Life in the Village

Milton, in his l’ Allegro, gives us a pleasant picture of life in a village. Though he speaks of England, his description with minor changes is true of villages all over the world. A man in the village gets up early in the morning with the welcoming song of birds. He greets the sun as it rises in a state on the eastern horizon. He listens to the songs of the peasants and watches the cowherd drive his herds to pasture. In the afternoon, the ‘neat-handed’ farmer’s wife serves her husband with a simple food she herself has cooked.

He sits him down, the monarch of a shed:

While his loved partner, boastful of her board,

Displays her cleanly platter on the board.

In the evening, the children and younger people play in the open fields, while their fathers and grandfathers look on with lively interest. Then at the close of the day they sit and talk and tell stories, and after a frugal meal retire early to bed and to a peaceful slumber. And all through the day, one feels the fresh breeze and fragrant flowers and the sweet tunes that hover in the air.

Quiet and peaceful such a life undoubtedly is. It is almost an ideal life for many. it calls the heart to quietness. Indeed, “to one who has been long in city pent”, says Keats “It is very sweet to look into the fair and open face of heaven.” The loveliness of nature is a poem in itself that one may read without tiring. There are some also who may hate the vulgar rusticity of the country, but none the less they love its silence and quietude and restful calm. Above all, the lover of nature will like nothing better than to vegetate in a world of vegetation, “when I am in the country”, says Hazlitt, “I wish to vegetate like the country.”

All this is true, and for a change from the busy hum of towns, nothing can be sweeter or more inviting than the quiet repose of rural life. Yet few who have tasted the life of the city will feel inclined to go back to the village in spite of all its healthy and healthful attractions. For one thing, life in the village is too monotonous and unexciting. For one thing, life is the village is too monotonous and unexciting. A man slips into a familiar groove and forgets to be bold and adventurous. “His face”, said Sydney Smith, “it perpetually turned towards the fountain of orthodoxy.” His attitude to life is conservative. He begins to dislike change, and he thinks to live is conservative. He begins to dislike change, and he thinks it a virtue to stick to the ways of his fathers. The range of his mind is bound by routine and limited by tradition. He cultivates fixed habits, clings to old customs. Perhaps that is the reason why a village society is so easily and so often a victim of petty bickering, and of narrow-minded jealousies. Johnson said that in a village “every human being is a spy”, which is capped by Hazlitt’s remark: “All country people hate each other.” The general attitude is critical and fault-finding. All who have read Saratchandra’s Palli Samaj know how true this is.

No doubt much of this distaste for the village life in our country is due to the condition of the villages. The absence of the modern amenities of life is intolerable to us. Hence in modern times, many are trying to reconcile the best elements of the village and the town “the country is a lyric, the town is dramatic. When mingled the make a perfect musical drama,” – by these words Longfellow meant that the country ministers to our feelings, but the town excites our passions. To combine the two, we need a town in a rural setting. It must not be too crowded with men; the houses must be situated in pleasant leafy surroundings. There must be plenty of open space-parks and playgrounds and swimming pools. And whenever one wishes, one can wander away from the city and be in a moment in the heart of open corn-fields, and gardens, and orchards. Thus to nature’s amenities of space and light and fresh air will be added electricity, gas, and the various municipal amenities offered by a modern city. These are called ‘garden cities’ and they aim at a fruitful synthesis of town and country.

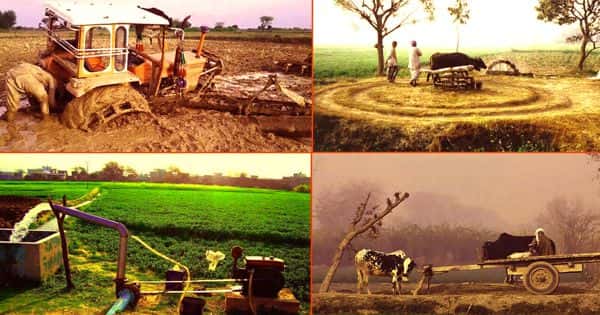

After independence, like everywhere else, our villages also have undergone basic changes, though ever so slowly. The key to real improvement lies in the extension of electricity to the villages. In this direction, the multipurpose hydro-electric power stations have been helping progress in many ways. Perhaps Punjab has made the most striking progress in electrifying all its villages but works on similar lines are being carried out in other states. Co-operative farming is being encouraged, though old traditions of our farmers are standing in the way of rapid progress. Motor-pumps have been introduced to draw water from deep tube-wells to irrigated lands. Power-driven tractors have leaped farmers cultivate lands on a co-operative basis. They have opened up opportunities for our young men to start small-scale units to manufacture spare parts and carry on repairs locally. The growth and extension of these will change the outlook of our village communities electricity is being gr gradually carried to the villages, which will increasingly enjoy the benefits of lighted-up roads and households. Roads are also being extended, and regular bus services are making transport of men and materials cheap and easy.

Naturally, with these, our villages are no longer sleepy hollow but are humming with life. Many will perhaps look back nostalgically to the quiet peaceful rural life of the past, but there is no doubt that life in the villages today is no longer stagnant and monotonous as it used to be in the past.

The transformation of the villages is perhaps not as rapid as many would like it to be. Efforts must be made to accelerate the tempo of progress. For this, each village or group of villages in a locality should be encouraged to develop its own identity. Educated young men with idealism and initiative should organize themselves into pantalets or smites and plan outlines of further development. The schools should form the central parts or starting points, to receive additions, and instead of being set to the same pattern, they should try to lay emphasis on the occupation and outlook dominant in that locality. Rural plans thus formed should be pressed forward to the government; their feasibility tested and modified by a central body of experts and finally financed by proper authorities. In other words, the responsibility and the effective authority should be decentralized so that each unit may be a vital center of activity. Small research laboratories should also be set up in rural areas to help farmers and industrial workers. Villagers will not prosper until they are encouraged to think and plan for themselves instead of being passive agents of some remote central authority.