A commonly held belief that Native Americans originated in Japan has been debunked by a recent scientific study that claims the genetics and skeleton biology “simply does not match up.”

The findings, which were published in the peer-reviewed journal PaleoAmerica today, are likely to change how we think about Indigenous Americans’ arrival in the Western Hemisphere.

Many archaeologists now assume that Indigenous Americans, or ‘First Peoples,’ moved to the Americas from Japan around 15,000 years ago, based on parallels in stone artifacts. They are assumed to have traveled along the Pacific Ocean’s northern rim, passing via the Bering Land Bridge on their way to the northwest coast of North America.

Within fewer than two thousand years, the First Peoples had spread across the interior of the continent and further south, reaching the southern point of South America.

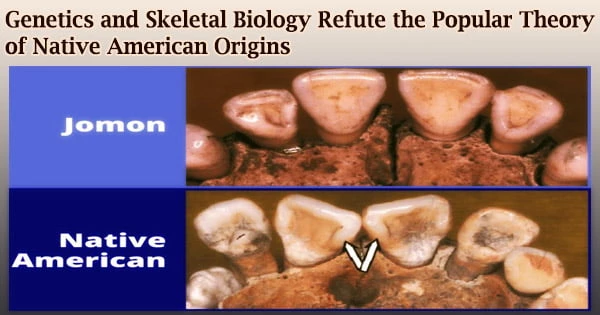

The argument is based on similarities between stone tools manufactured by the ‘Jomon’ people (an early inhabitant of Japan who lived 15,000 years ago) and those discovered in some of the oldest known archaeological sites inhabited by ancient First Peoples.

However, a new study published today in PaleoAmerica, the flagship publication of Texas A&M University’s Center for the Study of the First Americans, shows otherwise.

The study, which was led by one of the world’s leading experts in the study of human teeth and a team of Ice-Age human genetics experts, looked at the biology and genetic coding of dental samples from several continents and focused specifically on the Jomon people.

“We found that the human biology simply doesn’t match up with the archaeological theory,” states lead author Professor Richard Scott, a recognized expert in the study of human teeth, who led a team of multidisciplinary researchers. “We do not dispute the idea that ancient Native Americans arrived via the Northwest Pacific coast only the theory that they originated with the Jomon people in Japan.”

These people (the Jomon), who lived 15,000 years ago in Japan, are an unusual source for Indigenous Americans. There is no evidence of a link between Japan and America in skeletal biology or genetics. Siberia looks to be the most plausible source of the Native American population.

We found that the human biology simply doesn’t match up with the archaeological theory. We do not dispute the idea that ancient Native Americans arrived via the Northwest Pacific coast only the theory that they originated with the Jomon people in Japan.

Richard Scott

Scott, an anthropology professor at the University of Nevada-Reno, has traveled throughout the world for over half a century, accumulating a large amount of material on ancient and modern human teeth. He has written a number of scientific papers and books on the subject.

This study used multivariate statistical tools to analyze a huge sample of teeth from the Americas, Asia, and the Pacific, concluding that a quantitative comparison of the teeth showed no relationship between the Jomon and Native Americans.

In fact, non-Arctic Native Americans were only linked to 7% of the dental samples (recognized as the First Peoples). Furthermore, genetics reveal a similar pattern to that of the teeth, indicating that the Jomon people and Native Americans have little in common.

“This is particularly clear in the distribution of maternal and paternal lineages, which do not overlap between the early Jomon and American populations,” states co-author Professor Dennis O’Rourke, who was joined by fellow human geneticists and expert of the genetics of Indigenous Americans at the University of Kansas, Jennifer Raff.

“Plus, recent studies of ancient DNA from Asia reveal that the two peoples split from a common ancestor at a much earlier time,” adds Professor O’Rourke.

In 2016, O’Rourke and Raff published the first analysis of ancient DNA from Ice-Age human bones in Alaska with their colleague and co-author Justin Tackney.

Specialists in Ice-Age archaeology and ecology are among the other co-authors. Two fresh research on relevant themes were published shortly before the paper was published.

A new genetics study of the modern Japanese population found that it is the result of three distinct migrations into Japan, rather than the two previously thought. It did, however, lend greater credence to the scientists’ conclusions concerning the lack of a biological link between the Jomon and Indigenous Americans.

And, in late September, archaeologists reported in another paper the startling discovery of ancient footprints in New Mexico dating to 23,000 years ago, described as “definitive evidence” of people in North America before the Last Glacial Maximum before expanding glaciers probably cut off access from the Bering Land Bridge to the Western Hemisphere. It remains unclear who made the footprints and how they are related to living Native Americans, but the new paper provides no evidence that the latter are derived from Japan.”

Professor Scott concludes that, “the Incipient Jomon population represents one of the least likely sources for Native American peoples of any of the non-African populations.”

The study’s limitations include the fact that the oldest teeth and ancient DNA samples for the Jomon population are less than 10,000 years old, i.e., they do not predate the early Holocene (when the First Peoples are understood to arrive in America).

“We assume,” the authors explain however, “that they are valid proxies for the Incipient Jomon population or the people who made stemmed points in Japan 16,000-15,000 years ago.”