A fresh close-up view of Pluto in the most recent data from NASA’s New Horizons probe shows a wide, craterless plain that appears to be no older than 100 million years old and may still be being formed by geological processes.

In honor of Clyde Tombaugh, who discovered Pluto at 1930, this frozen area is located north of Pluto’s icy mountains, in the center-left of the heart feature. It is known as the “Tombaugh Regio” (Tombaugh Region).

“This terrain is not easy to explain,” said Jeff Moore, leader of the New Horizons Geology, Geophysics and Imaging Team (GGI) at NASA’s Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, California. “The discovery of vast, craterless, very young plains on Pluto exceeds all pre-flyby expectations.”

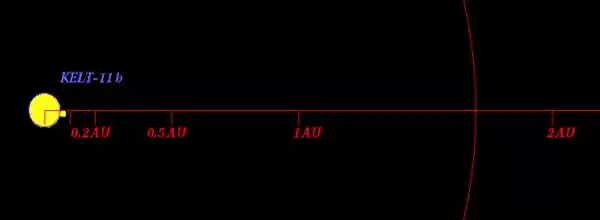

In honor of the planet’s first artificial satellite, Sputnik, this remarkable area of freezing plains that resembles frozen mud cracks on Earth has been given the informal name “Sputnik Planum” (Sputnik Plain). It is around 12 miles (20 kilometers) broad, with a shattered surface of irregularly shaped parts, flanked by what seem to be shallow troughs.

These troughs are either delineated by clusters of hills that seem to rise above the surrounding terrain, or they are filled with darker material in some cases.

In some places, the surface appears to have fields of tiny pits etched into it. These pits may have formed due to a process called sublimation, in which ice instantly transforms from a solid to a gas, just like dry ice does on Earth.

The formation of these segments is the subject of two active scientific theories. The uneven shapes could be the result of the surface materials contracting, much like when mud dries.

They could also be the result of convection, as the wax rising in a lava lamp. Convection would happen on Pluto, driven by the meager temperature of Pluto’s interior, inside a surface layer of frozen carbon monoxide, methane, and nitrogen.

With the flyby in the rearview mirror, a decade-long journey to Pluto is over but, the science payoff is only beginning. Data from New Horizons will continue to fuel discovery for years to come.

Jim Green

A few miles-long black streaks can be seen on Pluto’s frozen plains. These streaks might have been caused by winds blowing across the frozen surface because they all appear to be pointing in the same direction.

The “heart of the heart” image, which was captured on Tuesday, reveals features as small as half a mile (1 kilometer) wide and was captured while New Horizons was 48,000 miles (77,000 kilometers) from Pluto.

In the coming year, New Horizons will retrieve higher-resolution and stereo photographs from its digital recorders and send them back to Earth. From these images, mission scientists will learn more about these enigmatic terrains.

The nitrogen-rich atmosphere of Pluto is quite extensive, as shown by observations made by the New Horizons Atmospheres team up to 1,000 miles (1,600 kilometers) above the surface. The atmosphere of Pluto has never been observed at an altitude greater than 170 miles above the planet’s surface (270 kilometers).

Tens of thousands of kilometers beyond Pluto, where the planet’s atmosphere is being stripped away by the solar wind and lost to space, the New Horizons Particles and Plasma team has found an area of cold, dense, and ionized gas.

“This is just a first tantalizing look at Pluto’s plasma environment,” said New Horizons co-investigator Fran Bagenal, University of Colorado, Boulder.

“With the flyby in the rearview mirror, a decade-long journey to Pluto is over but, the science payoff is only beginning,” said Jim Green, director of Planetary Science at NASA Headquarters in Washington. “Data from New Horizons will continue to fuel discovery for years to come.”

Alan Stern, New Horizons principal investigator from the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI), Boulder, Colorado, added, “We’ve only scratched the surface of our Pluto exploration, but it already seems clear to me that in the initial reconnaissance of the solar system, the best was saved for last.”

The NASA Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, is in charge of the organization’s New Frontiers Program, which includes New Horizons.

The New Horizons spacecraft was conceived, constructed, and is operated by the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland, which also oversees the mission for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate. SwRI is in charge of the mission’s science team, payload operations, and science planning for the encounter.