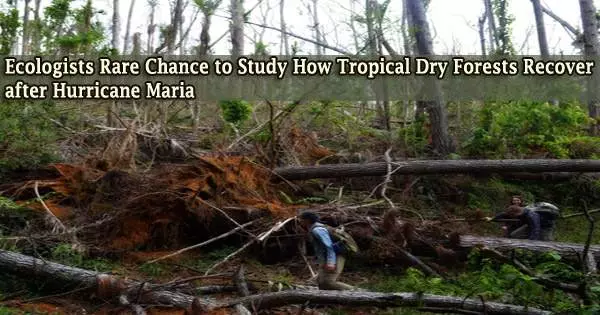

According to a year-long field study presented today at the British Ecological Society’s annual conference, trees appear to modify crucial aspects of their freshly developed leaves to counterbalance the harm hurricanes have done to their canopies.

The biggest natural disaster ever to hit the U.S. territory of Puerto Rico, Hurricane Maria, last year robbed many trees of their leaves, impairing their capacity to take in the light necessary for growth and life.

Researchers from Clemson University studied the effects of storms on the Caribbean’s tropical dry woods to determine whether trees could make up for the severe damage by enhancing resource acquisition in newly formed leaves.

In order to conduct the study, the researchers compared leaves that were gathered before Hurricane Maria with leaves that were analyzed one, eight, and twelve months afterwards for the 13 most prevalent tree species. They examined whether the sudden alterations in leaves were fleeting or persisted across several seasons.

“Our study took us to the Guánica State Forest in southwest Puerto Rico, which comprises one of the best parcels of native dry forest in the Caribbean. Rainfall here is extremely erratic, with huge variability within and between years. The forest also sits on limestone from an ancient coral reef which is extremely porous, meaning trees have little time to capture water as it travels through the underlying rock. As a result, organisms are uniquely adapted to cope with unpredictable water availability,” said Tristan Allerton, PhD candidate at Clemson University.

Many of our evergreens displayed little change in gas exchange rates and in general the relative decline in new leaf chlorophyll after Maria was much greater than for deciduous species. Under normal conditions, evergreens renew their canopies over monthly/yearly timescales, therefore it’s likely hurricane canopy damage is a more expensive process for these trees.

Tristan Allerton

Trees rely on gas exchange through their leaves, collecting atmospheric CO2 to convert into energy while also attempting to minimize water loss (leaf-gas exchange). The scientists affixed a sensor to fresh leaves in the forest at various times during the day in order to record the highest leaf-gas exchange rates by trees.

In order to efficiently extract gas from the atmosphere, newly created leaves’ shape and structure were also examined. According to preliminary findings, 11 out of 13 species investigated were absorbing CO2 at significantly increased rates right after Hurricane Maria.

Many had also altered important leaf features, such as increasing leaf area in relation to leaf biomass investment. In other words, trees used less energy to produce leaves while still being able to capture the same quantity of light.

“A key finding was that the leaves of some of the species contained less chlorophyll than prior to the hurricane. Even though new leaves were better suited structurally to capture valuable resources, lower leaf quality could reduce leaf lifespan and the trees’ ability to produce energy,” added Professor Skip Van Bloem, Allerton’s supervisor at Clemson University.

Overall, tropical dry forests in the Caribbean appear to be able to withstand strong hurricanes, while the ecologists emphasized that there might be “winners” and “losers” in terms of how different species react.

Whether dominant evergreen species can take advantage of post-hurricane conditions to the same degree as deciduous species is currently unknown.

Allerton said: “Many of our evergreens displayed little change in gas exchange rates and in general the relative decline in new leaf chlorophyll after Maria was much greater than for deciduous species. Under normal conditions, evergreens renew their canopies over monthly/yearly timescales, therefore it’s likely hurricane canopy damage is a more expensive process for these trees.”

The species composition of tropical dry forests in the Caribbean is projected to shift as a result of expected increases in hurricane frequency and severity brought on by climate change. The potential extinction of indigenous species is one issue.

“This would be a huge shame as Caribbean dry forests are known to have a higher proportion of endemic species than mainland dry forests. Many trees found there are also incredibly ancient, making these forests a living museum of biodiversity,” concluded Allerton.