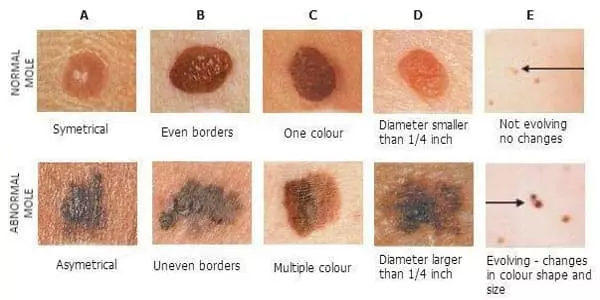

A common mole is skin growth that occurs when pigment cells (melanocytes) cluster together. The average adult has between 10 and 40 common moles. These growths are typically found above the waist in sun-exposed areas. They are rarely discovered on the scalp, breast, or buttocks. Common moles can be present at birth, but they usually appear later in childhood. Most people continue to develop new moles until they are around the age of 40. Common moles tend to fade away in older people.

A common mole rarely develops into melanoma, the most serious form of skin cancer. Although common moles are not cancerous, people with more than 50 common moles are more likely to develop melanoma. Melanoma is a form of skin cancer that starts in the melanocytes. It is potentially dangerous because it has the ability to infiltrate nearby tissues and spread to other parts of the body such as the lung, liver, bone, or brain. The earlier melanoma is detected and removed, the better the chances of successful treatment.

Melanoma researchers published a study that provides a new explanation for why moles develop into melanoma. These findings pave the way for additional research into how to reduce the risk of melanoma, delay its development, and detect it early.

We discovered a new molecular mechanism that explains how moles form, how melanomas form, and why moles occasionally become melanomas. The study found that melanocytes that develop into melanoma are not affected by additional mutations, but rather by environmental signaling, which occurs when cells receive signals from the environment in the skin around them that direct them.

Judson-Torres

Moles and melanomas are both skin tumors that develop from the same melanocyte cell. The difference is that moles are usually harmless, whereas melanomas are cancerous and can be fatal if left untreated. Robert Judson-Torres, PhD, Huntsman Cancer Institute (HCI) researcher and University of Utah (U of U) assistant professor of dermatology and oncological sciences, explains how common moles and melanomas form and why moles can progress to melanoma in a study published in eLife Magazine.

Melanocytes are cells that give the skin color in order to protect it from the sun’s rays. Over 75% of moles have specific changes to the DNA sequence of melanocytes, known as BRAF gene mutations. The same change is found in 50% of melanomas and is common in cancers such as colon and lung. When melanocytes only have the BRAFV600E mutation, the cell stops dividing, resulting in a mole, it was thought. Melanoma develops when melanocytes have other mutations with BRAFV600E and divide uncontrollably. This is known as “oncogene-induced senescence.”

“In recent years, a number of studies have challenged this model,” Judson-Torres says. “These studies have provided excellent data indicating that the oncogene-induced senescence model does not explain mole formation, but what they have all lacked is an alternative explanation, which has remained elusive.”

Melanoma can occur on any skin surface because the majority of melanocytes are found in the skin. It can grow from a common mole or a dysplastic nevus, or it can grow in an area of seemingly normal skin. Melanoma can also form in the eye, the digestive tract, and other parts of the body.

Melanoma in men is frequently found on the head, neck, or back. Melanoma in women is frequently found on the back or in the lower legs. Melanoma is much less likely to develop in people with dark skin than in people with fair skin. When it does appear in people with dark skin, it is frequently found under the fingernails, toenails, palms of the hands, or soles of the feet.

The study team used transcriptomic profiling and digital holographic cytometry on moles and melanomas donated by patients, with assistance from collaborators at HCI and the University of California, San Francisco. Transcriptomic profiling enables researchers to distinguish moles from melanomas at the molecular level. Researchers can use digital holographic cytometry to track changes in human cells.

“We discovered a new molecular mechanism that explains how moles form, how melanomas form, and why moles occasionally become melanomas,” Judson-Torres says. The study found that melanocytes that develop into melanoma are not affected by additional mutations, but rather by environmental signaling, which occurs when cells receive signals from the environment in the skin around them that direct them. Melanocytes express genes in various environments that instruct them to either divide uncontrollably or stop dividing entirely.

“The fact that the origins of melanoma are dependent on environmental signals opens up new avenues for prevention and treatment,” says Judson-Torres. “It also aids in the fight against melanoma by preventing and targeting genetic mutations. We may also be able to fight melanoma by altering the environment.”

These findings lay the groundwork for future research into potential melanoma biomarkers, which will allow doctors to detect cancerous changes in the blood at an earlier stage. The researchers also hope to use this information to better understand potential topical agents for reducing the risk of melanoma, delaying or stopping recurrence, and detecting melanoma early.