Introduction:

The ICPD Conference endorsed women’s rights to decide freely and responsibly the number, spacing, and timing of their children, and to have the information and means to do so1. Emergency Contraception provides an additional option to realize these rights.

Emergency contraception (EC) occupies a unique position in the range of family planning methods currently available to women. ECs enable women to prevent pregnancies after they have an unprotected sex. Thus it averts unplanned and unintended pregnancies, which in turn, reduces unsafe abortion women resort to for unwanted pregnancies. Emergency contraception there fore is an element of reproductive choice for women in a situation where women in a situation where women may have little control over their sexual lives.

Although emergency contraception has been available for close to three decades, it’s potential to reduce unintended and abortion has begun to be realized but recently. The experience of countries in South and East Asia shows that emergency contraceptives are simple to use, relatively inexpensive, and in many cases, already accessible to the women who need them. The major constraint or obstacle to use of these methods is lack of information, not only among the women who are the users, but also the service providers. Because country level information is lacking, clinical and behavioral research is needed to design effective strategies to enhance availability of information and services for women. By reducing the number of unwanted pregnancies, emergency contraception can greatly reduce the need for abortion3.

Emergency contraception ought to become an established option in the range of family planning methods available to women. Furthermore, emergency contraception may well fill up an important gap among groups whose needs have gone unmet by traditional family planning4.

Despite the availability of highly effective methods of contraception many pregnancies are unplanned and unwanted as well current methods of contraception sometimes fail, ECP is a important backup when routine contraception fails to work properly, as when a condom breaks or a diaphragm or IUD becomes dislodged. These pregnancies carry a high risk of mortality and morbidity, often due to unsafe abortion. Many of these unplanned pregnancies can be avoided using emergency contraception. More over offering- emergency contraception is an important way by which family planning and reproductive health programs can improve the quality of their services and better meet the needs of their clients. Emergency contraception is needed because no contraceptive method is 100 percent reliable and few people use their methods perfectly each time they have sex5 –

Some where between 10-22 million abortions are performed annually illegally all over the world excluding Europe and North American. Undoubtedly many of these women would have been eligible for emergency contraception and would have accepted and preferred such a procedure if it were available to them. Abortion mortality has been estimated to be between 67,000 to 2,04,000 per year in developing countries4.

In many developing countries induced abortions are illegal and consequently clandestine abortions are often performed. Reducing the need for abortion in such circumstances would reduce abortion-related mortality and morbidity and other negative health effects of such procedures. In many developing countries the consequences of unintended pregnancies are more detrimental to the health and well-being of women than in developed countries. Emergency contraception if easily available and widely used can prevent a significant number of unwanted pregnancies. Thus Emergency contraception can be potentially life saving under such circumstances. It may be notable that more than half of the currently married women in Bangladesh are not using any methods2 and nearly 40 percent of the contraceptive users stop using contraception within 12 months of starting, due to side effects and methods failure. Also, much alarming as it may seem, approximately 8, 00,000 abortions are estimated to occur each year in Bangladesh. They contribute to one quarter of all maternal deaths in this coutry. Abortion services which are often costly, poor in quality, sometimes enhancing risk of RTls and HIV and even forge life threatening conditions. Statistics also show that about 52,000 women are treated in the hospitals annually for abortion complications of induced abortion and another 19,000 are treated for complications resulting from menstrual regulation procedures. There is no doubt that many of these abortion related deaths could have been avoided of women had easy access to emergency contraception.

If the use of emergency contraception is to have a significant impact on the abortion rate then it must be made easily available as well as knowledge about it should be disseminated.

Therefore, the introductory process should ensure that ECP are included in a program’s overall family planning training materials/curricula information, education, and communication (lEG) materials; and logistics and distribution systems. –

Background

A population of more than 120 million makes Bangladesh the ninth most populous country in the world. The relatively young age structure of the population indicates rapid population growth in the future. At present approximately 37.5 million women are within 10 to 49 year of age group and among the 22.8 million is currently married9. The young structure constitute a built in “population momentum” which will continue to generate population increases well in to future, even in the face of rapid fertility decline. Even if replacement level fertility is achieved by the year 2007, as targeted by the government policy, the population will continue to grow for next 40 to 60 years.

The policy to reduce fertility rates has been repeatedly reaffirmed since the independence of Bangladesh. All subsequent government that has been come in to power has identified population control as the top priority for government action. Bangladesh has formulated three years national Health and Nutrition and population program (HNPP) with an objective to ensure universal access to the essential health care services of acceptable quality and to further slow population growth. The most important basis of HNPP is reduction of maternal mortality and morbidity and reduction of fertility to reach replacements level fertility by the year 2007.

According to BDHS 2000-2001, 54% currently married women in Bangladesh are currently using contraceptive method. Modern methods (pill, intrauterine contraceptive device, indictable, Norplant, e.g. 43%) are much preferred over traditional method (periodic abstinence, withdrawal, lactation amenorrhea method etc. 10%). The contraceptive prevalence rate has increased almost seven folds since 1975 from 8% to 54% of married women. Most of these increases have been in use of modern methods and pill is the most widely used methods.7

Despite of relatively high and increasing level of contraceptive use, available date indicates that unplanned pregnancies are still common. Approximately 28000 maternal deaths occur every year in Bangladesh due to pregnancy and delivery related complications, while may more women suffer major – physical and psychological injuries. Available statistics indicates an increase in Menstrual Regulation (MR) and abortions and most of these are performed by untrained practitioners under unhygienic conditions. The official estimates indicate about 1,20,000 MR/abortions11. These MR/abortions result in serious maternal morbidities and or deaths according to Kamal (1993), approximately 8000 women in Bangladesh die each year due to abortion relatect complications.

In Bangladesh major thrust of the family planning program has been on methods that needed to be used in a continuous basis. The concept of emergency contraception is relatively new in Bangladesh. Despite availability of the methods that can be used as EC there has been very little effort to offer women with emergency contraception, as a choice to prevent unwanted or un timed pregnancies. Very recently a brand of EC product has been marketed by private sector and made available through pharmacies without proper lEC. activities13. Although about 49% women are currently using contraceptives, it must be acknowledged that there is still an unmet need especially among newly weds, adolescents, and for women who are in prolonged separation, living away from there spouse who often do not use any contraceptive method. These factors among with women’s lack of reproductive awareness and power in sexual decision making results in unplanned pregnancies undertake life threatening measures to terminate the pregnancies. In such a scenario emergency contraception can be a valuable reproductive option.” It should also an essential part of treatment of women who are victims of sexual assault.

Justification

In Bangladesh, about 1.2 million births are unplanned and its estimation is approximately 31 percent of total birth. It is also observed that 28 percent of estimated deaths are due to abortion related complication. ECP does not induce any abortion. Infect it helps in reducing number of abortion14. A recent WHO publication indicates that use of ECPs could reduce the induced abortion rate as

much as 50%15 .

In Bangladesh adolescent represent a particularly important group and we should consider that they could benefit from EC. About 50% of adolescent girls aged 15-19 in Bangladesh are married and one quarter of them are mothers. Adolescent are more likely to have high risk pregnancies and unintended pregnancies.

Unsafe abortions also leave behind hundreds and thousands of women with long-term health problems including infertility. Treating complications of unsafe abortions can place major strain on the often-meager health budgets of many developing countries. In such situations emergency contraception can be of great importance as it reduces the number of unwanted pregnancies which in turns greatly reduce the need for abortion16.

Emergency contraception if highly aware, easily available and widely used can prevent a significant number of unwanted pregnancies. In many developing countries the consequences of unintended pregnancies are more detrimental to the health and well-being of women than in developed countries. Emergency contraception can be potentially life saving under such circumstances.

Unintended pregnancy is a major public health problem that affects not only the individual directly involved but also society. Insures in both the public and private sectors generally cover the medical costs of unintended pregnancy outcomes, with coverage for abortion showing the most variation. Extending explicit coverage to emergency contraception would result in cost savings by reducing the incidence of unintended pregnancy.

Emergency contraceptives are simple to use, relatively inexpensive, and in many cases, already accessible to the women who need them. The major constraint or obstacle to use of these methods is lack of information. Because country level information is lacking, clinical and behavioral research is needed to design effective strategies to enhance availability of information and services for women. Therefore in Bangladesh there is an urgent need to sensitize- the policy makers, program managers, service providers and researchers regarding emergency contraception.

So therefore, this independent study is planned to carry out to help to know the level of knowledge about the ECPs among the women of reproductive age which in tern helps the above mentioned personnel. More over, this sort of study, as far known, was not done previously in the place of study. There is no scope of ethical, political and social conflict by this study rather might be acceptable to the proper authority. Besides, this study can be done within the allocated time given.

Research question:

What is the level of knowledge regarding Emergency Contraceptive Pill among eligible women?

Objectives:

- General objective:

To asses the level of knowledge on ECP among married eligible women.

B. Specific Objectives: –

1. To estimate the proportion of respondents’ knowledge emergency contraception.

2. To find out the socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents.

3. To know the knowledge about correct use of ECPs.

4. To know the- source of information of ECP.

C. Ultimate Objectives:

To reduce unwanted pregnancies and its consequences

Key variables –

Dependent Variable:

Level of knowledge on ECP among married eligible women

Independent Variables:

A. Variables related to socio-demographic and economic characteristics:

1. Age

2. Marital status

3. Religion

4. Occupation

5. Educational status

6. Monthly family income

7. Number of children

8. Duration of marriage life ~ —

9. Live with husband.

B. Variables related to knowledge of ECP of the respondents:

1. Name of ECP

2. Knowledge of indication of ECP a

3. Knowledge of dose of ECP

4. Knowledge of timing of ECP

5. Knowledge of interval of ECP

6. Knowledge regarding effectiveness of ECP.

7. Knowledge regarding side effects of ECP.

8. Knowledge regarding the availability of ECP

9. Knowledge regarding the source of information of ECP

10. Use of ECP

Operational definitions:

Emergency Contraception

Emergency contraception (BC) refers to contraceptive methods that can be used by women in the first few days following unprotected intercourse to prevent an unwanted pregnancy.

Emergency Contraceptive pills:

Emergency contraceptive pills (ECPs) are hormonal methods that can be used to prevent pregnancy following unprotected intercourse.

Non- accepters of Emergency Contraception

Women who never used Emergency Contraceptive Pills (ECP).

Educational status:

Educational status of respondents was categorized as follows:

Illiterate

Women who could not write or read.

Primary (Class l-IV)

A woman who has passed between class one to class five.

Secondary (Class Vl-X)

A woman who has passed between classes six to class ten.

S.S.C

Who has passed the S.S.C or equivalent examination.

H.S.C

Who has passed the H.S.C or equivalent examination.

Monthly family income:

Monthly family income of the respondent means the total money earned by all the members of family from all available sources in one month.

Limitations of the study:

This cross sectional study was conducted at Azimpur maternal and Child Health Training Institute (MCHTI), Dhaka to find out the level of knowledge on emerge contraception among women of reproductive age. The study is not beyond limitations. The limitations those were perceived while conducting the research are as follows:

1. The place (MCHTI, Azimpur, Dhaka) was selected purposively. The finding might be area specific and might not necessarily represent the national situation.

2. The sample size of the study was small to represent the situation prevailing

nationally.

3. There was also chance of recall bias in data pertaining to knowledge as well as practice on emergency contraceptive pills.

Literature Review:

Only a few numbers of studies on assessment on the Emergency contraception has been done in Bangladesh as well as in other countries all over the world. Some of the findings of selected studies on Emergency contraception situation are presented in the chapter followed by some socio-demographic determinants of the respondents. So far known, there was a few studies had been carried in Bangladesh but a lot study was done in abroad. Objective of these chapters is to discuss some of the findings of the previous studies, to critically review the methodologies, to find out weakness and strengths of the studies and the problems the researcher faced so that the present study can be enriched by and guided by these past experiences.

Emergency contraception:

Emergency contraception although first use in the 1960s, after four decades it still remains a largely unknown method. A variety of hormonal contraceptives ( high doses of ordinary birth control pills, high doses of mini pills, Progesterone only preparations) and copper intra-uterine devices QUD), Danazol RU 486 have been identified as emergency contraception19.

Global Situation:

Although it has taken more than a decade to promote widespread knowledge of emergency contraception, today, it is sold in more than 20 countries around the world. Nonetheless over the past two years the so-called “morning after pill” has first contraceptive to become more accepted, thanks to the development of better products with fewer side effects. France was one of the first countries to approve sales of emergency contraception. Today, the almost entire European Union, Canada, the US, some Latin American nation, including Brazil, Argentina Cuba, Jamaica, Uruguay distribute different forms of EC, either over the counter or with a medical prescription. Telephone hotline providing information on emergency contraception is increasingly common. By approving EC, Spain authorities hope to reduce the rate of pregnancy among the adolescent, the sector of population that is least likely to use protection during sexual relations. In Brazil and many other countries EC is a part of treatment protocol for women victims of sexual violence.8

The level of availability and use of postcoital or emergency, contraception varies widely depending upon the prevailing relevant regulation and policies, providers’ and women’s understanding of and attitudes toward it and cost. At present in the Netherlands and the UK, postcoital contraception is an accepted and important part of family planning practice, well known among both physicians and women at large. In Mexico and Nigeria, awareness of emergency contraception remains low among both health care providers and the pub~c.4

Situation in Asia:

In Malaysia, where abortion is strictly regulated, emergency contraceptive methods are marketed legally, but family planning organizations avoid offering them. In China, emergency contraception has long been offered by the government family planning service, but they have not been separated into methods advocated for emergency use only and those recommended for ongoing use4. There is no published data on EC use in India. There is very little awareness about EC, not only among the public but also among the service providers20. In Jakarta, knowledge of health providers on emergency contraception is still low or limited21.

Bangladesh situation:

In a study paper recently presented in Population Council showed that, only few providers were familiar with emergency contraceptive pill, and had accurate information about side effects and indications22.

The Directorate of Family Planning in collaboration with the Population Councils

Frontiers in Reproductive Health Project, Pathfinder International and John Snow Inc (JSI) was conducting a feasibility study to develop” test and document operational details for introducing emergency contraception as a’ back-up support for existing family planning methods. The analysis of the qualitative data revealed that people do not have any knowledge of emergency contraception. And substantial number of women practice harmful traditional methods to protect them from unwanted pregnancies22.

Knowledge of ECP

The knowledge of women concerning EC is improving in many countries; however better knowledge is not always the same as better attitude and advanced practice.

In 1995 a small survey of 525 respondents was conducted in Jakarta to by mailing questionnaire. The result showed that 91% of service providers know about emergency contraception but only 12% of the general practitioners who responded knew about emergency contraception and none of the midwives surveyed knew about it. Those who knew about emergency contraception were not always able to provide contraception services. Only two of 20 obstetricians and gynecologists who knew about emergency contraception actually provided emergency IUD insertions for four clients, and nine obstetricians and gynecologist provided emergency birth control pills of 9 GPs who knew about determine the health the provider’s knowledge about emergency contraception the emergency contraception only 3 gave birth control pills to their clients2°.

In a study on knowledge and attitude about emergency contraception among health workers in Ho Chin Minh City in Vietnam, many providers were familiar well at least one emergency contraceptive regimen few bad accurate, detailed information that extended to knowledge about side effects and indications. In general, providers reportedly over estimated the incidence and severity of side effects of emergency contraceptives, including endometrial carcinoma and chloasma in the often-long lists of emergency contraceptive perils they generated in the discussion groups21.

In New South West Australia 76 urban general practitioners (GPs) and 84 rural GPs completed a questionnaire designed to determine their knowledge, attitude, and prescribing practices concerning emergency contraception by a study carried out by Weisberg, found that rural general practitioners were more likely to know about emergency contraception than urban general practitioners (95 percent vs. 78 percent). Yet, urban general practitioner were more likely than rural general practitioners to receive many requests for emergency contraception and to prescribe it often. Female general practitioners not only were more likely than male general practitioners to know about emergency contraception but also to prescribe it. Fifty eight percent of urban general practitioners and 52 percent of rural general practitioners prescribed the Yuzpe regimen (100 mcg ethiny l estradiol + 500 mcg Levonorgestrerol within 72 hours of unprotected intercourse and repeated 12 hours later). Sixteen percent of both groups always included emergency contraception in discussions about contraceptive options. Eighteen percent only provided this information on request. Sixty percent of all general practitioners would provide information about emergency contraception as a back up to barrier methods.

A survey was conducted in Britain by Crosier among 1354 women aged 16-49 years to assess the levels of knowledge, awareness, and use of emergency contraception. The author found that there was very little spontaneous awareness, the women of the term “emergency contraception.” Less than 25 percent were able to say accurately how long emergency contraceptive pills could be used following unprotected sex contraceptive failure, Forty percent of those women aware of emergency contraception reported having first heard of it from leaflets, books, or magazine articles. Only 14 percent had heard or it from a doctor or other health professional, while 12 percent of respondents reported having used emergency contraception at some time.

In most parts of the world women and even health care providers worldwide do not know that contraception following intercourse is feasible or readily available: few products are specifically marketed for emergency contraceptive use, and service providers are often reluctant to provide emergency methods. Many family planning providers do not offer emergency contraception. Numerous providers do not have adequate knowledge of emergency contraception.

A study carried out by Galvao et. al, among the nationally representative, randomly selected sample of 579 Brazilian obstetrician and gynecologist responded to a 1997 mail in survey on emergency contraception. The data yield information on these providers knowledge about, attitudes towards and practice regarding emergency contraception. The result showed that nearly all respondents (98%) had heard of emergency contraception but many lacked specific knowledge about the method. Some 30% incorrectly believed that emergency contraception acts as an abortifacient and 14% erroneously believed that it, was illegal. However 496.10 of physicians who thought that the method induces abortion and 46% of those who thought that emergency contraception was itself illegal have provided it to elements. Most surprisingly, while 61 % of respondents report having provided emergency contraception, only 15 of -these physicians could correctly list the brand name of a pill they prescribed, the dosage and regimen, and the timing of the first dose.

Burton et al in Tower Hamlets Health Authority London in September 1988 surveyed 88 abortion clients regarding their knowledge of postcoital contraception. It was found that sixty five percent had heard of the “morning after pill”, but among them only 19 percent knew of the 72-hour time Limit. Nine percent thought the time limit was earlier. Examples of confusion over the popular name included: Two women thought it was a pill to- be taken “the morning after” one woman said it was taken every morning; another thought it was for morning sickness; three women believed it was to be used only in case of rape, but not for “ordinary women” and one thought it was illegal. Four women stated that they had thought of using it, but did not know the time limit Eighty one percent said that they would have used postcoital contraception if they had known about it. The study strongly suggested that a public information campaign for clients, general practitioners, medical students, nurses and teachers be set up, and that the name of postcoital -contraception be changed to “emergency contraception.

A study in Europe found that insertion of IUD 5-7 days after the sexual exposure

has been found to be 99 percent effective in preventing pregnancy.

Gross man et al carried out a study. In 1993, with 294 US health care providers designed to determine how frequently they prescribe emergency contraception. These practitioners included obstetrician Gynecologists (OB-GYNs), family practitioners, nurse practitioners, physician’ assistants, nurse midwives, and emergency physicians. This group prescribed emergency hormonal contraception a total of 1009 times in the last 12 months for a mean of 3.4 prescriptions I professional. Thirty one percent of all such prescriptions were for rape victims. More than 66 percent of prescriptions for rape victims were written by emergency physicians. OB-GYNs were the most likely group to have ever prescribed hormonal emergency contraception and to have prescribed it within the last 12 months while family practitioners were the least likely group to do both. Only 8 practitioners inserted an IUD for emergency contraception (15 insertions). Around 90 percent never or rarely discussed emergency contraception with their patients. Just 10 percent had literature on emergency contraception available. About 66 percent of those who had no literature were interested in having this literature available for patients.

Four sets of recommendations were proposed on Methods, Policies and Regulations, IEC / Advocacy, Service Delivery; (I) Methods of emergency contraception should be effective, safe, convenient to use and easily accessible. Ethinyl estradiol-norgestcrl combination oral contraceptives and the copper intrauterine device (IUD) Best meet these requirements. However, experts recommended additional research to develop new methods. Anti-progestegens appear very promising for emergency use. (2) Intergovernmental agencies, governments, and non-governmental organization (NGOs) should ensure that emergency contraceptives are included in all family planning programs and an all national essential drug lists. Drug regulatory authorities should require explicit description of emergency use in the labeling of ethinyI-estradiol-norgestreI oral contraceptives and for the copper IUD. (3) Activities should be developed among women’s group’s professional associations, health advocates, policy makers, NGOs, donors, and community leaders. lEC strategies should consider groups such as adolescents. (4) Emergency contraception should be made available to all women who seek it, provided no contraindications are present. In order to prevent pregnancy following acts of sexual violence and coercion, emergency contraception should also be available from sexually transmitted disease clinics rape crisis canter’s police stations and hospitals.

The April 1995 Bellagio Conference on Emergency Contraception was sponsored by South to South Cooperation in Reproductive Health, Family Health International, the International Planned Parenthood Federation, Population Council, and the World Health- Organization with the support of the Rockefeller Foundation. Twenty-four experts who met at the conference argued that millions of unwanted pregnancies could be averted if emergency contraception were widely available.

During the 20 years of ECP use, no deaths, serious medical complications, fetal malformations, or congenital defects have been reported. The most common side effects of ECPs were nausea and vomiting.

Ngoc. N. T. H. et. al conducted a service of focus group discussions and in depth interviews to explore providers’ knowledge and attitude about emergency contraception’s, including the Yuzpe regimen, the levo-norgestrel emergency contraception regimen, and the post coital insertion of LUDS. Ten focus groups, involving a total of 99 health providers, were held in health facilities affiliated with the Hung Vuong Hospitals Maternal and Child Health! Family Planning network in HO Chi Minh City. Additionally, an in depth interview was conducted with one-individual from all but one discussion group for a total of nine in-depth interviews. Six were held with medical doctors and three with mid wives. The guide covered two main areas, knowledge and attitude of emergency contraceptives in Vietnam. The knowledge section gathered information about appropriate use, side effects and contra indications of emergency contraceptives. The attitudes sections asked about circumstances for the availability and distribution of emergency contraceptives. The result showed that the respondents were typically not familiars with the term “emergency contraception” although many providers knew the concept and some providers could cite examples of emergency’ contraceptive regimens. With the exception of one rural side, when none of the participants had heard of, or used any emergency contraceptives methods, participants in all ‘of the groups had heard of ECP and used earlier.

Gy. Bartfai carried out a questionnaire survey which revealed a significant improvement in the knowledge of emergency contraception over a 12 year period from 12% (1984) to 73% (1996) among women attending for lamination of pregnancy in Dundee, UK, while the use of condom had increased from 32% to 60%, the number of conception due to condom failure had also risen from 8% to 26%. Despite the recognized condom failure, 17% of the cases had been advised of the possibility of pregnancy. A survey among women requesting abortion in Norway in a 2 year period revealed that, despite the fact that EC was known by 93% of the surveyed population, only 42.6% of them had used reliable contraception. Worry about side effects was the most common reason for notusing contraceptives, and among women who considered using it.

According to Anna Graham study assessing the effectiveness of teacher led intervention to improve teenager’s knowledge about emergency contraception in state secondary schools South west England, the proportion of pupils knowing the correct time limits for both types of emergency contraception was 0 significantly higher in the intervention group than in the control group. At six-month follow up the proportion of the boys was 15.9% higher (at 95% confidence interval 6.5% to 25.3%) and among girls 20.4% (at 95% confidence interval 10.4% to 30.4%).

Muja Esther carried out a baseline assessment of hormonal emergency contraception Kenya in September 1996 in under to measure general awareness of the method, ascertain its acceptability, identify potential users and locate possible channels of distribution. The baseline study consisted of structured interviews with five key policy makers, 68 in depths interviews with randomly selected health came providers (physicians nurses and clinical officers) working with the public and prevail sector of Nairobi and 4 focus group discussions with students at two of the public universities. The result showed that policy makers were uniformly positive about the introduction of emergency contraception in Kenya and found the method suitable for a woman, although they were worried about other concern. Nearly 35 percent of all providers interviewed, had heard of ECP, with no difference in familiarity-by the sex of the providers however, fewer than 5 percent of than currently offer EC to women presenting after unprotected intercourse knowledge of EC was extremely & care among the women sampled with only 11 percent of than having heard of EC and 61 percent stating that there is nothing women can do to avoid pregnancy following unprotected intercourse. Knowledge prior to the focus groups ranged from nil to entirely accurate and detailed information, particularly as an alternative to retaining a pregnancy or having an abortion.

The Directorate of Family Planning in collaboration with the Population Councils Frontiers in Reproductive Health Project, Pathfinder International and John Snow Inc (JSI) was conducting a feasibility study to develop, test and document operational details for introducing emergency contraception as a back-up support for existing family planning methods. More specifically, the study intends to determine the acceptability and -appropriate use of ECP among Bangladeshi women and to identify most appropriate service model to make ECP accessible between three study groups. A total of 53 focus group discussions (FGDs) (17 male groups and 36 female groups) and 94 in-depth interviews (32 men and 62 women) were conducted with currently married men and women. A total of 428 persons (308 women and 120 men) participated in the FGDs. with 428 persons. The analysis of the qualitative data revealed that people do not have any knowledge of emergency contraception. And substantial number of women practice harmful traditional methods to protect themselves from unwanted pregnancies. Total 293 services providers were individually interviewed to asses their knowledge and perception use of OCP as EC. The workers were aware that unwanted pregnancies are common. The main reasons for these unwanted pregnancies identified by the providers include non-use of family planning methods(46%) missing pills (87%) , or due date of injection (31 %), condom failure (74%,) unexpected visited by husbands (11%) and miscalculation of safe period(12). Out of 293 workers interviewed, only 64 (22%) were vaguely aware that Sushi (OCP) could be used as an EC. Only four of them were aware of the correct dose, number of pills in each dose, interval between the two doses and the time limit within which ECP must be taken. None mentioned any other brand of pills that could be used as ECP.

In a study Suknmg.K, found that some women in Thailand are using emergency

contraception as a regular birth control pill Frequent use decreases the effectiveness of EC, putting a women a greater risk of becoming pregnant. Researchers are also finding that men, who find out about EC through articles and advertisement in men’s magazines, are the most frequent buyers of EC and are encouraging their partner to use it on regular basis. This reveals that current information on EC is rather limited and many women do not take the recommended dose. EC was first sold over the counter in Thailand about 15 years ago and became instantly popular31.

RJ. Cook, Dick found that In South Africa, a significant proportion of women lack knowledge about access to EC within 72 hours of intercourse.The South African

medical councils allow non-prescription (over the counter) access to Yuzpemet drugs and the French EC drug norIevo38.

A telephone survey was carried out in US among teenagers (age 12- 18 years) by Delbanco. SF. Among the 1510 questioned, only 423(28%) had heard of ECP and only 9% knew that EC pills are effective within 72 hours after unprotected sex. After being informed about EC, 67% of the teenage girl said that they would be interested in the use of EC pills, if needed39.

Drife et al found that about 50 percent of all pregnancies in the UK are unplanned. More than 170,000 pregnancies/year are terminated. About 25 percent of 25 year olds have had an abortion. Contraceptive failure is responsible for almost 50 percent of unwanted pregnancies. About 70 percent of unwanted pregnancies can be predicted because women know that they are at risk after unplanned intercourse or an accident with a condom. Emergency contraception would -prevent pregnancy in 98 percent of these cases. Reasons for non-use include denial of pregnancy risk, not knowing where to get emergency contraception,, and physicians’ control of access to it. Other obstacles are. it is embarrassing to explain to a receptionist why an emergency visit with the physician is needed and family planning clinics do not provide services seven days a week. Women may receive emergency contraception in emergency rooms, but staffs are not best equipped to counsel about sexual behavior3°.

ECP and side effects: ,

In a study among Brazilian obstetrician and gynecologist, in 1997, about one-third (30%) of the health care providers incorrectly believed that emergency contraception acts as an abortifacient and 14% erroneously believed that it was illegal. However, about half (49%) of physicians thought that the method induces abortion and 46% of those who thought that emergency contraception was itself illegal have provided it to elements26.Webb AMC et. al carried out a study and found that women using ECP frequently reported nausea and vomiting 50% and 25% respectively39.

Socio-demographic characteristics and ECP

According to Arowojolu among the 166 ECP users, the mean (SD) age was found to be 21.6 (33) years with highest proportion of were within age 26-30 years. Mostly the students, nurses and midwives were practicing ECP. Regarding religion, the respondents were Protestants (9.6%) and Muslim (19.3%)

ECP and source of information: –

Among those providers who knew about emergency contraception, sources of the information on ECP tend to be consistent. Some providers reported that they learned about emergency contraception through a seminar. Other providers traced their knowledge to medical school. Although many providers were familiar well at least one emergency contraceptive regimen, few had accurate, detailed information that extended to knowledge about side effects and indications. In general, providers reportedly over estimated the incidence and severity of side effects of emergency contraceptives, including eudiometrical carcinoma and cancer of genital tract in the often-long lists of emergency contraceptive perils they generated in the discussion groups.

In the study of the nationally representative randomly selected Brazilian obstetrician and gynecologist in 1997, the data yield information on these providers knowledge about, altitudes toward and practice regarding emergency contraception. The result showed that though nearly all respondents (98%) had heard of emergency contraception but many-lacked source of infonnation.

The International Planned Parenthood federation surveyed the access to EC world wide, in 1994. It is established that the availability of EC differs widely: In Australia, New Zealand, Hong Kong and most countries Europe, this method is offered. In Africa EC is available in only one third of countries and there is no access to this method in Arab countries.

In one controlled trial earned out by Briad D found that more than 1,000 subjects in Scotland. women given a hormonal emergency contraceptive method to keep at home for self -administration were compared with a control group of women who were simply educated about EC and how to obtain it, women who had the method at home were more likely to use it than were those in control group and not likely to use more than once42.

The emergency contraception website -updated monthly website providers up-to -date information on emergency contraception including dosages~for all the different pills43.

Anna Graham et al. carried out a study to asses the effectiveness of a teacher led intervention to improve teenagers knowledge about emergency contraception in ,state secondary schools in Avon, south west England. The study was designed by cluster randomized control trial among 1974 boys and 1820 girls in year 10 (14-15 years old). Questionnaires distributed to pupils at baseline and six months after the intervention assessed their knowledge of the correct time limits for hormonal emergency contraception and for use of the intrauterine device as emergency contraception, the proportion of pupils who had used emergency contraception and the pupils’ intention to use emergency contraception in’ the future. The proportion of pupils knowing the correct time limits for both types of emergency contraception was significantly higher in the intervention group than in the control group at six month follow up. The number of pupils needed to be taught for one more pupil to know the correct time limits was six for boys and five for girls. The intervention and control groups did not differ in the proportion of pupils who were not virgins, in the proportion intending to use emergency contraception in the future35.

Methods and Materials —

The study was conducted among the 96 respondents of a selected hospital in Dhaka Medical College Hospital, Dhaka.

Study design:

It was a cross sectional type of study carried out to determine the level of knowledge among the Married eligible couple.

Study place

The study has been conducted among the Married eligible couple who attended in outdoor of Dhaka Medical College Hospital Dhaka. The institute is situated in Dhaka, and is about 5 km. from zero point and constructed over 3 acres of land. It is a four storied building having 173 beds and several outdoors. Every morning, lots of patients visited this place for several purposes.

The place was selected purposively as it was situated nearby and had easy access. It was possible to conduct the study in that organization as lots of eligible women of reproductive age used to visit here.

Study population: –

Total eligible married women – who used to visit this study place for different occasions. Their socio-economical and demographic characteristics differed from each other. All visitors constituted the study population and each of the visitors was a study unit.

Inclusion criteria:

Eligible married women who visited to the outdoor of Dhaka Medical College Hospital,Dhaka.

Period of study –

The study-was conducted over a period of 16 weeks extending from the first week of March to the last week of January 2012. Data was collected between September to February.

Sampling technique and sample size

After having the kind permission from the authority, the researcher did purposively sampling to collect the total number of sample size of 96 which was determined by using the following formula,

z2pq

n=———–

d2

(Where

n = the desired sample size.

z = the standard normal deviate usually set at 1.96 which correspondents to the 95% confidence level. –

p = No reasonable estimation of prevalence of Repetitive strain injury among the target population and it was considered as 50% (as prevalence was not known).

=50.

Q = 1-p

=100—50 =50.

d = degree of precision and in this study it was 10%) ~

Z2pq (1.96)2x0.5×0.5

n=——————-= ———————–=96.

d2 (.10)2

Data collection Instruments

According to the objectives of the study, a structured interview schedule was developed for collection of required information. The interview schedule was pretested and necessary alteration and modification were made which contains a) the particulars of the respondents, b) information -regarding knowledge of ECPs.

Method of data collection

Data were collected from the respondents who visited for different reason to the study place and had fulfilled the inclusion criteria. A face-to-face interview was carried, out with the help of an interview schedule.

Data processing, analysis and interpretation

After compilation of data, the obtained data were checked, verified, edited and coded. The data were entered into a personal computer using the program SPSS program. Entered data were cleaned, edited and appropriate statistical tests were done depending on the distribution of data.

Results and Findings

Results and Findings

To find out the level of knowledge on emergency contraceptive pill, this cross sectional study was carried out at Dhaka Medical College Hospital Dhaka among the 96 eligible women. This study also tried to find out the knowledge about correct use of ECPs according to their differentials, the financial involvement as well as source of information for getting ECPs.

Socio-demographic characteristics

Age of the respondents

It was seen that the mean age of the respondents was 28.83 years with a standard deviation of 6.27 years and the range between 18-42 years and highest proportion of the age (34.4%) was in the above 30 years age group and the next groups were in the 21-25 years group (28.1%) and 26-30 yrs group (27.1%).

Table-1 : Distribution of the respondents by Age group

Characteristics Frequency Percentage (%)

Age group (years)

Up to 20 yrs 10 10.4

2 1-25 yrs 27 28.1

26-30 yrs 26 27.1

Above 30 yrs 33 34.4

Total 96 100%

Mean 28.83 yrs

SD 6.27 yrs

Religion of the respondents

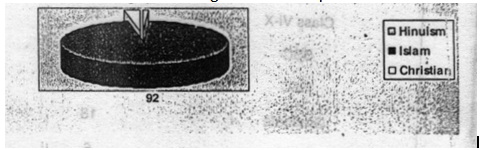

Majority of the respondents (95.9%) was belonged to the religion of Islam and the few of them here Christian (3.1%) and Hindu (1.0%).

Graph-1: Distribution of the respondents by Religion

Religion of the respondents

Educational status of the respondents

Among the 96 respondents, majority of them (90.6%) had formal education where graduate (18.8%), class Vl-X (19.8%), SSC pass (16.7%), HSC pass and Class IV (14.6% in each group) and other (6.3%). The illiterate personnel were only nine in count. (9.4%).

Table-2: Distribution of the respondents by Educational qualification

Characteristics Frequency Percentage

(%)

Educational qualification

Illiterate 9 9.4

Class I-V 14 14.6

Class Vi-X 19 19.8

SSC 16 16.7

HSC 14 14.6

Graduate 18 18.8

Others 6 6.3

Total 96 100%

Educational status of the husbands

Almost similar scenario was observed in the educational level of husband where formal education had the maximum majority [graduate (25.0%), Class I-V and Class Vl-X (15.6% in each group), HSC pass (11.5%), SSC pass (7.3%) and others group like madras education and non formal education (13.5%)]. The illiterate person was just about 12%.

Table-3: Distribution of the respondents by Educational qualification of

Husbands

Characteristics Frequency Percentage (%)

Educational qualification of husbands

Illiterate 11 11.5

Class I-V 15 15.6

Class Vi-X 15 15.6

SSC 7 7.3

HSC 11 11.5

Graduate 24 25.0

Others 13 13.5

Total 96 100%

Information regarding reproductive life

Marriage life

About 43% respondents had duration of marriage life of 5 to 10 years. The next highest one was 10 to 40 years married life (39.6%). About 17% had 2-5 years of married life.

Table-4: Distribution of the respondents by duration of marriage life

Characteristics Frequency Percentage

(%)

Respondents’ duration of marriage life

Just married 1 1.0

2-5 yrs 16 16.7

5.1-l0 yrs 41 42.7

10.1-4o yrs 38 39.6

Live with husband

Maximum respondents (93.8°i) lived with their husband at present where as the rest group was either in husband lived elsewhere in the country (5.2%) or in the country (5.2%) or in abroad (1.0%).

Table-5: Distribution of the respondents by live with husband –

Characteristics Frequency Percentage (%)

Live with husband

Live with husband 90 93.8

Husband lives in abroad 1 1.0

Husband lives in elsewhere in the 5 5.2

country

Number of child

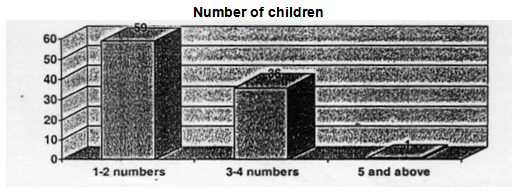

Maximum respondents had either 1-2 number of children (61.4%) or 3-4 numbers of children (37.5%). Only one case was there who had five children (1.0%).

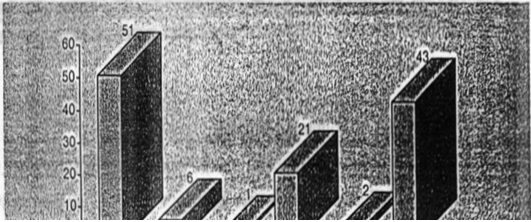

Graph-2: Distribution of the respondents by number of children

Number of children

Presence of family planning methods I

Use of Family planning

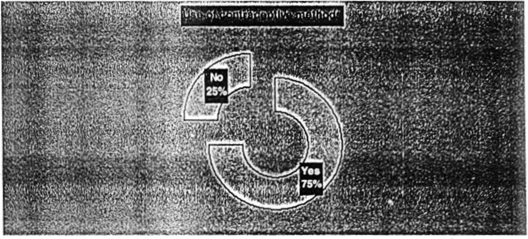

Among the 96 respondents, about seventy five percent of the respondents had a history of using contraceptive methods.

Graph-3: Distribution of the respondents by contraceptive use

Type of family planning methods used

Different type of contraceptives was used by seventy two respondents. Among more than half, 51(70.8%) of the respondents were using oral pills. Next popular contraceptive found to be practiced was condom (59.7%). Injection, used by twenty one respondents, constituting 29.2% percent of total contraceptive users’ respondents. Least practiced contraceptives were copper 1 (8.3%), traditional way that was safe period (2.8%) and Norplant (1 .4%)-(figure-)

Graph 4: Distribution of the respondents by used family planning methods

Occupational Characteristics and Income status

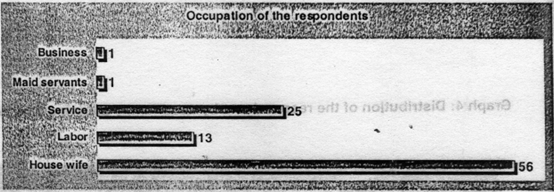

Occupation of the respondents

The majority of the respondents (58.3%) were house wife and the next occupations were service (26.0%) and day labor (13.5%). A small portion of the respondents were doing some sorts of business and work as maid servant.

Graph-5: Distribution of the respondents by occupation of the respondents

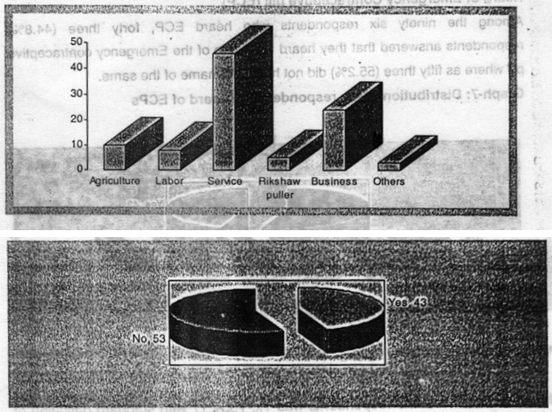

Occupation of the respondents’ husband

The maximum respondents’ husband was engaged either in service (47.9%) or business (25.0%). The next groups were agriculture (10.4%), day labor (8.4%) and rickshaw puller (5.2%) and other groups(3.1% in total) included carpenters, fisherman, and broker.

Graph-6: Distribution of the respondents by occupation of the respondents’ husband

The mean income of the respondents was Tk. 7354.17 with standard deviation of tk. 5123.71 and range was 1k. 400 to 1k. 25000. The majority of the respondents were belonged to either in up to 1k. 3000 (39.6%) or in more than Tk. 6000 groups (37.5%). The other group was in Tk. 3001-6000 (22.6%).

Table-6: Distribution of the respondents by family income

Characteristics Frequency Percentage (%)

Income of the respondents ..

Upto Tk. 3000 36 37.5

tk. 3001-6000 22 •, 22.9

>Tk. 6000 38 39.6

Knowledge about emergency contraceptive pill (ECP)

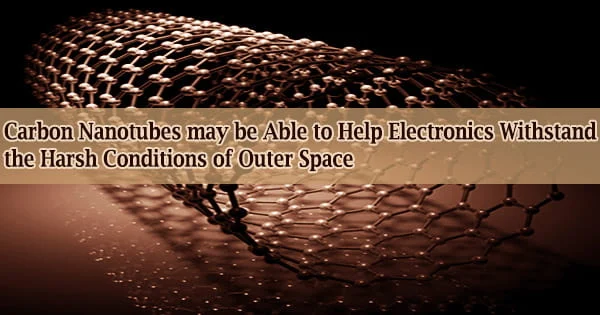

Heard of Emergency Contraceptive pill (ECP)

Among the ninety six respondents who heard ECP, forty three (44.8%) respondents answered that they heard the name of the Emergency contraceptive pill where as fifty three (55.2%) did not heard the name of the same.

Among the respondents who heard the name of ECPs, nineteen (44.2%) could mention correctly the brand of Pastinor-2 that called as ECP. More over, it was found that about eight respondents (18.6%) could not recollect any of the name of ECPs and 37.2% answered wrongly.

Table-7: Distribution of the respondents by knowledge about the name of the ECPs

Characteristics Frequency Percentage

Name of ECPs

Wrong answer

Shukhi 9 20.9

C-5 4 9.3

Maya 3 70

Correct answer .

Pastinor-2 1~9 44.2

Other

Do not know 8 18.6

Total 43 100%

Knowledge about the use of ECPs

Among the positive answer regarding of knowledge of use of ECPs, twenty seven respondents replied that ECPs was used to protect unwanted pregnancy in emergency. Seven percent respondents found it as a regular birth control purpose. But thirteen respondents (30.2%) could not mention any reasons of using ECPs.

Table-8: Distribution of the respondents by knowledge on reason of use of ECPs

Characteristics Frequency Percentage (%)

The reason of taking ECP

Emergency protection against 27 62.8

unwanted pregnancy

Regular birth control purpose 3 7.0

Do not know 13 30.2

Pill number in ECP method

2 tab. 29 67.4

4tab 7 16.3

30 tab 4 9.3

Do not know 3 7.0

Table-9: Distribution of t he !?sPondents by knowledge about the number of pill in ECPs

Characteristics Frequency Percentage (%)

Pill number in ECP method

2 tab. 29 67.4

4tab 7 16.3

30 tab 4 9.3

Do not know 3 7.0

Total 43 100%

Knowledge about the Number of total pills in ECP

Knowledge about dose of the ECPs

Among the 43 respondents, the majority of the respondents (60.5%) had knowledge that two doses present in the ECPs. Further more; about 9.3% of the respondents had no idea about the doses in ECPs.

Table-9.b: Distribution of the respondents by knowledge abut the dose of ECPs

Characteristics – Frequency Percentage (%)

Dose of ECP

Wrong answer

8 dose 9 20.9

4 dose 4 9.3

Correct answer

2 dose 26 60.5

Other

Do not know 4 9.3

Total 43 100%

Knowledge about the number of pill in each dose

Regarding the number of pill in each dose, about 51 percent thought that there was single tablet in each dose, where as twelve respondents (27.9%) found 2 tablets and 3 respondents replied that there was 4 tablets in each dose of ECPs. Again, about 14% had no knowledge regarding the pill in each dose.

Gap between two doses

Among the 43 aware persons, 30 (69.8%) respondents replied that the gap between the two doses was 12 hours. On the other hand, five (11.6%) and three respondents (7.0%) mentioned that the gap was 8 hours and 10 hours respectively. Again, the percent of having no knowledge regarding the gap was 11.6%.

Table-11: Distribution of the respondents by knowledge about the gap between two doses of ECPs

Characteristics Frequency Percentage (%)

Gap between two doses

Wrong answer

8hrs 5 11.6

l0hrs 3 7.0

Correct answer

l2hrs 30 69.8

Other

Donot know 5 11.6

Total 43 100%

Knowledge about the time of first dose

About 30 respondents (69.8%) answered correctly that time of having first dose was within 72 hours. The other answers were within 12 hours (9.3%) and within 24 hours (7.0%) which was wrong. Again, the percent of respondents who had no knowledge regarding time of first dose was 14.0%.

Table-12: Distribution of the respondents by knowledge of time of first dose of ECPs

Characteristics Frequency Percentage (%)

Time of first dose

Within 12 hrs 4 9.3

Within 24 hrs 3 7.0

Within 72 hrs 30 69.8

Do not know 6 14.0

Knowledge about safeties of ECPs

About 36 respondents (83.7%) found that ECPs was safe and 7 respondents (16.3%) did not think that ECPs was safe.

Knowledge of indication of ECPs

Among the respondents, about 61% percent (60.5%) replied that the indication of ECPs use was unsafe sex, rupture of condom and forget of taking contraceptive pill for three consecutive days. Besides, 8 respondents (18.6%) did answer that forget of having pill for three consecutive days, 6 respondents (14.0%) found the indication was due to unsafe sex and two respondents (4.7%) replied that it was due to rupture of condom. one respondent had no knowledge about the indication of ECPs.

Table-13: Distribution of the respondents by knowledge of indication of ECPs

Characteristics Frequency Percentage (%)

Knowledge of indication of ECP use (n=43)

Forget to take pill for consecutive 8 18.6

three days

Unsafe sex 6 14.0

Rupture of condom 2 4.7

Correct the above three answer 26 60.5

Do not know 1 2.3

Knowledge of Place of availability of ECP

Among the respondents who heard about ECPs, 28 respondents (65.1%) replied that the place of availability of ECPs was health center. Field health workers (39.5%) and pharmacy (27.9%) and other were the other places where ECPs was the place of available of ECPs according to the respondents.

Table-14: Distribution of the respondents by knowledge of Place of availability of ECP

Characteristics – Frequency Percentage (%)

Place of availability of ECP (n=43)

Health centre 28 65.1

Pharmacy 12 27.9

Field health workers 17 39.5

Others 7 16.3

Knowledge of Source of information about ECP

Service providers (79.1%) were the single most source of information about the ECPs. The other sources were friend (7.0%), relatives and neighbor and husband were in equal percentage.

Table-15: Distribution of the respondents by knowledge of Source of information about ECP

Characteristics Frequency Percentage (%)

Source of information about ECP

(n=43)

Service providers 34 79.1

Relatives 2 4.7

Neighbors 2 4.7

Friend 3 7.0

Husband 2 4.7

Knowledge about side effect of ECP

The respondents experienced different types of side effects. Majority (72.9%) knew of nausea and least knew about pain in breast.

Table-16: Distribution of the respondents by knowledge about side effect of ECP by the respondents

Characteristics Frequency Percentage (%)

Knowledge about side effect of ECP

(n=43)

Nausea 31 72.9

Vomiting 25 58.1

Vertigo 10 23.3

Pain in breast 3 6.9

Knowledge of the respondents regarding repeat of ECPs within 1 hour of vomiting:

About more than fifty percent (58.1%) of the respondents who heard about the ECPs thought that ECPs could be repeated within one hour of vomiting if occurred. On the other hand, 7 respondents did not think that ECPs could be used within one of vomiting. Besides, 11 respondents did not anything about the repeating of ECPs within one hour of vomiting.

Knowledge on repeating of ECPs within one hour of voming

Knowledge about breastfeeding with ECP use

About seventy two respondents (72.1%) thought that ECPs could safely use in the period of breast feeding, but 5 respondents thought that ECPs could not use in the breast feeding phase. Sixteen percent did not know.

Table-17: Distribution of the respondents by Knowledge about breastfeeding with ECP use

Characteristics Frequency Percentage

Knowledge about breastfeeding with ECP use

(n=43)

Yes 31 72.1

No 5 11.6

Do not know 7 16.3

Knowledge about starting time of birth control pill after ECP use-

About twenty six respondents (60.5%) replied that the birth control pill could be used immediately after ECPs use and thirteen respondents (30.2%)~ found that the regular birth control pill had to use from the first date of next menstruation. One person (2.3%) found no need of use of birth control pill. But three respondents (7.0%) were found to have no idea about the starting time.

Table-18: Distribution of the respondents by knowledge about starting time of birth control pill after ECP use

Characteristics Frequency Percentage (%)

Starting time of regular Birth control method after ECP

(n=43)

No need of use 1 2.3

Immediately 26 60.5

First date next menstruation 13 30.2

Do not know 3 7.0

Knowledge regarding time of ECPs use in unsafe sex

Maximum respondents (93.0%) had idea about the time of use of ECPs in unsafe sex that was after having unsafe sex which was correct. Only one respondent (2.3%) replied that the time was before having sex that was incorrect. About 4.7% of the respondents had no idea about the time of having ECPs in unsafe sex.

Table-19:Distribution of the respondents by Knowledge regarding time of ECPs use in unsafe sex

Characteristics Frequency Percentage (%)

Time of ECP use in Unsafe sex

(n=43)

Before the sex 1 2.3

After having sex 40 93.0

Do not know 2 4.7

Practice of ECP

Among the 43 aware person, only fourteen of the respondents (32.6%) had a history of practicing ECPs in their reproductive life and twenty nine respondents (67.4%) did not ever practice the ECPs.

Practice of ECPs

Reason of ECPs use

Among the respondents who practiced the ECPs, five respondents (62.5%) ever practiced the ECPs due to refusal of husband to take any method. Other three respondents did practice due to intolerability of pill, due to medical causes like high blood pressure and Diabetes and other disease, and due to other cause (one in each reason)

Table-20: Distribution of the respondents by reason of ECPs use

Characteristics Frequency Percentage (%)

Reason of ECP use (n=8)

Refusal of husband to take any method 5 62.5

Intolerability of pill 1 12.5

Presence of High blood pressure, 1 12.5

diabetes and other disease

Others 1 12.5

Relationship between respondent’s socio-demographic characteristics and awareness about ECPs

Age of the respondents:

Group t test was applied to see whether there was any difference of age between two groups and was found that there was statistically difference in the mean of -positive aware group than the mean of not aware group (p<.01).

Educational qualification of the respondents:

It was seen in the Chi-square test that thee was no significant difference between the different type of educational status of respondents and who heard about ECPs (p>0.05).

Educational qualification of the respondents’ husband:

Chi-square test revealed no significant difference in between the different type of educational status of the husband and awareness of ECPs(p>.05).

Occupational status of respondents

It was seen in Chi-square test that those who was in service had statistically better aware than house wife and other group of the respondents (p<.05).

Occupational status of the husband

Similar scenario was observed in Chi-square test when applied to test the relationship between the educational status and awareness of ECPs that was service group had significantly better aware than the other groups (p<.05).

Income status of the respondents:

The mean of better income group had statistically more aware about ECPs than the mean of lower income group when group t test was applied (p<0.05).

Marriage life

It was found that there was a significant relation between the means of duration of marital age of the different types of aware groups which was observed in student t test (p<.01)

Discussion:

The female respondents of the slum area had a wide range of mentality as well as characteristics that might influence their knowledge on emergency contraceptive pill (ECPs). The researcher reported the results of this cross sectional study that conducted among the eligible married female respondents attending in a selected hospital of Dhaka city.

Although the limitations included potential selection bias inherent in cross sectional studies and the depth of knowledge regarding ECPs was not formally assessed. Rather the researcher through this study had relied mainly on questionnaire response which was not standardized.

It was found from the study that the mean age of the respondents was 28.83yrs with standard deviation of 6.27yrs. Age of the respondents ranged from 18’- 42yrs. Finding were supported by the study of Arowjulu40. But the findings were different in the Brazilian study, when the majority was. (47%) within the age group of 11 to 20 yrs26. It might be due to difference socio cultural background.

The mean monthly family income of the responded was fond to be Tk. 7354.17 with SD of ± 5123.17 will be range Tk. 400 to 25000. More than half of the responded (62.2%) has a family income below Tk. 6000. The opposite scenario was seen in the Brazilian study when majority was in the upper income group26. This might be due to area specific findings.

All of the respondent was married, majority were Muslims (95.9%), religion of the respondent was found different in other study, kike Bhutan it all where Pentecostals (49.4%), Catholics (13.3%), Protestants (9.6%) and Muslim

(19.3%)27. This might be due to the common scenario of Bangladesh where Muslim predominant.

Educational status of the both husband and wife was almost same where both of them had formal education maximum can among the respondents, about three-fourth of the respondents (75%) were found to have practice different type of family planning methods. Though they used different types of family planning methods but most commonly methods were found to be oral contractive methods (70.8%) and condom (59.7%)

This findings was supported by the findings of BDH report & the Nigerian study40.

About forty-four respondents heard the name of the ECPs where about 20% of the respondents could able’ to mention the name of Pastlnor-2 as ECPs. This study had the opposite scenario that was seen in the study done by Nahid MukiIk13 when the majority (65.3%) of the respondents known the Pastenor-2 as ECP~. Again it might be due to area specific findings and as ECPs is a comparatively new method.

Among the respondents, about 8% of the respondent did practice the ECPs in any time of their reproductive age. This findings was not support the findings of Netherlands, where it was well practiced among the respondents who knew about ECPs19 but almost similar to the study conducted by Crosier when only 12% used the ECps24.

In the study of Crosier it et. al24, the source of hearing of ECPs was leaflets, books, magazine and articles and from medical professional. On the other hand, medical school was found as the source of knowledge of ECP is Charlotte et. als study. The current study had dissimilarity with the above two studies as service providers was the right most source of knowledge. This might be due to less support was given by mass media in Bangladesh.

Among the respondents who know the name of ECPs about 70% of the respondents could mention correctly, the time of first dose of ECPs and the time interval and about 60% of the respondents did answer correctly the total number of dose of ECPs. These findings do not have similarity with study conducted by Crosier24, Galavo et. al26 and Burton et. all27.

Knowledge regarding safeness of ECP should that among the 43 respondents who hard the ECPs, 36 respondents (83.77%) had thought that ECPs was safe to practice. The findings as similar to findings of a study paper recently presented in population council21. -Regarding side effects of ECP, a study in Brazil26 about one-third (30%) of the health care providers incorrectly believed that emergency contraception acts as an abortificiant and 14% erroneously believed that it was illegal. However, about half (45%) of physicians thought that methods includes abrogation and about half found it to induce nausea & variety13’26’39. These findings were similar to the findings of the current study where nausea (72.9%) was the main feature and least was pain in the breast.

Conclusion:

This study concluded that Emergency Contraceptive Pill (ECP) was relatives a new conception of contraceptive methods among the respondents. The service delivery structures needs to portray mark of health education activities to guide the eligible married women regarding emergency contraceptive pills (ECP5).

The mean age of the respondents was 28.53 ± 6.27 yrs. The majority of the respondents were Muslim in religion (95.9%), having different types of formal education (90.6%). The majorities of the respondents was housewife (58.3%) and mean family income was Tk. 7354.17 ± 5123.71.The duration of marriage life of the respondents was above five years in maximum of the respondents (82.3%) and maximum of the respondents had 1 to 2 children (61.4%).Maximum respondents (75.0%) used different type of family planning methods where oral pill (70.8%). and condom (59.7%) were the choice of contraceptive pill and the rest (44.8%) did hear the name where only 8 respondents did used the products at any time of their reproductive age and cause of maximum cases was referred of husband to take any methods during sex.

Moreover, about 30% respondents did know the cause of ECP use and time interval and limit, dose and safety ness and place of availability of ECPs.

The statistical relationship was found between the aware groups and age (Pl’01), occupation (PL’05), income (Pl’05) duration of marriage life of the respondents , (PL’01) and occupation of husband (PL’05).

So there was a need of counseling as well as involvement of man media in order to improve the awareness and practice of Emergency Contraceptive Pills (ECPs)

Recommendation:

On the basis of the findings of the study, the following recommendations are put forward for consideration of the future researcher and policy makers-

1. The health services structure in BangIadesh should be tailored to provide knowledge regarding emergency contraceptive pill, thus helps to prevent the unwanted pregnancy.

2. Mass media should come forward to focus the importance of emergency contraceptive pills and also notify the available emergency contraceptive pill.

Additional in depth research is needed to determine the level of knowledge on emergency contraceptive pills.

Bibliography:

1. United nations 1994. report of the International Conference on Population and Development, (Cairo, 5-13 September 1994).WCONF~ 171113.).

2. Ellertson C. 1996. History and• Efficacy of Emergency Contracetion, Family Planning Perspective 22(2) L 52-56.

3. Nayar A. 1 997m Emergency Contraceptive : The need for Media Advocacy, Paper presented at workshop or Emergency Contraception December 9-10, 1997, Dhaka, Bangladesh.

4. Glasier A, Ketting. E, Patan V.T., Browne L, Kaur. S, Bilian, X, Graza-Flores, J, Estrada LV., Delano, G, Fooye, G., Ellertson, C. and Armstrong, E. 1996 ~Case studies in Emergency Contraception, from 6 countries: Netherlands, Malaysia, China, Mexico & Nigeria” International FamUy ~‘lanning Perspective. 1996 Jun; 22(2): 52-54. ~‘

5. Emergency contraception: A Responsible DQcision, Emergency Contraception Ensuring Women’s rights to Health. Latin American and Caribbean Women’s Health Network (LACWHN) 2001 p-5.

6. Chowdhury, l.A. Emergency Contraception: “Service providers Concerns and Consideration”. In: Emergency Contraception Workshop Proceedings. Dhaka, Bangladesh’s 1998: p 58-59:

7. Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey 1999-2000: Preliminary report. NIPOR T .Dhaka, Bangladesh.

8. Singh S et at Estimating the level of abortion in the Philippines and Bangladesh. International Family Planning Perspectives. September 1997; 23(3): 100-106.

9. Statistical Pocket Book of Bangladesh 2001 .Dhaka: BBS.

10. Health and population Sector programmed. Programmed implementation plan. Dhaka: Ministry of health and welfare 1998-2003: Government of Bangladesh.

11. Emergency Contraception: A Guide For Service Delivery. WHO / FRHIFPP / 98:

p9-10.

12. Kamal, H., S.F. Begum, ~nd G. M. Kamala. Prospects of Menstrual regulation Services in Bangladesh: Results of an Operations research. Monograph. Dhaka:

Bangladesh Association for Prevention of Septic Abortion (BAPSA). 1993.

13. Chowdhury S, Nahid M, Sharif Ml. Hussain, Namely H. “Knowledge, Attitude and Practices on EC among Health Care Providers and Drug Sellers in Dhaka city.TM In Emergency Contraception Workshop. Dhaka, Bangladesh: Population Council,1998: p 103-1 04.

14. Training of Service Providers On Emergency Contraception: Lessons Learned from an OR study, In: Research Update No 2 March 2002.

15. Use of emergency Contrace~tion pilI~ Could Halve the Induced Abortion Rate in

Shanghai, China.” UNDP / UNFPA / WHO / World Bank Special Programmes of

Research, Training In Human Reproduction. In : Sociai, Science Research Policy

Briefs. 2001, Series 2: 1 from an OR study, In: Research Update No 2 March

2002.

16. Chowdhury S, Nahid ~1, Sharif MI. Hussain, Namely H. “Knowledge, Attitude and Practices on EC among Health Care Providers and Drug Sellers in Dhaka city.TM In Emergency Contraception Workshop. Dhaka, Bangladesh: Population Council, 1998: p 103-1 04.

17. Trussel J. Stewant F, Gust F and Hacher R.A, Emergency Contracption Pills : a simple proposal to reduce unwanted pregnancies. Fam. Plann. Perspective 1992;

24, 269-273.

18. Trussel J. Stewant F, Koiery J. Darroeh JE, Medical can costs saving from adolescent contractive use. Fam. Plann. Perceptive 1997, 29, 248-255.

19. Emergency Contraceptive Pills: Medical aRd Service Delivery Guidelines, Consortium For emergency contraception. Octot~r 2000.

20. Health Providers Knowledge about Emergency contraception In JAKARTA. Indonesia Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1996; 20(2): 88-89.

21. Ngoc NTN, Charlotte E, Yukolsiri S, Ly.T.Loc. Knowledge and Attitude about emergency Contraception among Health Workers in Ho Chin Minh city, Vietnam. Paper presented in the Workshop on Emergency contraception. Dec 9-10, 1997 Dhaka, Bangladesh, Organized by POPULATION COUNCIL, Concerned Women for Family Planning Dhaka Bangladesh.

22. Introducing Emergency Contraception In Bangladesh, Population Councils, Frontiers in Reproductive Health Project, Pathfinder International and John Snow Inc (JSI) March:2001

23. Weisberg.E. “Emergency Contraception: General Practtitioner Knowledge, Attitude and Practices in New South Wales.” Medical Journal of Australia.” 1995; 162(3):

326-330.

24. Crosier A. “Women knowledge and awareness of emergency contraception.” British Journal of Family Planning..1996 JULY; 22(2): 87-~1

25. Family Health International [FHI]; World Health Organization [who]; International Planned Parenthood Federation [IPPF]; Population Council South to South Cooperation in Reproductive Health. Emergency contraception should be available to all women; Research Traingle Park, North CaroIina, FHI, 1995 May

26. Galavo 1, Diaz.J J, Mariah et at. Emergency Cont’raception: Knowledge, Attitude. and Practices Among Brazilian Obstretician-GynaecolOgist.lnternational Family Planning Perspectives. 1999,25(4): 168-80

27. Burton RW. “Knowledge and Use of Postcoital Contraception: A Survey Among Health Professionals in Tower Hamlets, British Journal of General Practitioners

1995; 40(337): 326-30.

28. Kestelman P. When is “Emergency” contraception the right name for postcoital treatment? Planned Pamthood in Europe; 1995 Aug; 24(2): 132

29. Grossman RA. How frequently is emergency contraceptive prescribed? Family Planning Perspectives. 1994 Nov-Dec; 26(6): 270-1.

30. Drife JO. Deregulating emergency contraception. Justified on current information.

BMJ. 1993 Sep 18; 307(6906) : 695-6.

31. Family Health International [FHl~WorId Health Organization (WHO); International Planned Parenthood Federation (IPPF]; Population Council.

32. Pathfinder International and Emergency Contraception Hotline.

33. Charlotte E. Knowledge and attitude about emergencj Contraception among Health Workers in Vietnum. ~Paper presented in the Workshop on Emergency contraception. Dec 9-10, 1997 Dhaka, Bangladesh.

34. Gy Bartfai. Emergency Contraceptive in Clinical Practice: Global Perspectives. International Journal of Gynaecology & Obstetrics 2002; 49-58.

35. Anna Graham, Laurence More, Deborah Sharph, lan Diamond. Improvings Teenagers Knowledge of emergency contraception: A randomised control trial of a teacher led intervention. BMJ Vol 324 18 May 2002. www.bmi.com

36. Muja Esther. Enhancing the use of Emergency Contraception in Kenya. Paper presented in the workshop on Emergency Contraception, Dec 9-10, 1997. Dhaka, Bangladesh.

37. Sukrung K. Morning- after blues: excessive and incorrect use of an oral, contraceptive designed for emergency use ~nly is resulting in ‘unwanted pregnancies and worse. www.banqkokpost.com/en/outlook/l 0iun2002~out5i /lOiune 2002.

38. RJ.Kook, Dick. Yuzpe method drugs and the~ French EC drug Norlevo: International journal of Gynecology and obstetrics. 75 (2001) 185-191.

39. Webb. AMC, Russell, ElsteinM. Comparison of Yuzpe regeimen, Danazol, and Mifepristone, RU-486 in oral post coital contraception. B Med J. 1992; 305: 927- 931.

40. A.D. Arowojolu , A.D. Adekunle. Knowledge and practice of emergency contraception among Nigerian youths: international Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics 66(1999) 31-32.

41. SenanayakeP. Emergency contraception: The International Planned ParenthQod Federations experience. Int. Fam. Plann. Per~p. 1996; 22:69-70.

42. Glasier. A BriadD. The effects of self administering EC. N. ENG. J Med. 1998; 339: 1-4 (level 11-1).

43. www.Not-21 ate.Com