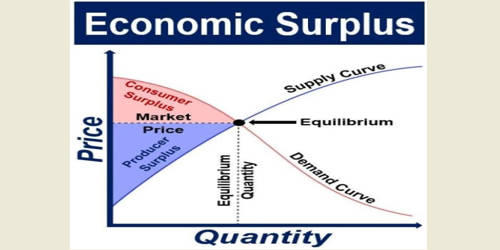

Economic surplus is the total of the producer surplus and the consumer surplus. In mainstream economics, economic surplus, also known as total welfare or Marshallian surplus, refers to two related quantities. The term economic surplus refers to the sum of producer surplus and consumer surplus. Consumer surplus or consumers’ surplus is the monetary gain obtained by consumers because they are able to purchase a product for a price that is less than the highest price that they would be willing to pay. Producer surplus or producers’ surplus is the amount that producers benefit by selling at a market price that is higher than the least that they would be willing to sell for; this is roughly equal to profit. The sum of consumer surplus and producer surplus equals the economic surplus of an economy. It is the gain that producers and consumers make when they sell or buy products.

Producer surplus: If a producer of a good is willing to sell each unit at $100, but receives $120 instead, the difference is the producer surplus. So, if the producer sells 100 units at $120 each, the total producer surplus is $2,000. ($20 X 100).

Consumer surplus: This term’s meaning is similar to that of the definition of producer surplus. But it is the surplus from the viewpoint of a consumer. If a consumer is willing to pay a maximum price of $150 for a good but can buy it for $120 instead, the consumer surplus is $30. It occurs when the consumer is willing to pay more for a given product than the current market price.

Overview

An economic surplus is the sum of all consumer and producer surpluses in an economy. In the mid-19th century, engineer Jules Dupuit first propounded the concept of economic surplus, but it was the economist Alfred Marshall who gave the concept its fame in the field of economics. Marshall explains the individual consumer’s welfare with his tool of consumer’s surplus.

On a standard supply and demand diagram, consumer surplus is the area above the equilibrium price of the good and below the demand curve. Based on the general price level and consumer expectations, consumers are willing to pay a certain price for certain goods and services. This reflects the fact that consumers would have been willing to buy a single unit of the good at a price higher than the equilibrium price, a second unit at a price below that but still above the equilibrium price, etc., yet they, in fact, pay just the equilibrium price for each unit they buy. He explains the consumer’s surplus from a given change in price as the area between the demand curve and the price axis within a range of the price variation.

Likewise, in the supply-demand diagram, producer surplus is the area below the equilibrium price but above the supply curve. This reflects the fact that producers would have been willing to supply the first unit at a price lower than the equilibrium price, the second unit at a price above that but still below the equilibrium price, etc., yet they, in fact, receive the equilibrium price for all the units they sell.