of Mongol Ilkhanid and Anatolian Seljuk madrasas and mosques about the same time. The construction was influenced by the phenomena of madrasas, which were built with the objective of teaching religion according to Sunni schools of law, digging deeply into the knowledge and teachings of Islam. Sultan Mu’ayyad forcibly purchased the original bronze-covered entrance doors for use on his own mosque in the early 15th century, and they may still be seen there today.

The structure includes a mausoleum with ornate decorations, where the builder’s son, Shihab Ahmad (d. AH 788 / AD 1386) is buried. The mausoleum is square in shape, with sides of 21 meters in length and a 48-meter-high dome. Although the building’s outer walls are made of stone, much of the inside is made of brick, with stucco facades and masonry for decorative accents. This mausoleum’s marble mihrab is adorned with intricate marble mosaic geometric ornamentation.

Despite the chamber’s massive buttressed walls being able to hold something heavier, the mosque’s original dome was similarly made of wood. The original dome, on the other hand, had a totally different shape. It was characterized as having the shape of an egg by an Italian traveler in the early 17th century; more specifically, it began narrow at the bottom and expanded up like a bulb before ending in a pointy tip. The edifice was almost finished when Sultan Hasan died in AH 762 / AD 1361, with the exception of some supplemental work undertaken by Bashir al-Jamdar. The marble wall revetment and marble floors, the dome of the courtyard fountain (finished in AH 766 / AD 1364), and the two great door-leafs belonging to the copper doors that can presently be found in the Mosque of al-Mu’ayyad Sheikh were all part of these works.

Information Sources: